It is worth asking whether there are topics beyond the capacity of the novel. Are there subjects so immense in historical scope and in depths of human suffering that a form engineered to tackle but a bare handful of lives in sufficient detail cannot possibly accommodate them?

Warfare, with its punctual campaigns and political manoeuvrings, may indeed prove the limit beyond which the novel capitulates and the older form of the epic resurfaces.

And beyond that?

Review: Let Us Descend – Jesmyn Ward (Scribner)

New World slavery is beyond the ken of storytelling. As a direct corollary of that most unconscionable human catastrophe – the genocide of the Amerindians (130 million killed in 200 years) – the Atlantic slave trade is a critical component of the most important, most untellable story in the history of our species: the “conquest of the New World” by European powers.

Over 400 years, almost 13 million people were sold, shipped and bred so they could work to death on colonial plantations in South, Central and North America.

Such numbers stagger and incapacitate the imagination. Narrative, without which we fail to integrate our collective experience, is disabled by evil on this systematic scale. Slavery, as poet M. NourbeSe Philip writes, is “the story that simultaneously cannot be told, must be told, and will never be told.”

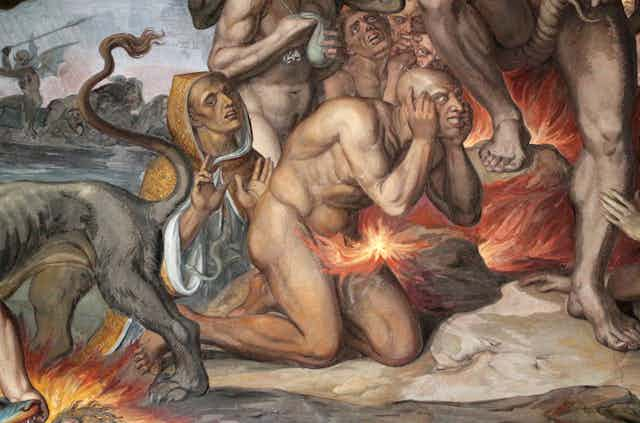

Even Dante, the greatest imagination ever to dedicate itself to the analysis and evaluation of human depravity, had no room in his packed inferno for the architects, agents and profiteers of modern chattel slavery. It is doubtful whether he could have contemplated this army of slobbering devils without immediately dropping dead in horror.

And yet they laid the foundations for our world; their legacy most powerfully shapes the present and threatens to determine the future. With no circle in hell reserved for them, their statues and namesakes are everywhere around us. They are legion.

Read more: Jean Toomer’s Cane at 100: the 'everlasting song' that defined the Harlem Renaissance

Sink to rise

Dante supplies the key to Jesmyn Ward’s fourth novel, whose title, Let Us Descend, is taken from the first Canto of the Inferno.

Ward’s pubescent narrator Annis overhears her “white” half-siblings reading Dante on a rice plantation in the Carolinas at some indeterminate date before the American Civil War. The slave girl intuits something of the greatest importance in the eavesdropped Italian vulgate: a literary guidance system for the damned – not unlike Euripides’ Medea, which becomes a lodestar in Salvage the Bones, an earlier Ward novel.

The Christian pattern of the Divine Comedy – you must sink to rise – supplies the spring and promise of this book’s dark journey: “You will rise. You will all rise.” But only if you first drown in the everlasting pain of the inferno. Here is how the spirits put it to Annis at the book’s halfway point:

Only Those Who Foretell would have known that your people who were thrown overboard, who leapt overboard, who sank to the bottom of the ocean, would become one with the deep, and after that sinking, that they would sing. Only they would know that your people’s voices would rise from the deep, that their spirits would rise like water bubbling to air in the heat of the sun.

The steep risks of Ward’s tale are all on the surface here. For this is not the language of a novel; it is cosmic, epic like Dante’s, prophetic, religious in all the most obvious senses. Yet it is obliged to cohabit a book whose narrative arc is entirely novelistic – more so than all Ward’s previous fictions.

Let Us Descend features a “Mulatto” slave girl, a predatory Sire, the banishment of her warrior Mother, a dangerous month’s journey by foot from the Carolinas to New Orleans, a lesbian love affair, sale to a sugar plantation, the trials of labour, the temptations of exile, and the ardours of escape.

Between all this earnest novelism and the increasingly ecstatic accents of spiritual affirmation, something vital goes missing.

Read more: A must-read list: The enduring contributions of African American women writers

Neglected lives

Like all Ward’s work, Let Us Descend is concerned with the neglected lives of the “other America”: the poor, the despised, the dark, those barely scraping a living on the periphery of the superstate – or in this case, the superstate’s nascent phase of accumulation.

Into her finely etched young protagonists and their blasted families, Ward breathes a tenderness that is never maudlin. She exudes a capacity for unconventional moral judgement. But now, rather than writing what she knows at first hand – present-day rural Mississippi Black folk, prey to the informal economy – Ward has projected her immense empathy onto historical material to which neither her nor her small-scale art is equal. The effects are often jarring.

Consider the enormous erudition and formal self-discipline on show in those precious few masterpieces of “slave literature” in the novel form: Toni Morrison’s Beloved and A Mercy, William Styron’s masterful ventriloquism in Confessions of Nat Turner, and Octavia E. Butler’s time-bending Kindred.

There is a discreet refusal to depict the existential inferno of day-to-day slavery directly in these works. Beloved is set slightly after the Civil War, A Mercy before the full-scale industrialisation of slavery under King Cotton. Nat Turner concerns itself with that rarest of phenomena, a full-scale slave uprising. Kindred occupies two disparate time-zones.

This discretion is matched by the rigour and authenticity of the period language, the painstaking effort to bear witness to what none of these authors (or any individual) could have seen in the round.

But the language of Let Us Descend – which, like all Ward’s novels, is narrated in the voice of a young adult – feels unmoored from history. Apart from the most obvious material referents (hatchet, lace, machete, pitchfork), it subsists in a belles-lettristic zone fenced off from socio-linguistic development.

Here, for example, is the putative voice of a pubescent, uneducated slave girl, circa early-1800s, describing her owners:

The husband’s cheeks wax round as corn cakes, red-washed with fat. He curls over her and engulfs her, eating up any shadow left in the glowing room, with his gold-threaded vest, his hair springing out over his head in big blond curls. The round pork of his shoulders fills the space. He is as showy as a robin. His wife, the small bird, flutters around him.

Who is speaking this? The first-person voice has no moral purpose if it does not make a stringent effort, in every sentence, to find the adequate linguistic material of its character’s actual situation. Instead, the voice Ward cultivates for Annis drifts off into a mellifluous if insipid drone of “style”, supplied by the author, as if to offset the character’s inadequacy as a literary instrument.

Alongside the growing vocal presence of spirits and dead ancestors, who all speak in much the same showy voice, Annis’ untethered narration nudges the fiction further and further away from all those signs of a real and inhabited American world with which Ward has peppered her novel. It mitigates the horror.

Like Holocaust stories and prison writing, the slave novel cannot long endure direct contemplation of its milieu’s actuality. As the metaphysical gradually drowns out the physical in Ward’s book, and the work of the novel is abandoned to take up the task of restituting a fraying spiritual continuity back to the west African kingdom of Dahomey, we are returned to our suspicions that the novel form is not the right one to assay this material.

The timescale of the novel form – a couple of generations at the outside and generally taking place within a few months – will not answer to 400 years of torture, unnecessary death, pointless toil and decimated hopes of millions of persons. Its formal privileging of a small company of characters gives the lie to this vast multigenerational tragedy, whose origins were misty myth by the time of Emancipation.

To be sure, every single life is a precious individual experience, worthy of discovery and artistic excavation. But before the backdrop of New World slavery, each individual is but a vanishing integer of a collective experience whose gravity, like a black hole in moral space, should sink the Americas in a cosmic ocean of shame.

Perhaps only an epic poem, like NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!, can attain the proper Dantean vantage. By not telling any story, it might allow the untellable story of slavery to leave its unholy blast shadow on the sensitive plate of language itself.