A sniper, a black man, situates himself by an upper-floor window overlooking a street filled with white police officers busy overseeing a protest march. He proceeds to shoot and kill as many of them as possible from his vantage point with a high-powered rifle, before the police deploy an even more powerful weapon to retaliate and end his killing spree.

This may sound like a description of recent events in Dallas, Texas, during which Micah Johnson, an Afro-American US Army reserve veteran, enraged by the stream of recent police killings of black people, shot at white police officers from the Dallas Police Department, killing five and wounding seven.

But in fact these events are taken from Chester Himes’s novel Plan B, which he started writing in the late 1960s and which was finally published posthumously, unfinished, in France in 1983, and not in the US until 1993. What the novel and the events in Dallas force us to face is the fact that race relations in the US are as much a flashpoint today as decades ago, and that if police keep killing black people then they will be likely to face more organised resistance, and the state’s monopoly on legitimate violence will be lost.

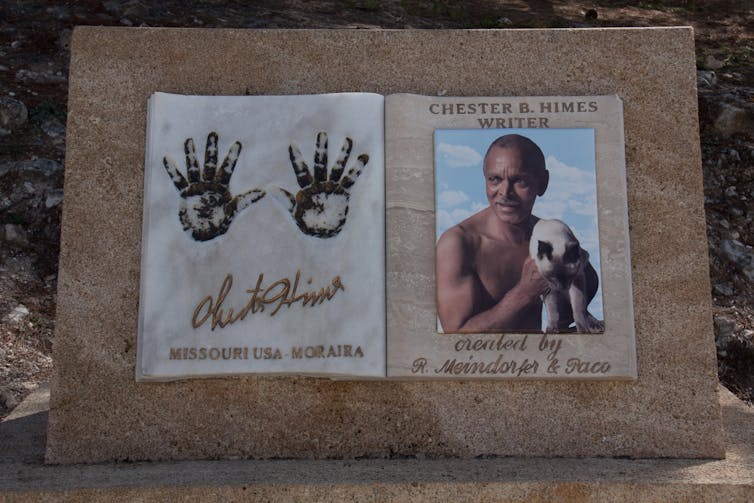

Himes began his career as a protest novelist but turned to crime fiction following his move to Paris in the mid-1950s. There he wrote his Harlem Domestic series, about black police detectives “Coffin” Ed Johnson and “Grave Digger” Jones and their struggles, in vain, to bring order to Harlem.

By the time Himes began Plan B he had grown tired of depicting scenes of disorganised violence, and increasingly struggled with the task of reconciling his detectives to the demands of upholding racist laws.

With Plan B, he envisages what a violent black uprising might look like and what its consequences would be. In the novel the knockabout brutalities of his two detectives are replaced with acts of straightforward political intent. “If there must be violence,” Himes declared, “I believe it should be organised violence”.

Even in its own time – an era marked by race riots throughout the US – there was something uncomfortable about the dead-eyed precision of Himes’s depiction of black organised violence.

Today, 50 years later, the violence unleashed upon young black men and women by the police that has lead to deaths in Missouri, New York, Maryland and Louisiana to name but a few, would doubtless not have surprised Himes. Nor perhaps would the actions of Johnson.

Indeed, what Himes’s prescient novel shows us is that race relations and racial antipathies have not changed much and that racially entrenched violence has a long history – one subplot takes us back to the era of slavery. Here though, we should pay special attention to the consequences of the sniper’s act.

In Himes’s novel, the felling of white policemen is met by a disproportionately aggressive response on the part of the authorities, and many more black men and women are killed. This in turn compels new instances of black violence and the situation soon descends into all-out civil war: black men “running amok and shooting white people right, left, and center” and demands from the white population that “all blacks be locked up in [prison]”.

Now and then

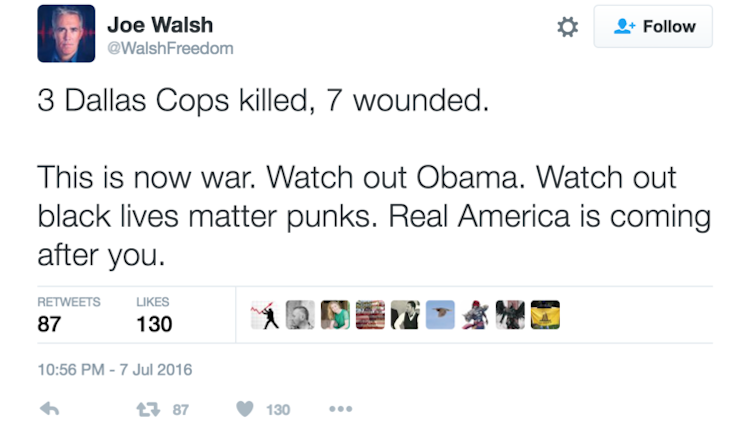

It would be scaremongering to suggest that this scenario is even a remote possibility in 2016. But what if we situate the Dallas sniper’s actions, as Himes would, within a long continuum of racially-inflected violence – a continuum that includes the police killings of black men like Michael Brown in Ferguson? What if we also pay attention to responses to the Dallas shootings by (white) men like former Republican Congressman Joe Walsh who tweeted: “This is now war … Watch out black lives matter punks. Real America is coming after you”?

For Himes, who believed in the political potential of writing “to be a force in the world” but who worried that literature “couldn’t change anything”, the logical end point of his terrifying vision is racial Armageddon. It’s hard to know how literally we are meant to take this vision, but Himes was so uncomfortable about his conclusions that he couldn’t finish the novel.

The consequences for Himes’s writing career would be far-reaching – once Pandora’s box is opened, not even his detectives could put things back together. In the unfinished part of the manuscript he set out plans for Grave Digger to kill Coffin Ed, an act Himes described as “literary suicide”.

It is worth thinking about the nihilism of Himes’s novel and what it suggests for our present. If Plan B tells us anything, it’s that we shouldn’t be surprised by what happened in Dallas. Also, by paying closer attention to figures such as Himes and confronting the terrible conclusions he reaches, we can endeavour to actually understand the nature of entrenched racial divisions, then and now.