Today, Microsoft launches their new console, the Xbox One, around the world, starting with an absurdly spectacular light show in Sydney Harbour. Meanwhile, Sony’s new console, the Playstation 4, arrived last week in America, and touches down in Australia in a week.

Console generations have always served as the main markers on the timeline of videogame history. They traditionally mark monumental shifts in how videogames are imagined and designed.

On this occasion, however, in addition to the usual hype that marks a new console generation, there is an undercurrent of apathy. It’s as though things just aren’t nearly as exciting this time.

First, let’s talk about this idea of “generations”.

Is new always better?

The very word suggests a sense of moving forward, of leaving the past behind and aiming towards something somewhere ahead of us.

Videogames have always been intimately tied to technological advancement. For decades, we’ve believed that a “better” videogame is afforded by “better” technology (more polygons, more processing power, better AI and so on).

The videogame industry has cultivated this belief to create a perpetual upgrade culture, where every five or so years, enthusiasm is stoked with new consoles that, finally, will be able to achieve what the last generation couldn’t.

Few videogame players my age could forget, for instance, that first time seeing Mario run around a 3D world in Super Mario 64, after the flat 2D worlds of the Super Nintendo. The future is exciting.

This generation is no different, with the notable exception of being one of the longest generations ever, coming it at eight years between the Xbox 360’s release and the Xbox One.

When the Playstation 4 was announced, game designer David Cage made the incredible announcement that “getting the player emotionally involved is the holy grail of all game creators… with the Playstation 4, games have now finally reached that stage.” Finally!

Cage (and through him, Sony) is trying to convince an audience that they have never before felt emotionally involved in a videogame because technology has held them back. We have never been at war with Eurasia.

Console generations must, at the same time, erase history even as they build on it. We see this in the very names of the new consoles.

The Xbox One is the third Xbox console, but that “One” makes a claim to a new era: everything before now was prehistoric, but now we will have real games.

Playstation, meanwhile, have not forgotten how to count. Playstation 4 is indeed the fourth Playstation console. Here, instead of a refusal of history, we get the sense that history was leading us to this point where, finally, we have the power to produce good games.

Either way, whether history is silenced or invoked, each new console generation sells itself as being the end of history. Finally, we have arrived.

But this generation feels different. This isn’t the leap from Super Mario Bros. to Mario 64. This isn’t even the leap from Halo 2 to Halo 3. Many of the most highly anticipated games for the new consoles were already out on Xbox 360 and Playstation 3 several weeks ago with slightly lower texture resolutions. The new games, meanwhile, don’t look that much more impressive than the games we’ve seen the past eight years on this generation.

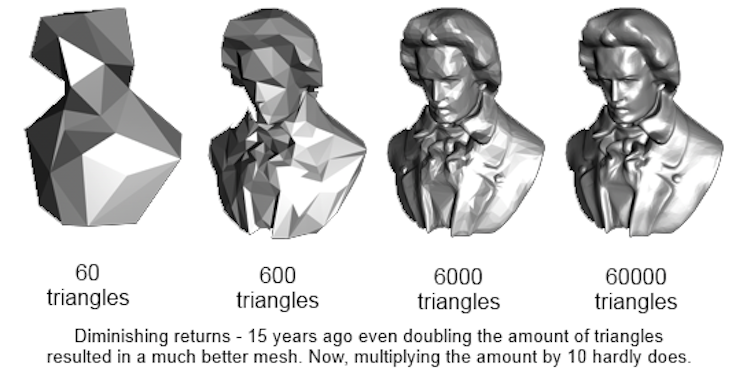

Two reasons for this: one, the diminishing return of adding more polygons (see image).

Two, in the eight years of this generation, we’ve seen entirely new strands of videogames emerge that have thrown spanners into the mainstream industry’s rhetoric of better-technology-equals-better-games.

The rise of indie games, casual games, and mobile games have all demonstrated that great game design isn’t necessarily connected to technological advancement. Vlabeer’s Super Crate Box, Rovio’s Angry Birds, Halfbrick’s Fruit Ninja: all great and successful games that have released since the last time we got new consoles.

The notion that better technology will lead us to better games feels more like a marketing stunt now than it ever has before.

Incremental change

Of course, one only has to look at Apple to know that an upgrade being incremental isn’t going to stop people getting excited about it. But, at the same time, there’s an air of cynicism this time as the videogame generation finds itself having to write Year Zero at the end of one of the longer generations ever.

As Leigh Alexander asks at website Gamasutra: Who cares?

Ultimately, the notion of console generations, of giant leaps forward once every five years, seems unsustainable going into the future. Jumps in technology are just not that exciting when videogames are continuing to do incredibly exciting things with the technology they’ve already had for decades. They’re also not that exciting when you’ve had the same console for eight years already and you are quite comfortable where you are.

Instead, what I think we’re going to start seeing more of are incremental upgrades like Apple does with iPhones, or like Nintendo has long done with their portable devices. The myth of upgrade culture isn’t going to go away, it’s just going to accelerate to a pace where audiences won’t be allowed to get comfortable. Instead of giant leaps every five years, we’ll be taking small steps every other one.

And, of course, these “generations” apply to an increasingly niche fraction of videogames. Mobile, casual, social, PC, and indie games largely exist outside of console generations.

Further, for many videogame players, the huge price tag that comes with a next-gen console renders them not even worth considering. The same people are getting excited about a new generation, but those same people are much less representative of who plays videogames than they used to be.

What was once a huge moment for all videogames is now just a not-quite-so-huge moment for one part of a much more heterogeneous medium. Generations just aren’t what they used to be.