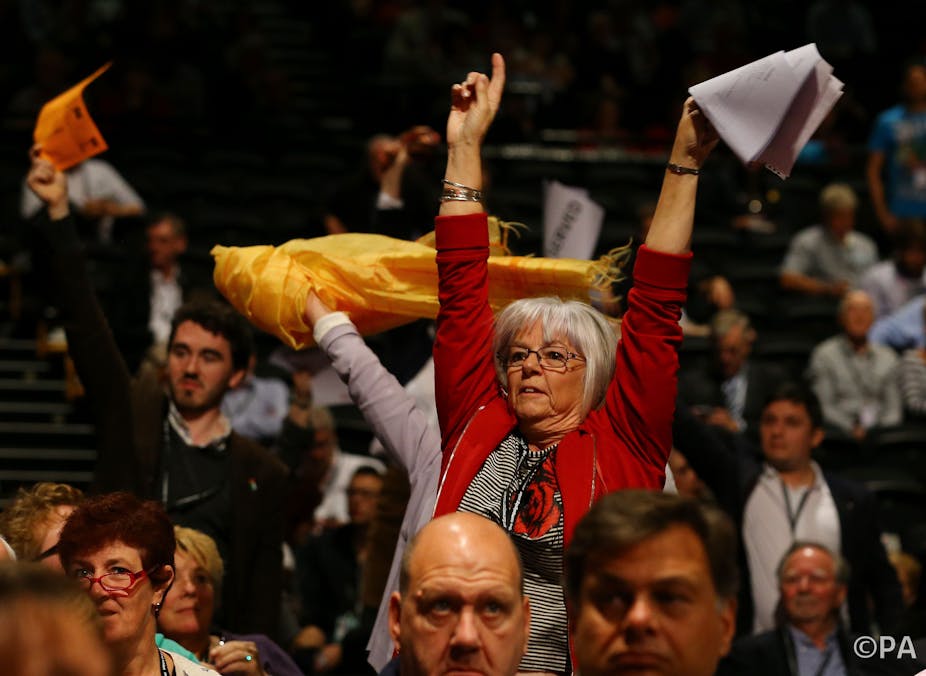

It’s all very well enthusing party members, but what about the wider public?

If any question can summarise the Labour leadership contest, this is surely a decent candidate.

For many, the two contenders in this election have had their eyes on different constituencies. Leader Jeremy Corbyn, it is said, revels in his bond with the party membership and struggles to speak beyond it. He is more concerned with denouncing austerity than addressing the aspirations of ordinary voters.

Corbyn’s challenger Owen Smith, on the other hand, is seen as aiming to connect with the larger population. They are battling to decide who the party will speak for – members first and voters second, or vice versa.

This distinction between voters and members reflects a long-term suspicion of the latter. They are typically seen as a different species from the ordinary citizen. They have their own concerns and a set of passions that others do not share – hence comparisons with religious sects.

Members’ attachment to the party tends to be presented as an identity – the expression of a personality type rather than the outcome of a reasoned decision. Voters choose, whereas members just are. Their views are an extension of their characters: well they would say that wouldn’t they?

A conscious choice

But what were members before they were members? They were ordinary citizens of course. No-one in modern Britain is born into a political party: it is a status chosen by the previously unaligned. The category is inherently elastic. A story like Labour’s, of expanding membership, is already a story about the larger population.

The habit of dividing up the electoral universe is a longstanding part of our political culture. Democracy has always tended to be accompanied by efforts to discern laws of behaviour. The idea is to divide people into separate and largely stable groups – voters, elites, members and so on – in order to chart patterns and make predictions.

Each has a distinct personality type, each their own set of attitudes. Those we attribute to the party member can be traced to a broader suspicion of political commitment. Viewed as those who stick relentlessly to their cause, members are those who stand for the intrusion of passions on civilised society. They are the kind of people who do not know how to compromise – probably mad, possibly bad.

Rising numbers

But if it was ever possible to view party members as a world unto themselves, it is unfeasible at a time when levels of membership are fluid. When large numbers are joining Labour – and in recent years also the Greens and the SNP – there can be no denying that plenty are members by choice, not identity. And given we cannot know what the ceiling to these numbers will be, and what factors genuinely limit them, we can hardly mark sharp boundaries between party members and ordinary citizens.

Nor should we want to. Even the detached observer must surely baulk at the negative way party members are being portrayed in this contest. Joining a party is one way to seek to improve society. It means taking a stand on important issues, in a measured and rule-bound way. To join a party is a classic way to exercise the rights and responsibilities of a citizen.

Rather than rising numbers, it is party decline that has been more commonly observed in recent years, in Britain and well beyond. Revealingly, when a party is abandoned by its members, this tends to be read as a valid judgement cast – a sign of the party’s irrelevance or folly. We are comfortable attributing reflection to those who leave a party: those who join one tend to be viewed more sceptically.

But as long as one is broadly committed to some notion of party democracy, the decision of individuals to join parties demands to be seen as no less reasoned than the decision of others to abstain or to leave.

Indeed, rather than see members as the oddity, perhaps it is time we saw non-aligned citizens simply as people who are yet to find their party.