What is a human body? This may seem a facetious question, but the answer will be very different according to which medical tradition you consult. Take Ayurveda, a traditional system of medical knowledge from India which has enjoyed a renaissance of popularity in the West since the 1980s – and is the subject of a new exhibition at London’s Wellcome Collection.

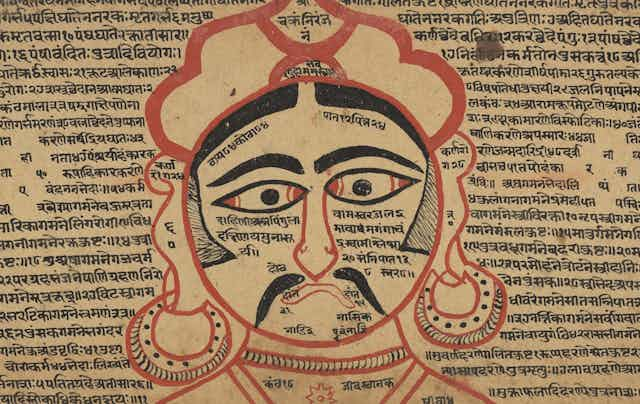

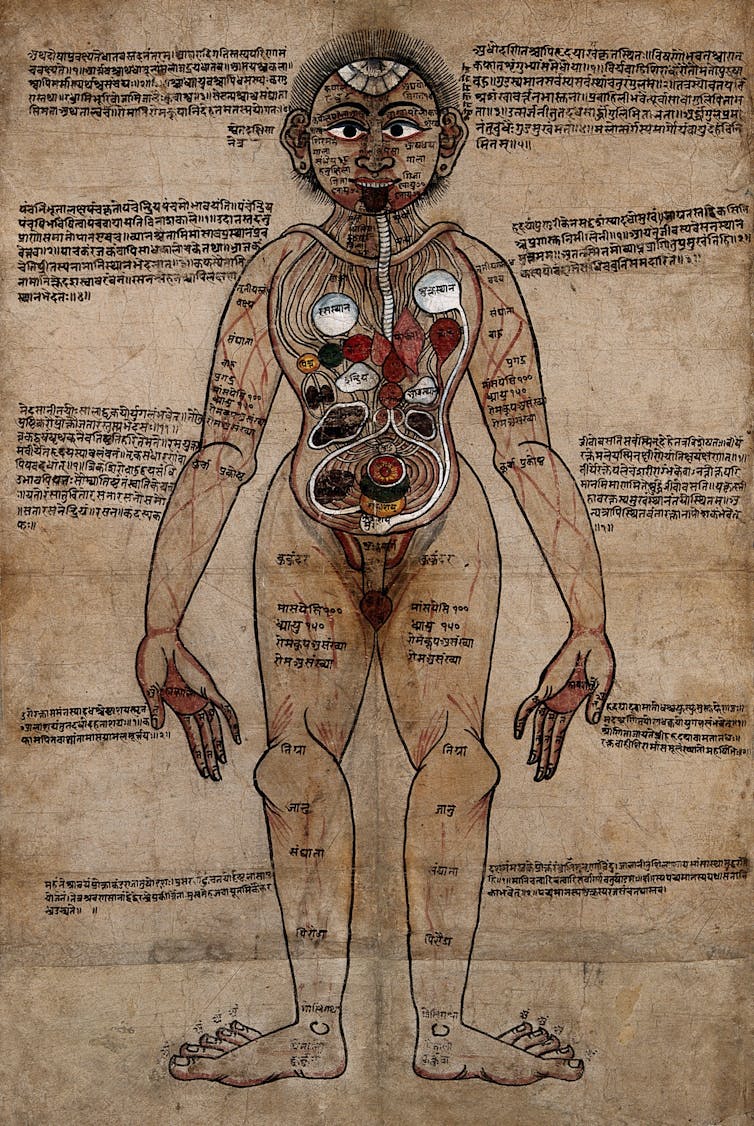

Walking round the show, one is encouraged to explore different ways of understanding and visualising the human body. The Ayurvedic body differs significantly from that of European biomedicine, which is based on dissection. The Ayurvedic body is a body of systems. It is conceptualised as being composed of five constituent parts (mahābūta), seven body substances (dhātu) and three regulating qualities (doṣa). According to Ayurvedic theory, by attending to imbalances between these principles in a body, health might be promoted and illness avoided. The Ayurvedic concepts of the doṣas – vata, pitta and kapha can be seen in the West today promoting teas, soaps and massages.

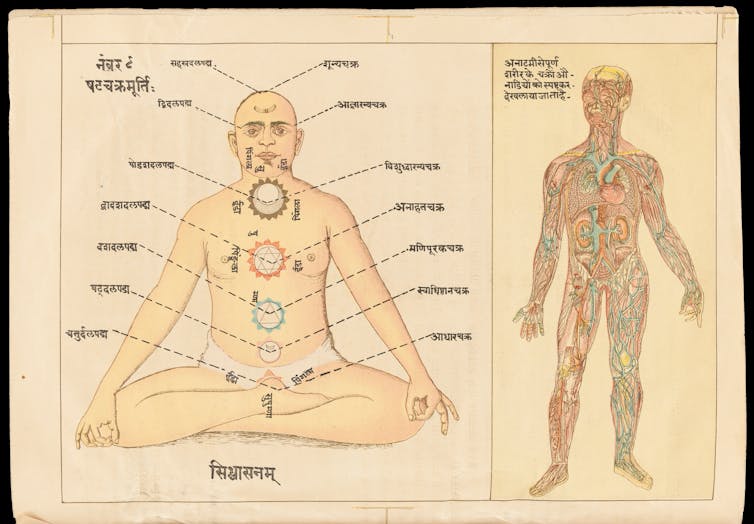

But of course, there are many other different conceptions of the human body. There is the tantric understanding, often conflated with that of Ayurveda. Tantra focuses on the concept of energy channels (nāḍīs) which have particular centres of concentration along a line in the centre of the body (chakras). The traditional Chinese model, on the other hand, emphasises the dynamic principles of ying and yang as being paramount for ensuring health. Meanwhile, indigenous healing in many traditional cultures identifies problems between the individual and the greater social and metaphysical context as the cause of illness.

Competing medical systems

So what, then, has determined the dominance of one medical system of thought over another? The answer is far more complex than the “correct” or “most accurate” one.

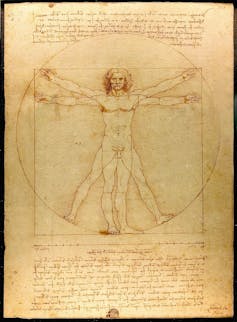

This complexity is epitomised by the central piece of the exhibition, one of very few illustrations of the classical Ayurvedic systemic descriptions of the human body. This 16th-century drawing, as Dominik Wujastyk’s research has shown, was probably produced at the request of a rich, Nepalese patron by a scholar-physician, a scribe and a painter, none of whom were fluent with the original Sanskrit source. The Nepalese artist was clearly influenced by Tibetan medical illustrations.

We don’t know how this image was originally used or how influential it was, but its creation was dependent upon patronage and intercultural exchange. It was out of this mix of cultures, then, that came one of the most iconic visual presentations of the “Indian” Ayurvedic body.

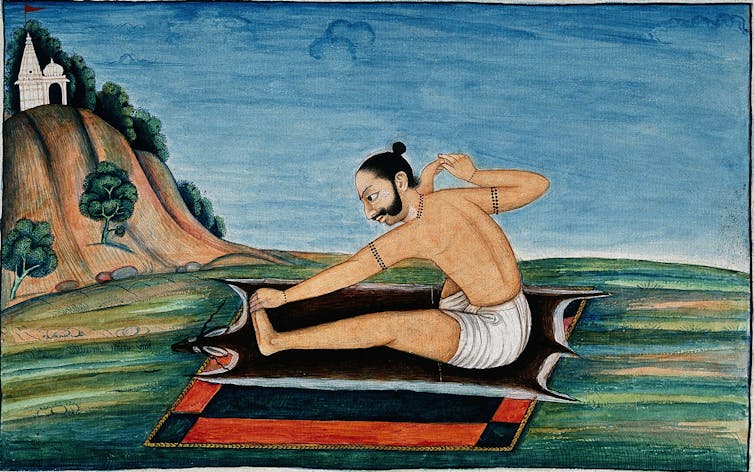

Economic and political powers are strong influences on the shape and popularity of Indian concepts of the body today. Yoga is currently the most widespread Indian approach to promoting the health of the body. It is flourishing globally. Millions attest that yoga makes them feel better and Ayurvedic concepts are often presented as integral to yoga practices.

But it is not well known that the contemporary global interest in Ayurveda and yoga is partially a result of colonial mismanagement of India. This point is creatively illustrated in the Wellcome’s new show through an interactive commission by the artist Ranjit Kandalgaonkar. Millions of lives were lost throughout the colonial period due to forcible redistribution of food and other resources away from local Indian populations, to serve what were considered to be the greater needs of the British Empire.

As I have argued elsewhere, reactions to the tragic deaths of millions of Indians transformed yoga. Swami Vivekananda was inspired by the effects of famine and plague to redefine Karma Yoga as a social-service mission. Many leaders of the Indian independence movement, including Mahatmas Gandhi and Mohan Malaviya, promoted Indian approaches to medicine and health.

And so the establishment of the modern Indian nation was closely linked with the health of millions of individual Indian bodies through “Indian” systems of healing. This continues today as the prime minister Narendra Modi demonstrates through his association with Indian’s popular “yoga-televangelist” Swami Ramdev and the elevation of traditional medicine to that of an independent government department.

The promotion and preservation of Indian medicinal knowledge is laudable. But it is important not to oversimplify complex and sophisticated descriptions rooted in different worldviews. Economic imperatives often flatten traditions into marketable exports – and intercultural exchanges both enrich and confuse our models of understanding.

Many understandings

So should there be one answer, one dominant understanding of the body? I’m currently part of a team researching the overlaps between yoga, Ayurvedic medicine and Indian longevity practices (rasāyana) over the past 1000 years. Our research emphasises a plurality of understandings through time. Both yoga and Ayurveda are characterised by a diversity of practices, as well as by internal conceptual coherency. Millennia of intercultural exchange has created problems for asserting national ownership of traditional medical knowledge.

All medical systems have shared interests in promoting human health and longevity. But it is important to understand the differences as well as the similarities. As early as 1923, Indian commentators were expressing concern about the potential biomedical “mining” of traditional remedies for single active ingredients. One commentator in the Usman Report, a pan-Indian survey of over 200 indigenous medical practitioners, asks: “Does this amount to quackery” by biomedical physicians?

Today, our mental image of our bodies is largely picture built up from dissection and, more recently, x-rays and various other scans. Yet in practice, we understand our bodies as a changing system. We monitor our energy levels. We adjust how we feel with food, drink, sleep, exercise and drugs. The Ayurvedic, system-oriented body, then, is perhaps not that far from most people’s daily experience. So how might we better visualise our bodies based on our lived, somatic understandings?

Ayurveda is a rich and complex tradition that has always encompassed influences from a variety of cultures as well as retaining very specific, local applications. Ayurveda cannot be reduced to a simple definition, marketing slogan or quantifiable national export. The Wellcome’s new show explores these complicated relationships and raises important questions. If we are not to become “quacks” ourselves, we must continue to resist reductions of the human body into a single visual model.