Twitter made hay this week as Facebook suffered what has been described, perhaps a tad hyperbollically, as “the longest outage in recent memory”. That’s if your memory doesn’t stretch back much further than four years – when the last major outage happened.

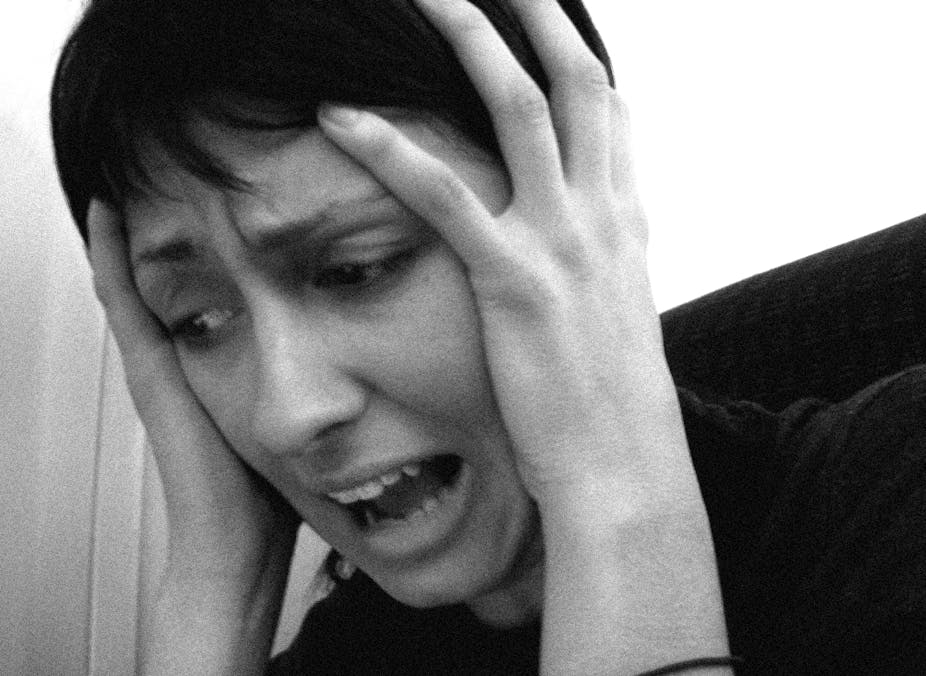

The biggest social networking site in the world went down for 20 agonising minutes on June 19, leaving users frantic. Some were reduced to sending their morning selfie to contacts via text message and others reported forgetting what all their friends’ babies looked like. Some may even have sent password reminder requests to MySpace.

My favourite tweet came from stoic social media user @SimonThomsen:

“Where were you in the Great Facebook Crash of 2014, dad?” “On Twitter son, but I Instagramed about it”

What brought the world to the edge of panic for 20 minutes? We don’t know yet and we shouldn’t really speculate without evidence but let’s give it a go anyway.

Meanwhile, in Ireland

On the morning of Wednesday, June 18 2014, Mr Justice Hogan gave his ruling in an Irish High Court hearing that saw the government accused of failing to investigate Facebook International – which is based in Ireland – for transferring data about its customers to the US National Security Agency.

Could there be a connection between this tricky case and the outage that shocked the world just one day later?

It’s no secret that US politicians and the media think the European Court of Justice has been getting a bit uppity about privacy in recent months. In April, it annulled the data retention directive and in May, it told Google to respect a limited right to be forgotten, specifically relating to name searches. In both cases, the court ruled the fundamental right to privacy, guaranteed by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, was being undermined.

With killjoys ruining the NSA’s fun in Europe, maybe it took drastic action after Hogan’s ruling and decided to do an emergency back up before the European court could lock all that lovely Facebook data away. Maybe some newbie spy accidentally blew a Facebook fuse in the process.

OK, fine. This isn’t really what happened but there is a serious point here. Facebook is a large corporation controlling a wealth of personal information on an unimaginable scale. When it goes down, we suddenly think about what we might have lost.

For many, Facebook is the internet. It’s where their digital identity resides. What do they do if it goes down and never comes back? What do they lose?

Yet they don’t seem to think about what they lose when Facebook hands that personal data over to the NSA, or to any other security or intelligence authorities, such as GCHQ in the UK.

Max Schrems, the Austrian activist who took the matter to Hogan’s court, was thinking about it. Hogan, for his part, said there was a serious case to answer. The good judge suggested that the Irish Constitution would effectively block Facebook from handing personal data to the NSA except for the fact that a European Commission privacy Safe Harbour decision from 2000 bypassed those protections.

The Safe Harbour scheme effectively enables the transfer of EU citizen data to the US. Justice Hogan’s decision amounts to a serious critique of technology giants’ facilitation of mass and undifferentiated surveillance by state authorities, particularly those in the US.

He’s now offering the ECJ another opportunity to lay down some rules on this surveillance. Specifically he wants a review of whether the Safe Harbour decision is still defensible in light of not only what we know about the NSA but also the new privacy rights introduced in the EU in 2009. Of course these protections won’t do much for you if you willingly post all your most personal information on a social media site that will then take ownership of it. If you broke out in a 20-minute sweat this week, perhaps its time you did a back up. Or just ask the NSA if they’ve got any of your messages.