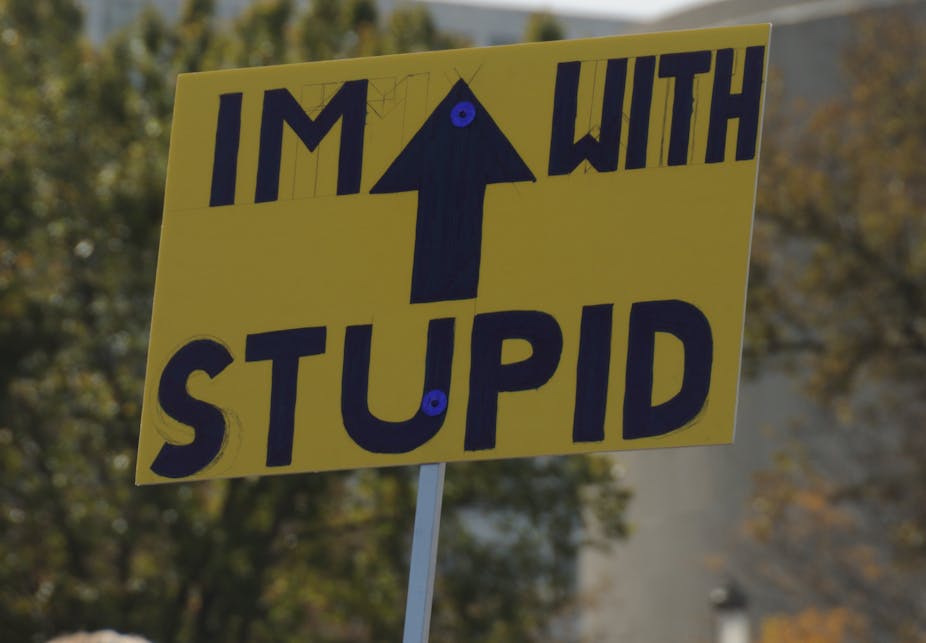

For a brief period of time in the 1980s, one of the biggest selling t-shirts carried a print of an arrow which simply said “I’m with stupid”. It pointed to the person next to the witty wearer.

In the 1990s, the arrow rotated 90 degrees and pointed to the wearer’s crotch. The gag here was clearly that our t-shirt wearing comic was led into all sorts of misdemeanors by their sex drive. Sadly, clothing entrepreneurs of recent years did not update this classic design and have the arrow pointing upwards to the wearer’s head, as the real stupid person is often ourselves.

The t-shirts of the late twentieth century might tell us a little about how we have thought about stupidity, and how it gets us into trouble. Initially, we assumed stupidity was somehow inflicted on us by other people – who were of course much more dim-witted than us. Then, we began to think about stupidity as springing from our animal urges to compete and to procreate.

But the increasingly common wisdom today is that our propensity for stupidity comes from the very way we think about and react to the world. It has also profoundly informed how we think about the great disasters that routinely appear in our hallowed institutions.

One particularly neat case of this is the role of stupidity in the apparently never ending banking crisis which began in 2007. For some, the crisis was caused by the stupid people beside us who had worked their way into powerful positions in the large banks and had gone on to make some disastrous investment decisions. For others, the financial crisis was driven by the testosterone fuelled culture of investment banking getting out of control.

The real reason for the crisis in the banking sector was our own stupidity – the stupidity of relatively rational, reasonable and functional people.

This is the central insight that lies at the heart of the eagerly awaited report released by the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards. The document highlights a series of problems which beset the banking sector, ranging from poor regulation to a lack of women on the trading floor.

At the centre of all these problems is the creeping insight that many of the people working in the banking sector were not idiots (on the contrary, it employs many of the best minds in the country). Nor were they only pumped up city boys (although a few were). Rather, these were on the whole ordinary and decent people who turned off part of their capacity for rational and critical thinking when they went into work.

According to the report, the great rationality switch-off in the banking sector happened for a range of reasons. There were skewed rewards systems that led people to think about short-term gain rather than long-term benefits. A lack of personal responsibility which allowed people to get away with reckless behaviour. An over-reliance on complex financial technologies and systems cloaked in fancy business school jargon. There was a lack of space to voice criticism about irrational and immoral behaviour in the bank. And there were not enough regulators actually holding bankers to account, and asking them to rethink their behaviour.

All these factors created a toxic cocktail of what my colleague Mats Alvesson and I have called functional stupidity. The ability to get the job done by switching off your critical thinking abilities.

What is surprising about the Commission’s report is that it recommends some fairly serious medicine to cure this epidemic of functional stupidity. It suggests that bankers are more clearly held to account as individuals – and when they break the rules of the game they should be personally punished. Instead of a golden handshake, they would receive a stint in jail.

It suggests a fundamental change in the way people are rewarded in the banks, with a greater emphasis on longer term performance rather than short-term gain. The way banks are governed should also change. This involves having greater independent oversight within the bank, and strengthened risk management functions. The role of this would be to ask tough questions within the bank.

The report also recommends that it be made easier for people to speak out if they see something going wrong. This should be supported by better whistleblowing procedures. The regulators should also be strengthened – with the ability to not only look at technical issues like capital ratios, but to also examine a bank’s culture and business processes where they appear to be a cause for concern.

If enacted, all these measures would be a significant step towards rooting out the systems which have supported stupidity among otherwise reasonable people in the banking sector. What remains to be seen is whether our politicians have the will to begin implementing these much needed changes, and whether the banks have the vision and the stamina to do the hard work necessary to make these changes happen.