Deep funding cuts and uncertainty about government plans have created one of the largest-scale upheavals in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs.

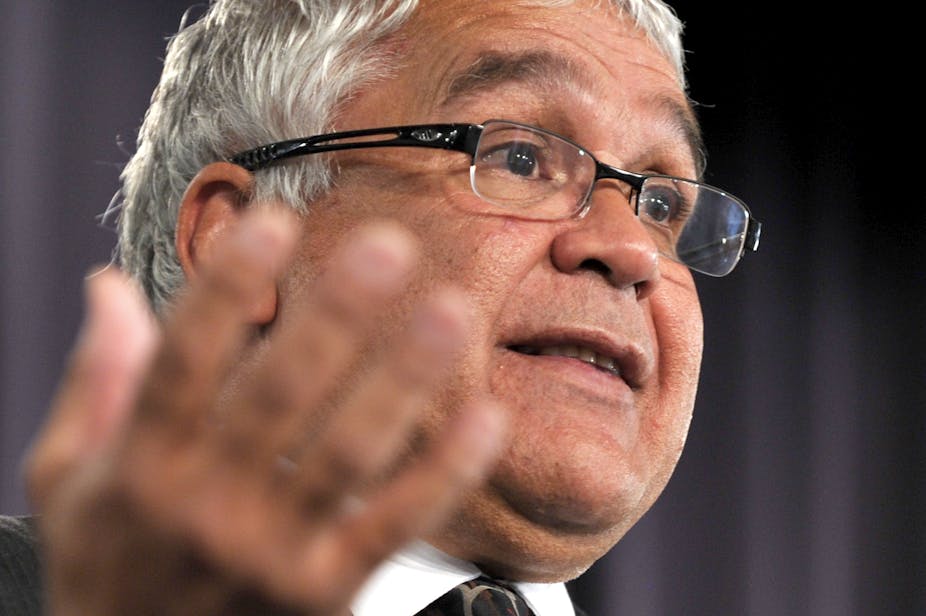

That is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Mick Gooda’s assessment in a report tabled in the federal parliament’s final sitting days of 2014. The Social Justice and Native Title Report 2014 said the changes the federal government made this year occurred without meaningful engagement with the affected communities, their leaders, or their organisations.

The inequitable status of Indigenous Australians is broadly recognised. “Closing the Gap” is an officially declared policy priority. However, the results, as recorded in the latest government report, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage, are not impressive.

The very substantial record of statistical gaps between Australia’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous people does not inspire confidence that programs and policies are working well. The latest Close the Gap – Progress and Priorities report documents some limited and slow progress, but substantial areas of regress.

Some areas, including employment, infant mortality and educational attainment, showed improvement. Movement in many other areas – such as family violence, literacy, juvenile and adult imprisonment, self-harm and child protection – was unclear, static or getting worse.

Worryingly, the statistics are indicators of broader concerns: poor health, self-harm and family problems point to widespread and deep problems.

Responses perpetuate business as usual

This pattern is not new, but the government shows no sign of seriously questioning its strategies. Despite many clues in the reports as to what may be wrong, the policy failures continue.

Why do the governments that commission these reports not heed the explanations for their findings?

There is no reason to dismiss the advice of the reports. The 2014 Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report, the sixth since 2003, is prepared by expert advisers at the highest levels of government. It notes:

The OID report is produced by the Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, which is made up of representatives of the Australian Government and all State and Territory governments, and observers from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Steering Committee is chaired by the chairman of the Productivity Commission.

There was no official interest in exploring the report’s expressed concerns about current approaches. The media response was limited to pointing out the very mixed and not-too-optimistic results. There was no investigative journalism questioning the consistently low levels of success in improving Indigenous well-being.

This lack of broader analysis and critical questioning is part of the problem. It reinforces low expectations of change and the tendency to assume that lack of progress stems from recipients’ failure to try. That explains the usual “nothing works” responses, which point out that the programs cost A$25 billion for limited benefits.

Gooda’s call to “work with us, not for us” offers a clue to the reasons for continued failures and limited successes. The OID report offers more detailed but similar indications of the need to change how decisions are taken and programs delivered.

The secret to what works and what does not is in the governance processes: the repeated failure to engage appropriately with Indigenous communities to devise and deliver policies and programs.

The OID report makes this clear. It even offers criteria for what works in a section on how programs are designed and administered. The examples of what is working, as well as what isn’t, echo earlier versions.

The common factors in programs that work

The OID report includes “things that work”. These are case studies of actions that are making a difference for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Several are drawn from the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, established by COAG and run by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) to gather information on overcoming Indigenous disadvantage.

Potential case studies were assessed against formal criteria to ensure they genuinely contribute to improved outcomes. However, formal evaluations of Indigenous programs are relatively scarce.

To provide a range of examples, the steering committee included some promising programs that have not undergone rigorous evaluation. These are clearly identified in the report.

The clearinghouse identified high-level factors that underpin successful programs:

flexibility in design and delivery so local needs and contexts are taken into account;

community involvement and engagement in program development and delivery;

trusting relationships;

a well-trained and well-resourced workforce, with an emphasis on staff retention; and

continuity and coordination of services.

These factors are closely aligned to the success factors identified in previous OID reports:

co-operative approaches between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and government — often with the non-profit and private sectors as well;

community involvement in program design and decision-making — a “bottom-up” rather than “top-down” approach;

good governance at organisation, community and government levels; and

ongoing government support, including human, financial and physical resources.

The fuller AIHW version also points out what does not work: cookie-cutter, top-down, one-size-fits-all approaches.

The evidence strongly supports these criteria for success. I have been involved in compiling examples of what works from a range of government reports on Indigenous programs. This will be published by Jumbunna Research Unit, UTS, on its website as the Journal of Indigenous Policy no. 16.

Why does government ignore its own expert advice?

So far, all the criteria in reports and websites have had little influence on polic makers: many examples of bad major policy from 2007-14 would not meet them.

This includes the so-called consultation policy around the NT Intervention and its “Stronger Futures” replacement. Programs were instituted either without consultation or after all decisions had already been made in Canberra. Despite their high costs, neither program can claim significant positive results.

Despite the Abbott government’s commitments to be more engaged in appropriate Indigenous policy, the signs so far are not good.

The processes for funding the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) have been messy. The original call for funding collapsed everything into five programs and centralised the process in ways that caused confusion. Now Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion has delayed decisions on funding for six months as the top-down design was apparently not usable, let alone effective.

Indigenous journalist Amy McQuire gives voice to the scepticism resulting from the lack of serious consultation or collaboration on planning for major changes:

The Abbott government has completely restructured the way funding is delivered in Aboriginal affairs. And the sector appears to be in complete chaos as a result. … Earlier this year, a coalition of Aboriginal organisations, led by the only nationally elected Aboriginal body, the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, slammed the IAS funding round, stating it is causing “instability, anxiety and uncertainty”.

The peak group for Indigenous-controlled children’s services, SNAICC, makes a related comment on the delayed funding and the latest Closing the Gap report in its latest online newsletter:

I suggest it is [due to] the serious gap in the knowledge of ministers and staffers and public servants who fail to learn from either the bad experiences of earlier funding or the advice of their own advisers, let alone the views of Indigenous communities and leaders.

The evidence is clear: success requires collaboration, sharing power, understanding cultural differences, plus avoiding sclerotic bureaucratic and political cultures. The unanswered question in all of this is why is it so hard to change the flawed processes of decision-making?

With no signs that future policy development will be “with, not for” Indigenous communities, maybe we need to set up a high-level inquiry into why governments fail to listen to their own very respectable advisers, let alone those who are targeted and affected.