Journalists have never been particularly fond of advertising or advertisers – to most journalists, advertising was space and time taken away from good stories and advertisers were commercial interests trying to bribe or subvert them. Ironically, now journalists are wishing there were more advertisers with deep pockets – and so are media proprietors, as they watch their audiences and share prices tumble.

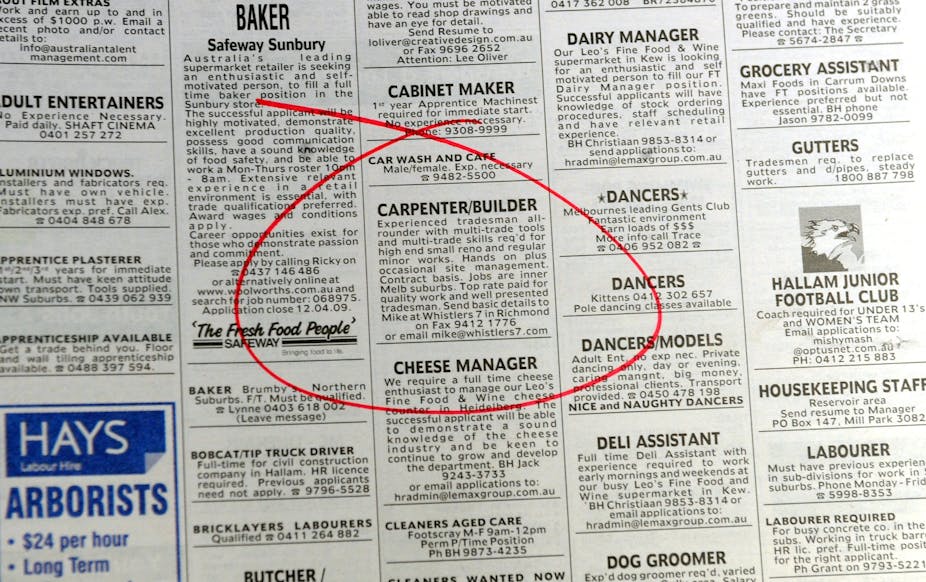

Not only have the “rivers of gold” that flowed from classified ads dried up, but print display and broadcast advertising volume and rates are falling, as mass audiences fragment into myriad micro-audiences and grazing information consumers roaming the internet.

Some observers and commentators cannot resist the “I told you so” reaction, as warning signs of transformative change in media production and consumption have been evident for some time. Rupert Murdoch admitted in a speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors in New York in 2005 that he and his massive media empire were slow to recognise the importance of the internet. In the 2009 A.N. Smith Memorial Lecture in Journalism, managing director of the ABC, Mark Scott said “We have reached a point that we should perhaps have seen was coming, yet largely we did not”.

But pointing fingers and 20-20 hindsight are of no more use than the head-in-the-sand approach of the 1990s and early 2000s. The multi-billion question now is “what business model can sustain commercial media in future”? Not only is that question on the minds of media proprietors and shareholders, but the careers of many journalists and quality journalism – long recognised as integral to a healthy democracy – are also on the line, as they have long been dependent on their love-hate relationship with advertising.

So, what will be the business model of commercial media in future?

“She’ll be right – it’s just an adjustment”

One thing for sure is that things won’t right themselves. Media belong to an industry undergoing major structural change. While reducing costs is a necessary step, even Fairfax’s recent slashing of 1,900 jobs over the next three years and closure of two printing plants will not solve the problems that traditional media organisations face. A 2009 PriceWaterhouseCoopers study noted that newspaper publishers have responded to economic downturn by focusing on cost reduction. But the PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PWC) report titled Moving into Multiple Business Models: Outlook for Newspaper Publishing in the Digital Age concluded that “many have still to fully review their existing business models to take full advantage of the innovation in the marketplace and the demands of consumers”.

Advertising 2.0

A second key fact that needs to be recognised is that, despite all the crisis talk, advertising is still a major revenue stream for commercial media. While down compared with the “golden age” of mass media, advertising is likely to remain at least part of commercial media business models for some time to come.

Furthermore, advertising is evolving, particularly online. After some rather crude first steps with banners stuck across the top of Web pages and annoying “pop ups” that blocked viewing of content, new forms of advertising include rich media (advertising involving video, sound and even animation as well as graphics) that can be embedded in “newspapers” online; interactive advertising; user-generated advertising; and expanded product placement (including Photoshopping of branded products into existing media content).

The evolution of Web 3.0, the Semantic Web, will see further significant developments in advertising. Search engines will increasingly be replaced by “recommendation engines” which capture users’ profile data and clickstreams to target them with relevant advertising (referred to in the trade as “behavioural targeting”). Privacy advocates and some social scientists are concerned about these developments, but they offer benefits to advertisers and some consumers may even welcome them, as they reduce exposure to irrelevant content.

Charging for content – the push for paywalls

The gorilla in the room, potentially huge but unpredictable and even dangerous, is charging for content. This business model began in earnest in January 2010 when the publisher of the New York Times, Arthur Sulzberger Jr announced that America’s most prestigious newspaper would start charging for some content from January 2011. Rupert Murdoch announced that News Corporation would progressively introduce charges for accessing the content of its titles worldwide.

News Corporation’s Wall Street Journal began charging for content in 1996 and the UK’s Financial Times and the Australian Financial Review also have charged for content for some time. However, sceptics argue that this model has worked for business and financial media, but question whether media consumers will pay to access general content. At best, only premium content can be put behind a paywall, according to many analysts and industry leaders. They base this view on the experiences of a number of US, UK and New Zealand titles that have implemented paywalls, only to see circulation plummet even further as audiences turned to free internet content.

In Australia and the UK, the challenge is even greater because of the presence of substantial publicly-funded media such as the ABC and BBC which do not and most likely never will charge for content. In his A. N. Smith Memorial Lecture in Journalism in 2009, Mark Scott said that commercial media paywalls in the UK and Australia may simply drive up traffic to the BBC and ABC.

Studies by PriceWaterhouseCoopers and the Boston Consulting Group suggest that paywalls will increasingly be part of the business model for commercial media, but that they will work only for some in-demand and specialist content. Also, research indicates that paywalls may only generate micro-payments rather than the “rivers of gold” of the past. Head of the Boston Consulting Group media group, John Rose, said the BCG study found “consumers are willing to pay for meaningful content. The bad news is that they are not willing to pay much”.

Other potential business models discussed and advocated include:

Public funding which already applies to some media such as the ABC and which some academics argue should be expanded to sustain quality journalism. However, economic pressures on government and competing demands such as health and education funding make this unlikely;

Sales commissions in which media take a percentage on sales of advertised products, including through classifieds, rather than simply charging for space and time. Major consulting firms such as Deloitte, KPMG and PWC have recommended this model for some time, but the horse may already have bolted now that vast quantities of advertising of properties, cars, consumer products and jobs have shifted from newspapers to sites such as eBay, Craiglist and Gumtree;

Diversification into consumer products. This has already been done to some extent with books (e.g. good food, dining, gardening and home decorating guides), directories and DVDs, but consumer products marketing could extend to mobile phone services (such as exclusive ringtones from popular programs and photos of its major stars as screen savers); food products, wine, clothing labels, luggage and holidays;

Archive reuse and repurposing. KPMG has identified “potentially huge” business opportunities in media archives which include billions of articles, reports, photos, reels of film, sound files, and historical accounts of important events which could be re-used and re-purposed for research, corporate art, “reality” footage for the movie industry, and even fashion and home decoration;

The “attention economy” – a radical concept proposed by business analyst Michael Goldhaber and also advocated by internet aficionados Alex Iskold and Richard MacManus in which advertisers pay citizens a small amount each time to give attention to their ads. Consumer attention is valuable, so advertisers should pay for it, rather than simply handing over their money to the media, is the argument behind this concept;

Endowments, a philanthropic system common in the US, although not in Australia;

Foundation grants, also common in the US, but again not widely practised in Australia;

Establishment of media as not-for-profit entities; and

Creation of hyperlocal Web sites and blogs.

What will be the business model that saves our media and quality journalism? I don’t have a crystal ball, but research shows that all of these, and some other approaches, offer opportunities, but none offers a panacea. Therefore, the most likely scenario for the future will be a hybrid, a diversified approach. Diversification has always been a wise business strategy and perhaps the lack of it has been the problem all along.