It is 25 years since the convictions of the Birmingham Six were quashed amid dramatic scenes at the Old Bailey in London.

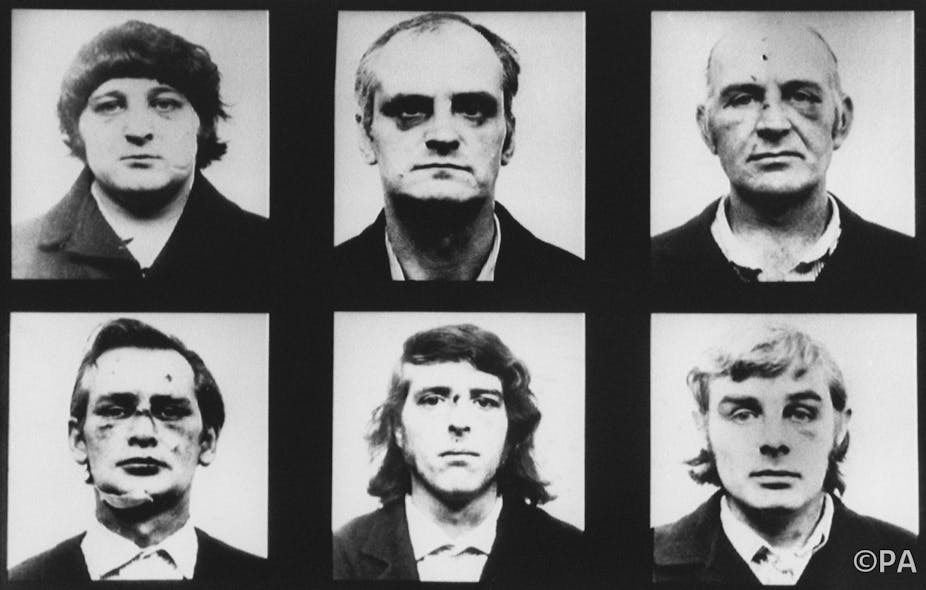

Paddy Hill, Gerry Hunter, Johnny Walker, Hugh Callaghan, Richard McIlkenny and Billy Power had spent nearly 17 years in prison for crimes they had not committed, and are widely considered to be victims of one the most notorious miscarriages of justice in British history. However, despite efforts to prevent future wrongful convictions, we find that innocent people are still at great risk of suffering perhaps the greatest injury that the state can inflict on its citizens.

When the six were released in 1991, hot on the heels of other high profile miscarriages of justice such as the Guildford Four, it was hoped that lessons would be learned so that wrongful convictions do not happen again.

The Conservative government set about a root and branch reform of the criminal justice system, and the ensuing report of the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice made several recommendations for preventing and rectifying miscarriages of justice. However, the chair of the commission, Lord Runciman, has since admitted that no attempt at reform could completely eradicate wrongful convictions.

There are a whole host of reasons why people still find themselves wrongly accused and convicted of crimes. False allegations, especially those involving sexual offences, have resulted in the wrongful imprisonment of innocent people. Prosecutorial misconduct has led to suspects giving false confessions, as in the case of Paul Blackburn.

On occasion, inadequate defence by lawyers can mean that crucial evidence is sometimes missed. Additionally, the testimony of so-called experts can sway a jury to convict, even when the evidence provided does not stand up to scrutiny. In the cases of Sally Clark and Angela Cannings, expert evidence swayed the jury to believe that they had killed their babies, but subsequent research showed that the evidence used to convict them was so methodologically flawed that their convictions were clearly unsafe.

If we can’t prevent wrongful convictions from ever happening, how do we at least ensure that people do not end up spending years, sometimes decades, in prison when they shouldn’t be there?

The Runciman Commission recommended the establishment of the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC). The Birmingham-based CCRC is an independent body with the remit of investigating possible miscarriages of justice and ensuring that appeals are submitted to the Court of Appeal swiftly. Since it began its work in 1997, the CCRC has referred 615 cases to the Court of Appeal, and of the 590 that have been heard, 404 appeals have been allowed.

In many respects, the work of the CCRC is to be commended. However, it is not the panacea for all the criminal justice system’s ills. The CCRC is inadequately funded, and lacks the resources to investigate every claim fully. In fact, their statutory remit means that they are not there to advocate on behalf of prisoners. They are charged with investigating claims, and making a decision as to whether or not there is a “real possibility” that the Court of Appeal would overturn the conviction.

This can be a real problem when we recognise that two out of three applicants to the CCRC have no legal representation, so their applications are not as rigorous as they might otherwise have been. Criminal appeals lawyers are poorly paid, with the result that many are unable or unwilling to take on cases that might sometimes run for years – especially when the bill is not settled until an appeal is finished.

In recent years, several new initiatives have been set up to assist alleged victims of miscarriages of justice put together their applications to the CCRC. Law schools across the country, including here at Birmingham, have also developed projects to investigate claims of wrongful conviction.

In 2014, Cardiff Law School’s Innocence Project oversaw the successful appeal of Dwaine George, who spent 12 years in prison for the shooting of 18-year-old Daniel Dale in Manchester before his release. Declaring the conviction “no longer safe” Sir Brian Leveson expressly praised the students who had worked so diligently on the appeal.

Earlier this year, the Centre for Criminal Appeals (CCA) received its legal aid contract, enabling it to provide legal assistance to prisoners who cannot afford the cost of a lawyer. The CCA was set up by people with experience of exonerating prisoners in the US, including those facing death sentences. Investigators and lawyers at the CCA emphasise the need for boots-on-the-ground investigation, to complement the desk-based work that has historically characterised criminal appeals work in England and Wales.

These initiatives work alongside campaigning organisations such as The Justice Gap, Inside Justice, and the numerous other groups that have been set up by family members of the incarcerated – but there is only so much that a few committed but poorly paid lawyers and investigators can do.

The 25th anniversary of the release of the Birmingham Six should act as a clarion call: there are many innocent men and women languishing in prisons in the UK, who urgently need legal representation to turn the excruciatingly slow wheels of British justice.

We cannot let a miscarriage of justice to this scale ever happen again.