The private lives of marsupials are difficult to study. Many of them are nocturnal, very rare or overly sensitive to being put under intensive surveillance in captivity. Until now we’ve had to be satisfied with protecting the habitat of Australia’s iconic mammals and monitoring them at a distance.

But last Friday, scientists from Australia and abroad published high-resolution ultrasound images of marsupial pregnancy. For the first time, we could throw a virtual spotlight on one of nature’s most secretive events.

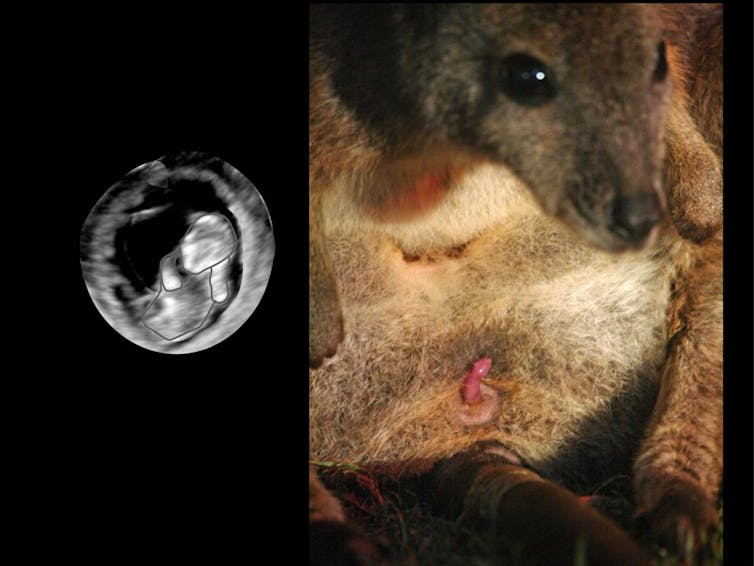

Published in Nature’s new open access journal, Scientific Reports, the study provides the first real-time footage of wallaby development in the womb. We have pictures showing its path from a tiny ball of cells to a highly active fetus that practices its climb to the pouch from day 23 of the 26 day pregnancy.

The ultrasound videos, which are also available online, show the tiny fetus repeatedly thrusting and grasping its left and right forelimbs in a coordinated effort to prepare for its unaided journey from the birth canal to the pouch.

In terms of relative developmental stage, this new footage may represent the earliest behaviour observed in any mammal. It highlights the remarkable adaptations of marsupials to navigate their way safely to their mother’s teat at such an early stage of maturation.

The study has documented several features of wallaby pregnancy that may be shared by all marsupials. These include a highly regimented developmental program, and movements of the endometrium that roll the embryo within the uterus. This latter finding is completely novel: Eutherian mammals, such as humans, don’t have uterine contractions during pregnancy as they would disturb fetal attachment. But for wallabies, these movements maximise growth of the early embryo before its short period of placental attachment.

Most importantly, ultrasound has now reached a level of sensitivity where it can be used in assisted reproduction and monitoring of threatened marsupials. With sufficient expertise, captive females could be scanned once to isolate pregnant animals. There would be no need for repeated recapture, as the birth date could be predicted from the embryo or fetus size.

In wallabies that aren’t pregnant, ultrasound could be used to check the ovaries for the presence of a “corpus luteum”: this forms after the successful release of eggs from the ovary. This could help identify reproductively active females within populations of unknown age or condition.