This month marks 40 years since NASA launched the two Voyager space probes on their mission to explore the outer planets of our Solar System, and Australia has been helping the US space agency keep track of the probes at every step of their epic journey.

CSIRO operates NASA’s tracking station in Canberra, a set of four radio telescopes, or dishes, known as the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (CDSCC).

It’s one of three tracking stations spaced around the globe, which form the Deep Space Network. The other two are at Goldstone, in California, and Madrid, in Spain.

Between them they provide NASA, and other space exploration agencies, with continuous, two-way radio communication coverage to every part of the Solar System.

Read more: Water, water, everywhere in our Solar system but what does that mean for life?

Four decades on and the Australian tracking station is now the only one with the right equipment and position to be able to communicate with both of the probes as they continue to push back the boundaries of deep space exploration.

The launch of Voyagers

The Voyagers’ primary purpose was to fly by Jupiter and Saturn. If all the scientific objectives were met at Saturn, then Voyager 2 would be targeted to continue on to Uranus and Neptune.

At each planetary encounter – running on power equivalent to the light bulb in your refrigerator – the Voyagers would transmit photographs and scientific data back to Earth before being accelerated towards their next target by the planet’s gravity, like a slingshot.

Timed to take advantage of a favourable alignment of the outer planets not expected to recur for another 175 years, Voyager 2 launched first on August 20, 1977, followed by Voyager 1 on September 5. Although launched second, Voyager 1 was sent on a faster trajectory and was timed to arrive at Jupiter ahead of Voyager 2.

When Voyager 1 arrived at Jupiter in 1979 the mission’s scientific discoveries began.

Jupiter revealed close up

The world watched as the Voyagers’ cameras sent back – via the tracking stations – close up images of Jupiter and its moons, letting us see these worlds in detail for the very first time.

From the turbulence surrounding huge storms on Jupiter, to a volcano erupting on Jupiter’s moon Io, to hints that the icy surface of Europa probably conceals an ocean underneath, the Voyager mission started to reveal the outer Solar System to us in inspiring detail.

Indeed, during the course of their 12-year mission, the Voyagers discovered 24 new moons orbiting the outer planets and refined NASA’s use of the Deep Space Network to listen to signals from distant spacecraft.

To Saturn and beyond

After Jupiter, both Voyagers went on to encounter Saturn. Voyager 1 achieved the major goal of closely approaching Saturn’s giant moon, Titan.

Following this encounter, with its primary mission ended, Voyager 1 was flung on a northward trajectory above the plain of the orbits of the planets. Voyager 2 was subsequently targeted to travel outward on an extended mission to visit the next two gas giant worlds.

When Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in January 1986, the signals being received were much weaker than when it flew by Saturn, five years earlier.

Consequently, CSIRO’s radio telescope at Parkes was linked, or arrayed, with NASA’s dishes in Canberra to boost Voyager 2’s weak radio signal.

This was the first time an array of telescopes had been used to track a spacecraft. Yet this array would be insufficient to receive the even fainter signals expected when Voyager 2 reached Neptune in 1989.

So in the time between the encounters, NASA expanded Canberra’s largest dish from 64 metres to 70 metres in diameter to increase its sensitivity, and then linked it again with the Parkes 64 metre dish, to maximise the data capture at Neptune.

The increased size and sensitivity of the Canberra dish also meant that it was able to support Voyager’s ongoing journey beyond the outer planets.

The Pale Blue Dot

In 1990 Voyager 1 turned its cameras towards home. The resulting photograph, known as the Pale Blue Dot, is our most distant view of Earth, a fraction of a pixel floating in a deep black sea.

The legendary astrophysicist Carl Sagan, involved with Voyager since its inception, reflected that this distant view of the tiny stage on which we play out our lives should inspire us “to preserve and cherish that pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known”.

Both Voyagers have long since left the outer planets behind, two explorers heading into the galaxy in different directions, still sending data back to Earth and answering questions we didn’t even know to ask when they were launched 40 years ago.

Read more: The pale blue dot and other 'selfies' of Earth

Voyagers only talk to Australia

The Canberra tracking station continues to receive signals from both Voyager spacecraft every day, and is currently the only tracking station capable of exchanging signals with Voyager 2, owing to the spacecraft’s position as it heads on its southward path out of the Solar System.

Due to their respective distances, tens of billions of kilometres from home, the signal strength from both spacecraft is very weak, only one-tenth of a billion-trillionth of a watt.

In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first spacecraft to have entered interstellar space, the region between the stars. Lying beyond the influence of the magnetic bubble generated by our Sun, Voyager 1 is able to directly study the composition of the interstellar medium, for the first time.

Voyager 1 is still receiving commands that can only be sent from Canberra’s dishes. It is the only station with the high-power transmitter that can transmit a signal strong enough to be received by the spacecraft.

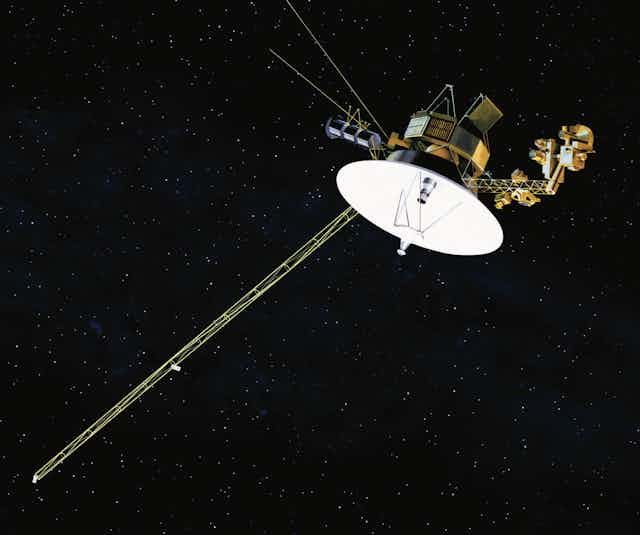

It has been an epic voyage for two spacecraft no bigger than small buses, two brilliant robots with an eight track tape deck to record data and 256kB of memory.

A golden message

The scientists and engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, who built the Voyagers and continue to operate them, planned ahead for Voyager’s legacy and its journey beyond our Solar System.

On board both spacecraft they placed a golden record, similar in concept to a vinyl record, featuring one and a half hours of world music and greetings to the universe in 55 different languages.

The cover art features a pictorial representation of how to play the record and a map reference to Earth’s location in our galaxy based on the positions of surrounding pulsars.

By 2030, both Voyagers will be out of power, their scientific instruments deactivated, no longer able to exchange signals with Earth. They will continue on at their current speeds of more than 17 kilometres per second, carrying their golden records like messages in bottles across the vast ocean of interstellar space.

Heading in opposite directions, southward and northward out of the Solar System, it will be 40,000 years before Voyager 2 passes within a handful of light years of the closest star system along its flight path, and 296,000 years before Voyager 1 passes by the bright star Sirius.

Beyond that, we may imagine them surviving for billions of years as the only traces of a civilisation of human explorers in the far reaches of our galaxy.