The Coalition - among others - have been recently taking aim at the worth of certain Australian Research Council (ARC)-funded projects. Verbal jousting around the value of philosophy as a humanities discipline has followed. Battlelines on these issues have formed, but as usual the truth lies somewhere in the middle. I suggest that the debate needs to mature a little.

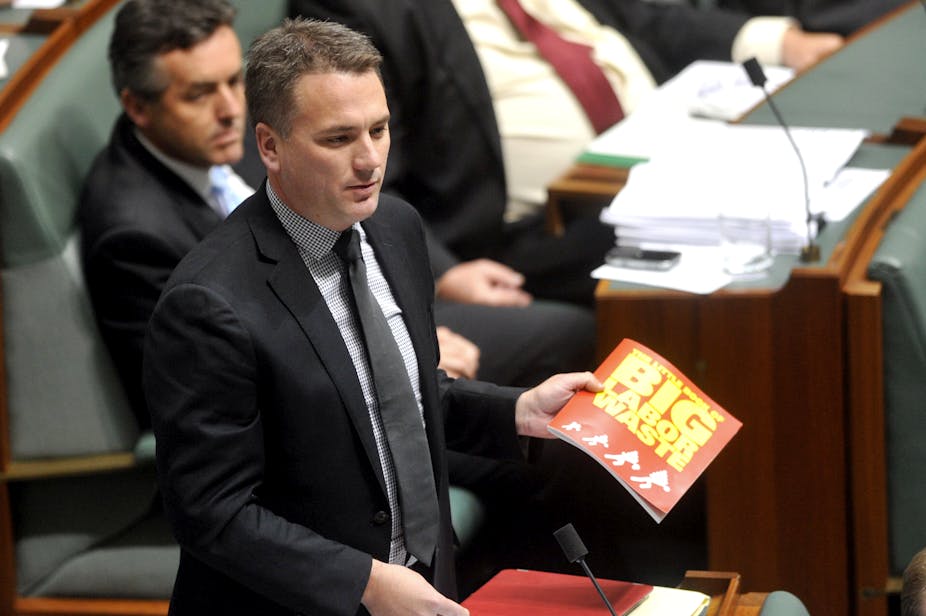

Coalition MP Jamie Briggs claims that:

We want research with Australian taxpayers’ money to be about the better future for our country, not about funding some interesting thought bubble that some academic sitting away in a university somewhere has come up with and think they might be interested in looking at.

The problem is this. Attacks on “wasteful” ARC funding tend to get conflated with attacks on philosophy itself. All philosophers do, of course, is play around with “interesting thought bubbles” in one form or another, so this is tantamount to a de facto attack on a venerable old discipline. As a result, philosophy becomes an easy target for funding waste-spotters.

Probing a little deeper, however, reveals an exquisite dilemma. A lot of philosophical thought bubbles have led to important and innovative contributions to human knowledge and civilisation over the years - more, perhaps, than some would care to admit. However, it is not always easy to spot which thought bubbles will eventually gain traction, and which ideas will go nowhere, benefit no one, and do a lot of harm (like “post-modernism”). So, as a country, should we fund philosophical research or not?

Sensibly, we try to fund some of it. A wealthy country like ours tries to scatter its resources and fund as many potentially useful ideas as it can, and uses a “panel of experts” to sort out the wheat from the chaff. Sometimes experts get it wrong, of course, and this can lead to waste. To make matters worse, committees like the ARC are perceived by some as lacking transparency and have been accused of moral deficiency. It is also not always the best people who get the money.

Some have suggested that the ARC needs to be abolished. However, as far as I know, to date no-one has come up with anything better in terms of a selection process. This leads to the perennial and recurring claims about funding “waste” and the ill-informed attacks on disciplines like philosophy.

The current process of funding the arts is imperfect, and it could be improved. But how?

I want to accept the “waste argument” (within limits), but reject the attacks on philosophy (or at least, some forms of it). There is also room for improving the process of selecting humanities research projects, so that projects in genuine need of funding might be seen to justly deserve their continued funding.

A balanced approach to funding the humanities

Like everything else, the question of whether to give funding to humanities research projects is a matter of balance. Some humanities projects do seem, at face value at least, quite wasteful and unnecessary, especially in times of resource shortage, and when there are so many deserving projects in medicine and related fields.

For example, does the country really need to spend A$325,183 on a topic about “the experiences of LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex) people in natural disasters”? LGBTI people are, after all, just people. Or $578,792 on the history of an ignored credit instrument in Florentine economic and social and religious life from 1570-1790? I have no disrespect for the researchers, or their projects, but there is a case for claiming that some projects should perhaps not be funded at all.

As a quite separate point, if it is decided that funding arts is important - and I think it is - the amounts allocated to (some) arts research funding can also sometimes seem manifestly excessive (where a much smaller amount might do). I recall the great Australian philosopher, Emeritus Professor J. J. C. Smart, telling me that he had no interest in applying for grants: all he needed to do philosophy was paper and a pencil. Having no need for funding, or a computer, didn’t stop his impressive contributions to the discipline.

Personally, I’m not that interested in credit instruments in Florentine society, let alone ones that have been ignored. So I can see why some people question why an investigation of this nature requires such an investment. I stress that I have not read the application in question, which, for all I know, might well make a persuasive case. Prima facie however, a project of this kind appears to be a case of simply needing paper, pencils and a good library. What justification could there be for such vast expense?

Even so, this should not lead to a situation of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. It does not mean all arts funding is always wasteful or excessive. Some projects are (often after the fact) so demonstrably deserving of funding, and of such “value for money”, we’d have been miserly indeed not to have spent at least some of our collective resources on a good idea when a good idea needed supporting. This is the obligation of a civilised society. The problem is how to have this intelligence in advance.

In a conciliatory spirit, let’s grant trade minister Andrew Robb’s point that, when times are tough it is reasonable to concentrate funding on areas of productivity, innovation and growth. It is also hard to disagree with historian Philippa Martyr’s assertion that funding a philosophical research project on Hegel - to the tune of $443,000 - is hard to justify when confronted with researchers on the threshold of a major advance in prostate cancer. Fair enough. As a man of a certain age I am more worried right now about my prostate than what Hegel thought.

But even so, what is considered “productive” research? And over what time scale should this research be considered? Let’s take just a few examples of philosophy’s contribution to humanity over the years.

Philosophy and its value to humankind

The sciences

Physics, chemistry and the like did not come into the world pre-formed. The philosopher Aristotle laid down the foundations of the modern-day sciences. His views were influential for hundreds of years before being debunked, after a lot of thinking, by Galileo, Newton and others (all of whom learnt much from philosophy).

No-one is quite sure how Aristotle was funded, but he’d find it hard to get an ARC grant today. How would he have justified his “interesting thought bubbles” to a committee at the time? It’s not incorrect to say that philosophy gave the world the sciences. That’s some contribution.

In recognition of this heritage, degree titles and the Chair in Physics at Oxford still refer to “Natural Philosophy”. But even now it is relevant.

Philosopher John Locke suggested that the discipline was the “under labourer” for the sciences - helping to clarify concepts and clearing the way for empirical investigation. Even now philosophers and scientists often work together on the “big” problems: consciousness, time and space, existence, the nature of numbers, and so on. In a civilised, progressive, and intelligent society this work has to go on, and it sometimes requires money (although not always a lot) to do it.

According to Daniel Dennett, philosophy is also important to science in avoiding “scientific overreach”:

The history of philosophy is the history of very tempting mistakes made by very smart people, and if you don’t learn that history you’ll make those mistakes again and again and again. One of the ignoble joys of my life is watching very smart scientists just reinvent all the second-rate philosophical ideas because they’re very tempting until you pause, take a deep breath and take them apart.

So the sciences are indebted to philosophy in a number of ways: for their genesis in the first place, and for ongoing “maintenance”.

Cognitive science and computer science

This interdisciplinary field did not come out of thin air either. It arose from philosophical speculations about the nature of mind and mental content. The logician and mathematician Alan Turing, who attended Wittgenstein’s philosophy lectures in Cambridge, was a pioneer. He left us with the blueprint for the modern computer, which was developed and extended by people who followed him. Turing’s “interesting thought bubbles” were not obviously of practical use at the time, and came out of left field whilst working on various code-breaking projects at Bletchley Park.

This philosophical work into computers and cognitive science continues, of course. Some of it has turned into very profitable businesses indeed. According to early mainframe computer maker and tycoon Max Palevsky:

…many of us early workers in computers were philosophy majors. You can imagine our surprise at being able to make rather comfortable livings.

True innovators like Palevsky, Steve Jobs and Turing are bowerbirds of philosophical ideas. They are the kind of people that may go unrecognised in their lifetimes. In Jobs’ case, he initially worked out of the family garage, took arts subjects (famously, courses in calligraphy, but also philosophy), got involved with drugs and “dropped out”. People like this don’t always have single-minded career trajectories, nor start out trying to be socially and economically “productive”. They often use their wide-ranging thinking to enormous benefit and profit only much later.

Successful countries know this, and this is why they fund the humanities - disciplines that provide ideas for those exceptional (and not so exceptional) people that might be hungry for them. Countries such as the US rarely have agonising debates about the relevance of the arts like we do.

Again, this kind of fundamental work does not always need to be given buckets of money. But it has to go on, and in a relatively wealthy society we are well placed, morally and otherwise, to fund some speculative investments in these areas. Can it be done on normal academic salaries, without the need for additional funding? I address this later.

Artificial intelligence (AI)

On a related theme, few would question the value of artificial intelligence. We have just had a visit from the world’s most realistic robot. Yet, not many would recognise the importance that philosophy plays in this area.

Closely associated with cognitive science, entire journals and conferences are now devoted to AI research. Philosophers contribute vitally to debates that clarify concepts in the field such as “representation”, “perceptual content”, “mental image”, and so on. Philosophers such as Dennett, Searle and Dreyfus are prominent here. The highly ranked journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences contains regular contributions from philosophers.

This kind of work often does need large amounts of money to keep it going. There is the potential of conducting experiments. For a variety of reasons, these experiments usually don’t come cheap. “Phantom limb” experiments and empirical work on visual perception, for example, are being conducted by philosophers interested in issues at the intersection of AI and cognitive science. Like the sciences, this needs double-blind trials, labs, equipment, and other paraphernalia.

Fuzzy logics

Logic, another invention of the polymath Aristotle, needs to be understood in its standard forms, before coming to grips with its paraconsistent and “fuzzy” variants. These logics allow scope for partial truth, where truth-values range between completely true and completely false.

This turned out to be a very important, and very practical, innovation. Once a topic only of interest to philosophers drawing funny symbols on whiteboards who muttered darkly in dusty corridors of Arts faculties, fuzzy logics now run our cars and washing machines, and much else besides.

Symbolic logic of all kinds - which would come under the category of “interesting thought bubbles” if anything did - are an invention of philosophers of various stripes down through the ages, beginning with Aristotle and continuing to the present day. The work of Carnap, Tarski, Frege and Boole is important - the latter devised “Boolean” logic which lies at the heart of the digital revolution and powers our search engines.

Linguistics

This subject did not form out of nothing either. It arose from philosophical speculation about the nature of meaning, among other influences. Chomsky, de Saussure and others all studied or contributed to philosophy. Before he went barking mad, Friedrich Nietzsche was, at 24, a professor of classical philology.

In general, philosophy has a tendency to spawn new disciplines like this - semantics, semiotics, and so on are philosophically-infused allied fields. In this sense its importance to civilisation is immeasurable. Similarly, it’s hard to estimate the value of disciplines like linguistics as a social good. And, of course, like everything else, they need money to keep them going.

Social ideas

Regardless of one’s political leanings, one would be hard-pressed to say that Marxism and Leninism haven’t had have an influence. Rightly or wrongly, this system of thinking shaped much of the 20th century. Marx himself produced a PhD thesis on the work of pre-Socratic thinker (and originator of the idea of the atom) Democritus.

Conservative thinking is also grounded in philosophy. Consider the work of Burke, Locke, Mill, Hayek, and the like, to whom our senior politicians often refer. Former prime minister John Howard calls himself a “Burkean conservative” and PM Tony Abbott apparently immersed himself in Burke’s ideas while at Oxford. Plato wrote a treatise called The Republic that still resonates and influences people today. The US Constitution is also indebted to Locke’s work, and secularism is arguably an outcome of British empiricism.

How can we estimate the value of such social ideas? Philosophy spreads fundamental ideas about both our social institutions and us as human beings. These ideas can be very powerful. Indeed, for better or worse, they help to make us the people we are. New ideas of this kind need to be encouraged and promoted (and critically assessed).

In today’s society - unlike the world of private patronage in the past - funding is sometimes needed to support their genesis and development. Again, this is where the ARC comes in.

Business innovation

It often assumed that philosophy and business don’t mix. However, recently it has been suggested that Chinese philosophy can guide business innovation in surprising ways.

In a recent TED talk, acclaimed young inventor Javier Fernandez-Han showed that the process of innovation is very similar to philosophical thinking, including the use of metaphors, similes and thought experiments. According to Fernandez-Han, what the world really needs is not the mindless “liking” and “poking” mentality of social media, but the deeper, probing kind of thinking that philosophy promotes.

While on the subject of innovation, a surprising number come from ancient Greek philosophers: the sundial, the fulcrum/lever, innovations in geometry, algebra and trigonometry, the concept of proportion and irrational numbers, a water pumping device, and one of the first military weapons, a machine for propelling stones, among many others.

Examples of philosophical invention during the so-called “modern period” include the panopticon (a prison design), and the mechanical calculator (attributed to Pascal). Is it coincidence that periods of history famous for an explosion of innovation - ancient Greece, for example, and the renaissance - were also times when the study of philosophy was taken very seriously?

How do we assess ideas like these when they are first proposed, and how do we determine which ones to fund, given limited resources?

Thought experiments

Philosophers usually don’t do physical experiments. They do thought experiments instead. Plato’s metaphor of the cave, and the notion of a deeper reality underlying and explaining our knowledge of appearances, influenced Chomsky’s notion of an innate grammar, central to linguistics.

Thinking philosophically, Einstein wondered what it would be like to ride a beam of light holding a mirror: would one see one’s reflection whilst travelling at the speed of light? This, and thought experiments like it, changed the entire paradigm of physics. These have ushered in an entirely new way of doing things, leading to countless spin-off benefits.

Adam Smith had his “invisible hand” metaphor, a concept that profoundly changed economics. John Rawls contributed the idea of the “veil of ignorance” to political science. More recently, Thomas Nagel wondered “what it is like to be a bat?” and Australian philosopher Frank Jackson speculated about a future neuroscientist who could not experience colour.

These “experiments” had an enormous impact on modern day cognitive science. Daniel Dennett recently published an entire book on “intuition pumps”, philosophical techniques that help to test our assumptions on a range of important topics.

Local ideas

Let’s not forget Australia’s contributions to philosophy. Cambridge Don Hugh Mellor once said that:

…it is well that philosophy was not an Olympic sport, for Australasia has produced more good philosophers per square head than anywhere else.

An example is Jack Smart and U. T. Place’s idea of consciousness being contingently identical to brain processes (revolutionary in the 1950s). D. M. Armstrong’s development of this thesis, and the doctrine now known as “Australian Materialism”, all of which are recognised internationally. Then there are Singer’s radical contributions to moral philosophy and the animal rights movement, and our lesser-known contributions to research on time and space, formal logic, metaphysics, and countless other fields. The comprehensive two-volume ARC-funded book - History of Philosophy in Australia and New Zealand - is due out in 2014.

Philosophy, in short, sometimes helps to push back the frontiers of innovation in surprising ways. Dense philosophical concepts are not always well-understood in advance, and it is only in hindsight are they fully appreciated. They don’t come with bells and whistles or with signs shrieking “Potential Innovative New Idea!” to funding committees.

Indeed, were a funding body to assess a project in “fuzzy” logic when the idea was first mooted it is likely the applicants would have been shown the door.

Philosophical research funding

None of the examples given above might seem as initially “valuable” as a cure for prostate cancer to be sure, but there’s no telling how important they might be in the long term. Ideas have a long currency, and they are not always immediately relevant of useful. A plausible argument might be made that curing prostate cancer is less important than good ideas. Good ideas that lead to a debunking of fixed views and which drive us, as a society, toward conceptual innovation in a variety of fields.

As it is often said, most men die with prostate cancer, not from it; a cure for it might be a luxury we don’t necessarily need. However, society really does need new ideas.

Fortunately, in wealthy countries like ours we rarely need to pick and choose. We can have healthy prostates and new ideas as well. Powerful ideas that have real applications can come from the most unlikely sources, and are often recognised as such only retrospectively.

Sometimes these great ideas arise in the normal course of doing philosophical “business”. Sometimes they are an appropriate and integral aspect of routine professional labours. Occasionally, however, they require funding to make the ideas fly. How do we, as a society, determine which ones to back?

Suppose a modern-day Alan Turing turns up to a funding committee, cap in hand, asking for money for his idea to develop a modern-day equivalent of his theory of a “Turing Machine” (he didn’t call it that, but that’s how it has since become known). He has no evidence for its usefulness or potential value. He doesn’t even know what it might possibly be good for.

Turing is planning to produce his (now famous) short paper for a philosophy journal, Mind, as a “performance indicator” in return for the funding from the public purse. He’s asking for several thousand dollars, mainly to fund research and development work for this idea, and to relieve him from a heavy university teaching load. Should the funding committee give him the money?

It’s likely that hard-nosed critics of the ARC would refuse his application and give him his marching orders. There is likely to be little recognition that this apparently simple little idea would, in time, spawn the digital revolution—arguably the most important revolution of the 20th century, which we are still feeling the effects of today. This idea would change everything, from medicine, to communications, literacy, and commerce. Nothing would be the same after it:

The fact remains that everyone who taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program, is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine.

I am not suggesting that there is no wasteful spending in Arts funding. Clearly there is. I get as annoyed as others do when I see my taxes going to fund projects that, in my view, seem to have little obvious merit. However, I’d be prepared to admit my ignorance, and would be reluctant to dismiss such projects without having read the proposals in detail. My point is that over-the-top attacks on humanities funding simpliciter stands in need of a corrective.

Attacks on the purported extravagant use of public funds for humanities research should not be tantamount to disparaging the disciplines from whence they come - especially in the case of philosophy.

Reconsidering funding models

Here’s a positive suggestion for the funding of philosophical research, and humanities scholarship in general: greatly widen the selection and assessment requirements. I propose that all arts funding should be internationally assessed and funded by the collective, pooled resources of a global body set up for this purpose. Call it, for the sake of the argument, “The International Humanities Research Council”.

Perhaps the assessors on the council - not all of whom need be “experts”, but intelligent and interested parties - might be circulated regularly and often. A key rule might be that representatives from a country have to leave the room when a funding application from their own country is assessed. This way, there may be less likelihood of “cliques” occurring, and less chance of any coteries forming for the purpose of mutual backslapping.

There might also be less chance of the “Matthew Effect”, whereby academics who have been successful in getting grants tend to get more.

Once grant applications are “over the line” in terms of being deemed (in principle) worthy of funding, representatives from each country might then make “bids” for particular projects on the “open marketplace” of the council floor. Let’s imagine that all the applications for future humanities funding go into an international pool with our competitive neighbours who share our democratic ideals (US, UK, Japan, and so on). In principle, it need not be so restricted, for the humanities are important to us all.

Let’s also imagine that whoever funds the idea - whoever wins the “bid” - gets any benefits that might ensue. It’s winner takes all. The ideas themselves might be developed in Australia, but their benefits, if any, would go offshore if that’s where they are funded.

“The International Humanities Research Council”

What might happen in such a scenario? I’d expect that the naturally less risk adverse countries with bigger pockets (the US, for example) would take greater risks, and potentially obtain the greater yields from esoteric “blue-sky” ideas.

Countries with a penchant for florid prose, and post-modernist speculations (like France), might back projects with which it had broad philosophical sympathies. They would be welcome to them in my view.

Nations where philanthropists have a strong involvement in funding decisions might support esoteric topics of broad cultural and intellectual appeal (like the “History of the Emotions”). It’s a personal preference of course, but I can see how this kind of thing might be interesting and culturally enriching, even if it didn’t result in economic-spin offs. Not all innovations have to be measured in such terms.

Australia has a much lower budget, a degree of intolerance toward the humanities, and prefers to waste public money on large sporting events (which is rarely questioned). Such a country would benefit only from work that is deemed to be immediately and practically “useful” in some sense. They might miss out on benefiting from the really important ideas - such as Turing’s - that eventually garner a great deal of traction and lead to untold economic, technological and/or social advantages.

Historically, Australian innovations tend to be developed and profited from off-shore anyway, so perhaps we are used to this and it would be nothing new. The point is that through global comparisons, and bidding competition, we would quickly know which countries had a genuine interest in promoting humanities research and which didn’t. It would become clear which countries genuinely cared about the arts, and their place in a mature society.

In this scenario, international specialisations in the humanities might occur. This may not be a bad thing. Japan is already well-known as being pre-eminent in the applications of fuzzy logic to industry, known as the “fuzzy boom”. This localisation of humanities research might continue apace. With specialisation comes efficiency, and greater economic gains.

The outcomes of such a proposal also might be that international humanities research turns out to be funded quite well overall; perhaps better than at present, and there would be a diversity and spread of opinions with which to assess the value of the projects. Of course, ideas that appealed to no one would understandably fail to receive funding and would wither and die - as perhaps they should.

If nothing else, if implemented, this suggestion might stop the negative harping about “wasteful” government spending in the arts.

Does philosophical research need additional funding?

Like any discipline, philosophy is only as healthy as the funding it receives. And, like any other discipline, philosophy needs to pursue new avenues to stay fresh. Sometimes, but not always, this requires additional contributions from the public purse by means of ARC grants.

Can this be done without additional funding from the government? Unfortunately, the fact is that the routine business of merely being employed in a humanities faculty these days is insufficient for philosophical labours - Smart’s point about just needing “paper and pencil” notwithstanding.

This is especially the case in the cash-strapped, bureaucratically bloated, managerial tertiary sector that exists today. This perilous situation has been noted in more than one paper. Contrary to popular belief, academics are not well paid compared to politicians and business executives—though, admittedly, they are relatively well paid compared to academics in some other countries (who are paid poorly, so this does not say very much).

A 2009 study showed that academic salaries declined against average weekly earnings and a range of other professions. Being an academic in the tertiary sector today means being burdened with “administrivia” and having little time for research while being on average salary.

When funding is slashed across the tertiary sector, the first thing to go is usually support for the Arts and disciplines like philosophy. This results in a loss of staff and higher teaching loads. When academics do apply for money from funding bodies such as the ARC - and sadly, academics are now de facto revenue raisers for the institutions that employ them - it is invariably to fund research assistants, teaching relief, and the like.

The majority of money from humanities funding ends up in salaries for support staff and time-release. A lot of this is “on costs” for our cash-strapped universities to fund building maintenance and the like. This explains the seemingly exorbitant projects mentioned earlier. Applying for funding for these expenses are necessary evils in the contemporary tertiary environment if academics are to have hope of finding time to think and write about anything at all.

A different approach

A much more radical suggestion than the International Humanities Research Council - or perhaps something to consider in line with it - is giving grants for promising ideas without requiring academics to apply for them. This counterintuitive suggestion has been arrived at from a summary of several empirical studies that looked at the negative costs to productivity of applying for grant applications.

There are a number of points in its favour. Firstly, scientists in Australia spent the equivalent of five centuries preparing research grant proposals in 2012. As only 20.5 percent of applications were effective this means four centuries of wasted effort. As humanities researchers are demonstrably less successful in obtaining grants than scientists, this presumably means even greater waste.

Secondly, in a Canadian study it was found that the CAD$40,000 cost of preparing for a grant, and being rejected, exceeded the cost of giving all qualified investigators an average baseline grant of CAD$30,000.

Thirdly, net returns on grants are lower than if they were given at random.

A number of alternative suggestions are considered in response to this: giving grants to everyone who requests them; allocating grants randomly; allocating on the basis of past track record; funding research on the basis only of an abstract.

I would not be partial to giving grants to everyone even if it could be afforded, for reasons mentioned earlier. There are limits to what is worth funding; and yes, among the many excellent proposals that are funded, there is probably some unnecessary waste.

However, something does need to be done to mitigate the waste of applying for grants. This seems an equally, if not more pressing, problem than the purported “waste” of some humanities research projects.

The practicality of philosophy

This article is a partial response to those who are negatively judgemental about philosophical research, and who are intent on shamelessly bashing the humanities. I want to suggest these attitudes are frequently (if not always) misinformed.

These negative attitudes are particularly galling for humanities academics as they often formed rashly without having done the courteous thing of reading the ARC grant applications on which such projects are based, or only on the basis of reading the title and the 100-word summary.

Is it too much to ask for those critical of ARC grants to provide evidence that they have done due diligence and actually read the applications? Making assertions about waste is fair enough: making judgemental, uninformed assertions is poor form. I am particularly keen to defend philosophy, since examples from this discipline are so often unfairly held up to ridicule.

In funding philosophical research, we are, in effect, funding an oft-neglected, “poor cousin” discipline. This discipline has real practical outcomes for individuals and society as a whole, quite independently of the innovations and contributions to civilisation that it might provide.

Continually questioning funding for philosophy is false economics. This is so for a number of reasons, but the practical reasons are perhaps most surprising. As absurd as it may seem, philosophy is, in fact, one of the best subjects for students to study to get good grades. A 2011-12 survey of GRE scores by the Educational Testing Service noted that philosophy was the best major in terms of developing verbal and analytical writing skills, and among the top five in developing quantitative skills.

In the US, the discipline is recognised as being one of the most demanding, and over there at least, philosophy enrolments are soaring. As the US is a dynamic, innovative country that we frequently like to compare ourselves to, perhaps we should take notice. They may see something in the value of the arts that we don’t.

Unexpectedly, philosophy one of the best subjects for employability. Studies have shown that, while starting salaries of philosophy graduates might be less than those with business degrees, by mid-career, the salaries of philosophy graduates surpass those of marketing, communications, accounting and business management. And it is probably not necessary to mention the many examples of famous or successful people who majored in philosophy, and who turned into business or finance pioneers.

The list is surprisingly long, and includes people one would least expect - financier George Soros and Paypal founder Peter Thiel, for example. Those who had “soft” college majors in other humanities disciplines also fare well (locally, the multimillionaire founder of “Jim’s Mowing”, Jim Penman, is a historian). Others have claimed unambiguously that business needs philosophy — an exhortation which runs against the grain of those who think the discipline is excessively funded.

It should be noted that the proportion of ARC funding that is directed towards humanities research is usually vastly overstated. In fact, it is abysmally low compared to funding directed toward the sciences. According to former ccience minister Kim Carr, the ratio was typically 80% to the sciences and 10% to the humanities. I am not suggesting at all that this balance is inappropriate. It seems fair and reasonable, as the sciences do require a greater share of government funding. I do, however, object to suggestions that the Arts receive an inflated share.

Why does it matter?

Does it really matter if the ARC, or our universities, fund and underwrite the occasional obscure research project in humanities? Are things so tight that we cannot speculate on things that do not have an immediate practical application?

Some of those esoteric ideas will have real traction and make a difference. Others won’t. This is the nature of taking a punt. But this is no different from other areas, for example, putting money into Olympic swimming teams, horse racing carnivals, or backing research for space exploration — and this funding is rarely questioned. My grandfather, a committed SP bookmaker in his day, used to say that all that racing ever produced was horseshit.

To be sure, Hegel’s may not seem so germane these days, but - not being a specialist in the area - I would not bet on it without knowing more about it. I certainly would not rely on Brigg’s or Robb’s untutored opi nion of projects such as these. Personally, I’d need to read the project proposal myself before jumping to conclusions, and they should too.

Perhaps an argument might fairly be made that a project on Hegel, for example, has been excessively funded, and some of it is best directed elsewhere. In some cases this might be a fair point to make. However, this is a slightly different matter. This would warrant a detailed discussion about project budget items (usually rigorously dissected by the ARC). This does not warrant Brigg’s and others’ condescending comments about the “interesting thought bubbles” often pursued by academics.

In other words, it’s time for a little more subtlety in the discussion. The propositions: “All humanities research is wasteful” and “All humanities research is necessary” has been in opposition for a long time, and it is a tired and stale debate.

But in any case, benchmarking research on Hegel with path-breaking work on prostate cancer is more than a little unfair. Surely, a rich country such as ours has enough to go around. Though it is important to have some standards too: I draw the line at funding “postmodernist” views, for reasons I can’t go into.

But more to the point, where else would idle philosophical speculation be done if it were not done in our universities? With Australia’s poor record in philanthropy, I can’t see BHP or Rio Tinto putting their hands up to fund esoteric humanities research (Twiggy Forrest’s latest gift aside). This can only be done in our tertiary institutions. Arguably, that’s what they are there for.

One of the problems in this debate is that specialists in the humanities partly have themselves to blame. They often fail to sell themselves and the value of their work to the general public. They are not encouraged to be good at public engagement. This is partly a function of the peer-reviewed and competitive nature of the tertiary sector, and the degree of self-absorption that most areas of intellectual enquiry entail. It has much to do with the excessive managerialism in universities today.

It is also a function of lack of experience.

If philosophers were more akin to business people, and were required to make a “pitch” for their idea in simple, unambiguous language before their funding masters, or if the assessment process was broadened internationally as I have described, this might be better for all concerned. The recurring debate about “waste” in the humanities might dry up, or at least be placed on a more intelligent footing. A good thing all-round.

Philosopher John Armstrong puts the problem like this:

Fundamental and blue-sky research … is possible on a large scale only with the profound consent of a whole society. And universities—which are the natural homes of intellectual ambition—are not organised to secure this consent. Those who are fired by the love of knowledge do not see securing such support as fundamental to what they do.

Yet, if we are to carry off the huge task of gaining such committed and widespread support we would have to devote ourselves to a vast project of engagement. We would have to have this task written into the DNA of research culture. And this is the fateful irony.

We want the support that requires a great public but we don’t want to do the things that would win the loyalty of a great public. At worst, we want to demonise the philistines and have their taxes pay for our noble enthusiasms.

Fair enough, I say.

In conclusion

But in the end, providing a small amount of public money for funding research into the humanities is not about curing cancer, getting a job or making money.

It is about you. Suppose in your dotage you suddenly acquired a passionate interest in the use of bird imagery in Shakespeare’s sonnets. Perhaps you become fascinated by an obscure lemma of substructural logics, or wanted to know all about the theories of a long-forgotten Polish aesthetician. Where, in the panoply of human endeavour, would you go to satisfy your yearning for knowledge?

Naturally, you would go a university library, or a reputable website or journal. This is where one will find the published work of scholars in the humanities. Unfortunately, this work does not come out of thin air. Nor is it free.

Phillipa Martyr’s “test” of whether humanities researchers would fund their research from their own pockets is as absurd as suggesting that physicists buy their own oscilloscopes. The sad thing is, on Brigg’s, Robb’s and Martyr’s economic rationalist thinking, this important research would dry up completely.

It would, indeed, be a farewell to Arts. We’d have healthy prostates but that’s about it.

Humanities research, whether immediately practical or not, is rightly funded from the public purse, and should always be so. It is a measure of our cultural maturity to provide such funding in an intelligent, thoughtful, and measured way, but it also makes good social and economic sense. Long may it continue.