I once restored a 1950s timepiece for a customer who waxed lyrical about the intricacies of my work – all the while refusing to pay. They baulked when I presented them with the bill we’d previously agreed. Then they garbled on about the philosophical nature of time, still resisting payment.

It was during that wistful, skyward narrative that I saw the timepiece slip from their hand and hit the marble floor. The mineral glass shattered, sending the hands spiralling. Sunlight streamed in from the winter setting Sun – its sharp, angular rays reminding me of how our ancient ancestors marked the passing of time.

Time was important enough to our ancestors that they went to the effort of building an extraordinary prehistoric monument, Stonehenge. The first part of this enormous solar calendar was built around 2200-2400BC.

But it is far from unique – primeval solar observatories are dotted around the world, including the Chankillo mounds in Peru (built in 200-250BC) and the Australian Aboriginal Wurdi Youang stone arrangement (age unknown). Societies around the world, thousands of miles apart, independently created sites to help mark the passing of time.

It’s in the timing

As communities developed into cities, empires and states, and societies became more segregated, time became more important and was divided into hours.

The Sumerians (4100-1750BC) based around Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) calculated that the day was approximately 24 hours and that each hour was 60 minutes long. They used the Sun, stars and water clocks to keep track of time. Water clocks used the gradual flow of water from one container to another to measure time.

The ancient Egyptians also introduced a 24-hour time system around 1550-1069BC. But the length of these “hours” varied depending on the time of year – longer in summertime than winter. These measures of time were based on the Sun, with 12 parts during daylight, and another 12 parts through the night. The Egyptians started using a sundial to represent this time system around 1000-800BC. Since sundials cannot tell the time at night, they used water clocks after dark.

In Europe, the development of time measurement gets a bit foggy over the centuries around AD700-1300AD, as all time-telling devices are bundled into the same Latin word, Horologium, in written European records.

The economist and historian David S. Landes claims in his book, Revolution in Time, that monastic Christian prayers were more rigid compared with Judaism and Islam, using the heavens to dictate what time to pray across the Catholic church’s seven set canonical hours. For example, sext was supposed to be recited at midday. The time period between these canonical prayers became equal in length because of the rigidity of prayer times.

Timepieces may also have been more important in central Europe, because the cloudier weather would have made it harder to track the Sun and stars.

Prayer time

While we can’t be certain from historical records if it was monks who made the first mechanical clocks, we do know that they first appeared in the 14th century.

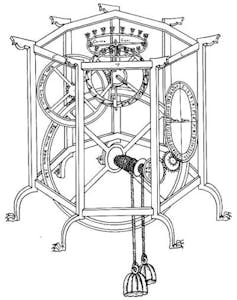

Their first mention is in the Italian physician, astronomer and mechanical engineer Giovanni de Dondi’s treatise Tractatus Astrarii, or Planetarium. De Dondi states that early clocks used gravity as their power source and were driven by weights.

These weren’t the accurate clocks we see today – they probably kept time to within 15-30 minutes a day. These early clocks started popping up in city centres but, since they did not have a face, they used bells to signal the hours. These signals began to organise the market times and administrative needs of each city.

Coiled springs as a method of releasing energy for clocks began to appear in Europe in the 15th century. This didn’t do anything to improve accuracy, but it could reduce the size of the clock. So, time became more of a personal as well as status object – you only have to look at oil paintings where subject’s watches are proudly displayed.

The Dutch scientist Christian Huygens first applied the pendulum to a clock in about 1656. This bolstered their accuracy to within 15 seconds a day, because each swing now took almost exactly the same time to complete.

As a result, time could be used more accurately in scientific observations, including of the stars. It also meant that clocks could now show an accurate minute hand.

Time tracking in other parts of the world

Elsewhere in the world, some time-tracking devices date back many centuries earlier. In the 13th century, there is evidence of the use of gears to control the movement of components in Arabic astrolabes – devices that could calculate time and help navigators determine their position. And long before that, the Ancient Greek Antikythera mechanism, regarded as the world’s first computer, is dated at around 100BC (having been discovered in AD1901). These are both devices that predicted the motions of the planets.

Meanwhile in China, there was Su Song’s astronomical clock – dated to AD1088 – which was powered by water. So, while the clock was invented in Europe in the 14th century, Arabic and Chinese societies were far more technologically advanced at this time than their western Christian counterparts.

Today, wherever we are in the world, time is a unified construct – and the search for ever-more precise measurements continues. In 2021, scientists identified a new shortest timespan, the zeptosecond, which is how long it takes for a particle of light to pass through a molecule of hydrogen.

In modern society, time is usually organised to the minute or even second (think of train timetables, how we document transactions, or record setting in sports). This internalises within ourselves an obsession with being on time. People arrange to meet a friend, and hurry to the destination when they’re a minute or too late. But really, what’s a few minutes between friends?