There can be no more powerful symbol of the relationship between Australia and Papua New Guinea than the prime ministers of these neighbouring countries walking together on the gruelling Kokoda Track towards Isurava, high in PNG’s rugged Owen Stanley mountains.

The place where Anthony Albanese and James Marape chose to commemorate ANZAC Day was the scene of one of the toughest battles in the Pacific war, the Battle of Isurava. This is where raw Australian conscripts and militiamen fought back against an invading Japanese force in August 1942 until veteran reinforcements arrived. Their combined efforts inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese and, crucially, slowed their advance.

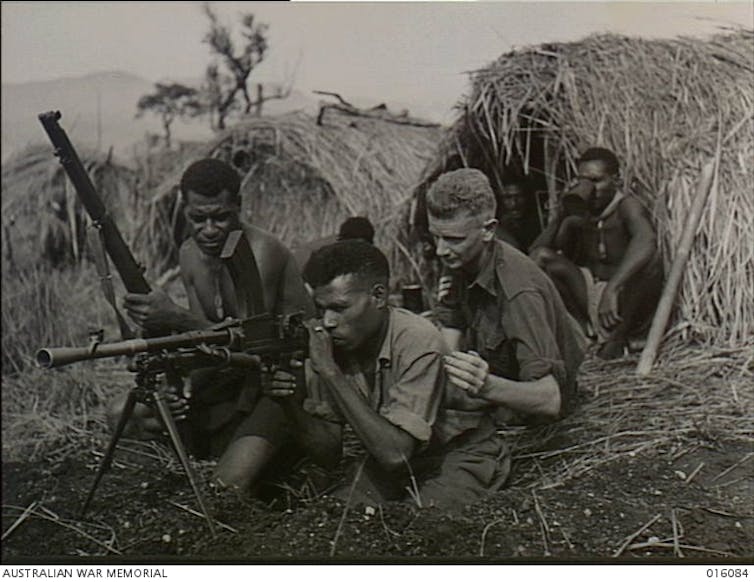

The Australians were supported throughout this and many other battles on the track by Papua New Guineans – the stretcher bearers who carried the wounded back to safety and the soldiers of the Papuan Infantry Battalion.

This moving collaboration has become the reference point for generations of leaders from both sides of the Torres Strait when speaking of the special relationship between the two countries. It has also inspired many Australian individuals and organisations to “give back” to PNG through financial donations and other support.

How history informs Australia’s view of PNG

The events of 1942 had a lasting impact on Australian strategic thinking about its neighbourhood.

During the war, Australia’s lifeline to the United States across the Pacific was under direct threat from Japan’s sweep across the region. The military objective of the Japanese forces on the Kokoda Track was the capital, Port Moresby, because of its utility as a base for ongoing attacks against Australian ships and cities. For a while, an invasion of Australia itself seemed to be imminent.

The protection of Australian lines of supply and communication across the Pacific remains a central consideration in contemporary strategic thinking.

Australia’s deep sensitivity to any suggestion a potentially hostile power may be seeking to establish a naval base in the region actually predates the second world war. However, the very real threat that materialised on the Kokoda Track entrenched this view.

PNG still looms large in Australian deliberations about regional security – given its size, this wartime history and its proximity to Australia and pivotal location where Asia meets the Pacific.

Of course, it is no longer Japan that Western strategists see as the principal strategic adversary and potential threat to stability in the Pacific. That mantle has been assumed by China, which in recent years has displayed an active interest in expanding its military links and presence in the region.

Japan has now become an important strategic ally for Australia and the United States in working to counter China’s growing influence in the Pacific, including PNG. It has made important contributions to the region’s development through aid and other economic support.

Papua New Guineans naturally have their own understanding of history, as well as today’s security environment. As Marape said last week in response to a gaffe by US President Joe Biden about his uncle having possibly been eaten by cannibals after being shot down during the second world war,

World War II was not the doing of my people. However, they were needlessly dragged into a conflict that was not their doing.

China’s ambitions in the region

As in other parts of the Pacific, there is no enthusiasm at all in PNG about the re-emergence of geo-strategic competition in the region. PNG leaders have joined their Pacific counterparts in emphasising climate change as the key regional security challenge and criticising their international partners for stoking tensions with China.

At the same time, there is an underlying lack of enthusiasm in PNG about expanding the country’s ties with China to include defence or policing ties.

The Marape government came under real pressure from Beijing to sign agreements covering police training and other security co-operation in the lead-up to Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Port Moresby last week. Ultimately, it did not do so.

Marape and his ministers have made it clear they look to Australia – not China – as their country’s key security partner.

China may have ambitions to establish a security partnership with PNG similar to the one it has signed with Solomon Islands, but it clearly has no interest in matching Australia as a development partner for the country.

Its aid spending in PNG – as in the rest of the Pacific – is very minor in comparison to Australia and may be in decline. Beijing has shown in Solomon Islands, at least, that it prefers to focus its money on nurturing relationships with members of the ruling elite.

However, China has made significant inroads as a commercial partner for PNG. Its construction firms now dominate the work taking place across the country to develop roads, bridges, public buildings and other infrastructure.

But China cannot match the breadth of the PNG relationship with Australia. This relationship encompasses social, cultural and sporting ties, as well as longstanding investment, aid and defence co-operation links.

Read more: What do people in the Pacific really think of China? It's more nuanced than you may imagine

‘History holds all the details’

Kokoda may have become a kind of public talisman for the Australia-PNG relationship, but there is much more to the two countries’ shared history than the wartime experience, as Marape made clear in his speech to the Australian parliament in February.

To make this point, he highlighted the presence in the parliamentary gallery of elderly former Australian patrol officers and their families who had dedicated their lives to the early development and administration of his country. He spoke with gratitude about the period during which Australia administered PNG – and with pride about the years since independence.

History holds all the details, for the greatest and most profound impact of the Australian administration is the democracy you left with us.

It was clear from this speech he believes Australians underestimate the depth of their own historical ties with PNG. Australians should take some comfort, in these uncertain strategic times, from the ballast these shared experiences provide for the relationship today.