Afghanistan has a special place in the history of international relations, having tested and endorsed many international power equations over the years. But given the imminent troop withdrawal, serious questions need to be asked about the future of the country whose destiny has always been externally determined.

Troop withdrawal

The NATO-ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) military coalition will withdraw its 87,000 combat troops by December 2014 after 13 years of fighting an insurgent war against al-Qaeda and Taliban militants.

The United States’ 60,000 troops will be halved by February 2014 and troops from the UK (7,900), Germany (4,400), Italy (2,800), Poland (1,550) and Georgia (1,550) will all pull out by the end of 2014.

Australia is withdrawing most of its 1,029 troops by the end of 2013, leaving only 400 army personnel in non-combat operations until the end of 2014 when the mission ends.

There is talk of some US troops remaining in the country as trainers and advisers, but no final agreement has been signed. If the consultative assembly of tribal elders - the loya jirga - passes the Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) between Afghanistan and the US, between 5,000 and 10,000 US troops would remain in Afghanistan to fight al-Qaeda militants and support and train the Afghan army.

This would be a big confidence booster for the local population and the Afghan security forces, although experts concede that the country needs to be better prepared if such an agreement does not occur.

Mission impossible?

The NATO-led ISAF has always declared that the Afghanistan mission was not only about fighting al-Qaeda and Taliban militants but also to assist in the reconstruction of the country by providing security to civilians and to endorse human rights.

Locals were promised that their country would be cleared of drugs and extremists, and the era of political and economic instability would end. All citizens would achieve security.

But the current situation speaks otherwise. Afghanistan still remains a large producer of drugs such as opium and cannabis; crimes against civilians and violence against women are on the rise; and the insurgency has taken a more sinister form with a combination of armed opposition groups and warlords fighting alongside the Taliban and al-Qaeda elements.

Regional instability

It is estimated that with the withdrawal of the western forces, the insurgents will be emboldened to take their war to neighbouring countries, engendering a period of regional instability in south and central Asia.

The lessons from history are plenty. Just two and a half decades ago, after successfully expelling Soviet forces from Afghanistan in 1988, the US had abandoned the country and a large number of mujahideen (radical Islam) fighters moved to the eastern border between India and Pakistan. They contributed to an unprecedented militant uprising in the Kashmir Valley, leading to tensions between India and Pakistan and the permanent militarisation of Kashmir.

India is very concerned that the absence of international forces will allow Pakistan to move its army from its western borders to the Indian side, which will inevitably escalate tensions.

Taliban threat

The opium-funded Taliban will be a bigger menace after the ISAF withdrawal. We’ve already seen opium cultivation increase rapidly in Afghanistan as ISAF deployment has decreased.

Pakistan is trying to negotiate a deal with the Pakistani Taliban and has been outraged at the timing of the assassination of Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) leader Hakimullah Mehsud in a US drone attack on November 1, 2013.

Despite the attack, America has shown a willingness to engage Taliban in peace talks, providing legitimacy and representation to the group that it has militarily resisted for so long. Afghanistan’s indigenous police and army, however, are still not prepared to face the onslaught of Taliban and other insurgent fighters.

Another problem is the forthcoming presidential elections, scheduled to take place in April 2014. The absence of current Afghan president Hamid Karzai from the election process has removed a major unifying – if controversial – figure from this process, leaving a very uncertain future for the unstable nation.

Karzai may still play a role if his kin get elected. However, the Taliban has vowed to sabotage the election process if they are held during the presence of foreign forces. It remains a very powerful and dangerous organisation and the local population is fearful of backlash.

What can we do?

This war was thrust upon Afghanistan by all sides, but it will not be any moral victory for the western forces to end militarisation without adequate investment in the capacity building of the Afghan people to deal with these challenges. This will require a comprehensive response, through international investment, goodwill and concern for the people.

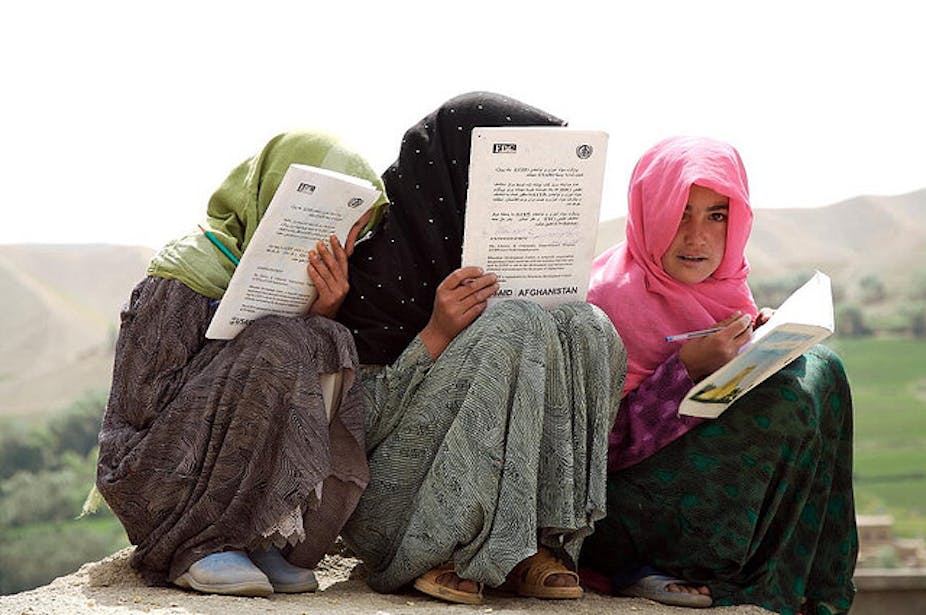

Foreign aid is essential for creating sustainable infrastructure, institutions and industrial units in the war-ravaged country and for the training, education, employment and skill development of the Afghan people.

In the longer term, Afghanistan’s transition to a stable and functioning democracy will depend on more than just external financial assistance and being a donor-dependent economy.

The locals are very sceptical about their future and prospect of peace and stability in this region. The gains made during the last 13 years – in building infrastructure, institutionalising gender equality and implementing the rule of law – may be squandered easily if the withdrawal of the troops also marks an end to any serious engagement with the country and planning for its future.