After the violent attacks on Charlie Hebdo – the French satirical weekly that routinely published caricatures of Muhammad – many are wondering: are depictions of Muhammad actually forbidden in Islamic scripture? From where does this aversion to pictorial representations arise? And are all Muslims similarly offended?

Muslim opposition to pictorial representations of religious figures (or of God) does not come directly from the Quran (which doesn’t address the topic of images). But it does date to early Muslim texts that evince an antipathy toward idolatry; it also emerges from a related desire, among Muslims, to distinguish themselves from other religious communities.

Historically, many Muslims have viewed the possession of religious images as a slippery slope: a step toward worshiping idols or assigning partners to God (and thereby corrupting one’s monotheism, or shirk, in Arabic). It’s a concern Islam shares with Judaism and several forms of Protestant Christianity.

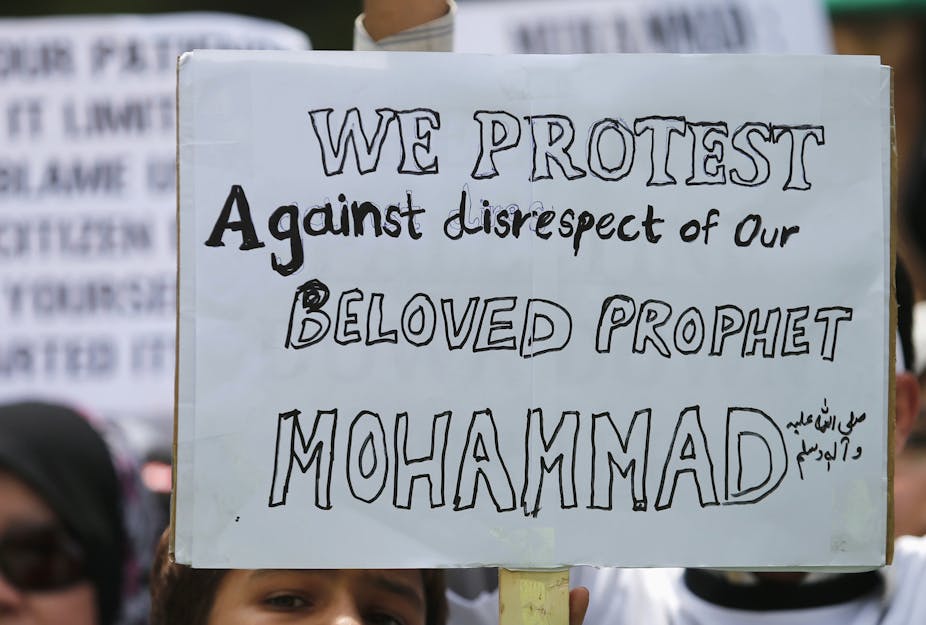

While it’s naïve to view recent violence as strictly a “reaction to images,” in the context of the culture wars that pervade our planet, images are nonetheless powerful symbols that spread quickly.

Paintings and partial taboos

Muslims haven’t always associated religious images with idolatry. There are many fine examples of painted images of Muhammad – many appear in lavishly illustrated biographies of him that date from medieval times.

Almost invariably, the rich were the sole possessors of these rare, expensive books and, as is often the case, the rules of the palace differed from those of the street. For this reason, the art and book collections of the elite probably had little influence on the religious practices of the majority, and most surviving Islamic talismans and relics in mass circulation don’t depict Muhammad or other religious figures.

Still, pictorial traditions survived in some places, while new ones emerged in others, most notably in the proliferation of colorful images of Muhammad and saints in modern Iran. Whether this can be attributed to a theological characteristic of Shi'ism – the dominant Muslim sect in Iran – or a peculiarity of Persian culture is open to debate. Outside of Shi'ism, however, predominantly Sunni societies – which, in most countries, account for the overwhelming majority of Muslims – treat religious images with an aversion verging on taboo.

But having an aversion to religious images isn’t the same as violently responding to them. Indeed, devoutly religious people often deliberately avoid subjecting their beliefs to the rough handling of the political arena. These attitudes of social quietism characterize the majority of Muslims.

To the frequent horror and chagrin of this majority, there exist Muslim individuals and groups who espouse a muscular and confrontational interpretation of their religion. They cast themselves as the moral guardians of their faith and espouse a social ideal where a singular interpretation of the religion dictates the course of private and public life. This ideology – Salafism – flourishes in an environment of conflict and disorder. It’s shared by diverse groups such as ISIS/Da’ish, Boko Haram and by the various al-Qa’ida franchises.

Such groups are always publicly opposed to any and all forms of visual representation of Muhammad – just as they are to many other aspects of Muslim life, such as visiting shrines, religious music and dance and female participation in public life. Although the Saudi state might not directly support any of these Salafi groups, it ideologically and materially sustains the politicized social agendas of Salafism. In fact, this sort of highly politicized iconoclasm has motivated Saudi Arabia to destroy cherished pieces of Islamic heritage, including artifacts associated directly with Muhammad: his wife Khadija’s house has been demolished and there are recurrent threats to erase Muhammad’s own grave.

The Prophet as American lawgiver

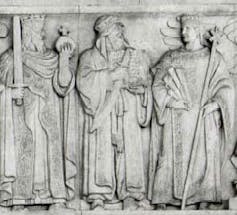

Attention given to a representation of Muhammad in the US Supreme Court is illustrative of conflicting meanings of religious images to Muslims.

On the chamber’s interior north wall, there’s a marble frieze that celebrates great lawgivers in history. Muhammad stands among them. Holding the Quran in his left hand and a scimitar in his right, he is flanked by Charmelagne and Justinian. Moses stands nearby.

Muhammad’s image went largely unnoticed for 66 years. But in early 1997, it came to the attention of Muslim groups in the US. 16 of them came together to sign a petition requesting that the face be erased. They pointed out that a 3D statue was more problematic than a painting because it mimicked the human form more closely – and, therefore, was more likely to be subjected to inappropriate veneration.

Some Muslim groups argued that it wasn’t just Muhammad who should be defaced, but Moses as well: as a prophet, he deserved the same treatment. Other objections concerned the negative connotations of the sword in Muhammad’s right hand and the placement of the Quran in his left (which is reserved for unclean tasks in Muslim cultures).

The collective Muslim reaction was respectful and thoughtful. They expressed appreciation for the intent behind including Muhammad in the frieze and suggested that some form of face veil (or sandblasting) would be enough to satisfy their concerns.

Though their demands weren’t met, the Supreme Court information sheet describing the frieze was revised to refer to Muhammad as a “prophet” rather than as the “founder” of Islam (as he’d initially been designated). It now pointedly states that the figure “…bears no resemblance to Muhammad. Muslims generally have a strong aversion to sculptured or pictured representations of their Prophet.” The matter has not been revived in the years since.

Pictures have no intrinsic value – as allowable or forbidden, likable or loathsome – to Muslims or anyone else. They matter as artifacts, and artifacts matter for their symbolic value. There may be no easy answer to the question of how and when one bows to political pressure or religious sensitivity, but one thing is for sure: as long as Muslim identity remains a contested part of regional and global conflicts, the battle over images won’t be over.