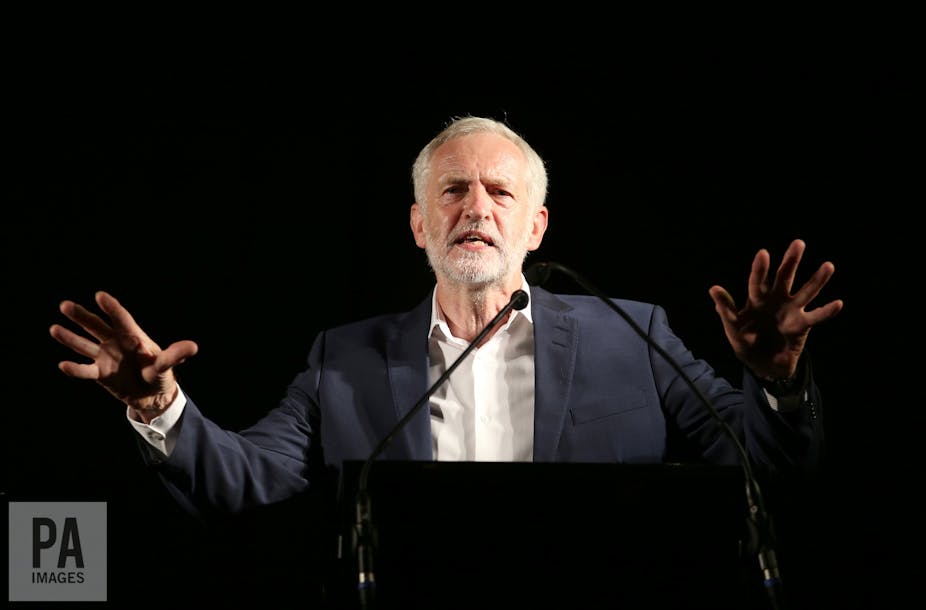

When Jeremy Corbyn floated the idea of a cap on high earnings in his first big speech of 2017, the Labour Party leader ran into hot water and quickly expanded the idea, mentioning other methods of curbing excessive pay. He emphasised the idea that excessive pay was “driving poverty pay” at the bottom of society. Nonetheless, he was widely criticised. So why is the concept of capping excessive pay such a hot potato?

The idea of having a minimum wage for workers at the bottom of the income scale has gone from being controversial to commonplace in most rich countries. And, despite the gloomy prophesying of some free market economists, there is no or little negative impact of minimum wages on employment.

Meanwhile, legislation to ensure that workers are paid a living wage – which is more than the minimum wage and based on analysis of the income needed to live a decent quality of life in a particular place such as London – is also regularly discussed. In the UK almost 3,000 employers are accredited living wage employers, ranging from big businesses to universities, unions, pubs and supermarkets. Even the payment of a basic income, where all citizens receive a basic monthly income from the government, is gaining traction and being trialled in several countries.

Inequality affects us all

If poverty was the only macroeconomic factor that mattered for people’s health and well-being then it would be enough to focus on pay at the bottom, try to raise the income floor and lift as many people as possible out of deprivation.

But in fact incomes at the top also matter. Inequality is damaging – to the economy, to society, to health and well-being and to the environment. And the evidence for this is continually expanding and becoming more robust.

Economists (including Nobel Prize winners), epidemiologists, psychologists, criminologists and sociologists contribute research, and world leading institutions, including the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Economic Forum have identified inequality as a leading problem in the world. And it is top-end inequality that continues to grow apace in countries like the UK and the US. The top 1% of earners are continuing to pull away from the rest of us, and we are back to levels of inequality not seen since the Gilded Age of the late 19th century.

Inequality’s impact is large and it affects us all, not just the poor. So if the primary role of the state is to ensure the well-being of as many people as possible in society, we urgently need to discuss pay at the top as well as at the bottom. Even Hegel, beloved philosopher of the neoliberal Right, recognised that “the livelihood, happiness, and legal status of one man is interwoven with the livelihood, happiness, and rights of all”.

Vested interests

So why such ridicule of Corbyn’s statement that he would be in favour of some kind of high earnings cap?

One reason, of course, is that most of the reactions we hear come from those with vested interests, from those on very high pay themselves. We hear from journalists, political commentators, academics, politicians and business leaders; we hear from the establishment. In fact, research in the UK and the US shows consistent and broad-based public support for reduced inequality, but we don’t hear the voices of this large majority. Just as turkeys are proverbially unlikely to vote for Christmas, the highly paid don’t like to face the fact that their incomes are part of society’s great problem.

The second reason is the deeply embedded myth that we live in a meritocracy, where high incomes reflect hard work and talent – that the rich, unlike the poor, are deserving of their wealth. Yet economist Robert Frank, in his book Success and Luck, displays the profound role of luck in successful lives. The greatest luck of all in unequal societies is having rich parents.

Then there is the idea that paying a premium for talent makes businesses and organisations perform better. But research shows this doesn’t appear to be the case. A 2003 study found that “no aspect of a company’s pay plan design predicts a company’s performance”. Another study, carried out by corporate research firm MSCI, found that companies where the CEO was paid less than the median pay within their sector performed better, in terms of shareholder value than companies with higher paid CEOs.

It’s high time for a mature conversation on high pay and top-end inequality. A variety of approaches need discussion, including employee representation on company boards, more progressive taxation, incentives for employers who cut the gap in pay, the role of pay ratios and what the research shows about what matters and what works.

Corbyn’s suggestion of an earnings cap did not come with a great amount of detail and so we do not know exactly how it would work – or whether it could be successfully implemented. But if we want to tackle inequality, we need to consider radical ideas and solutions. Instead of just dismissing or ridiculing them, we need to think more about who our economy and policy is for, and how we might all go about living happier, healthier lives.