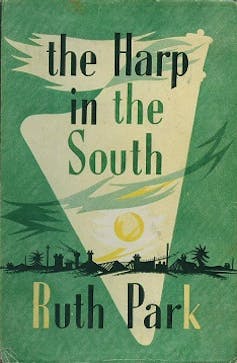

Ruth Park’s novel The Harp in the South (1948) is a classic of Australian fiction. Just as television viewers in recent decades would recognise “Ramsay Street” as the fictional centre of Australia’s longest-running television soap opera Neighbours, earlier generations of readers would have recognised with affection “Twelve-and-a-half Plymouth Street”: the hearth and home of Harp’s fictional Irish-Australian family, the Darcys.

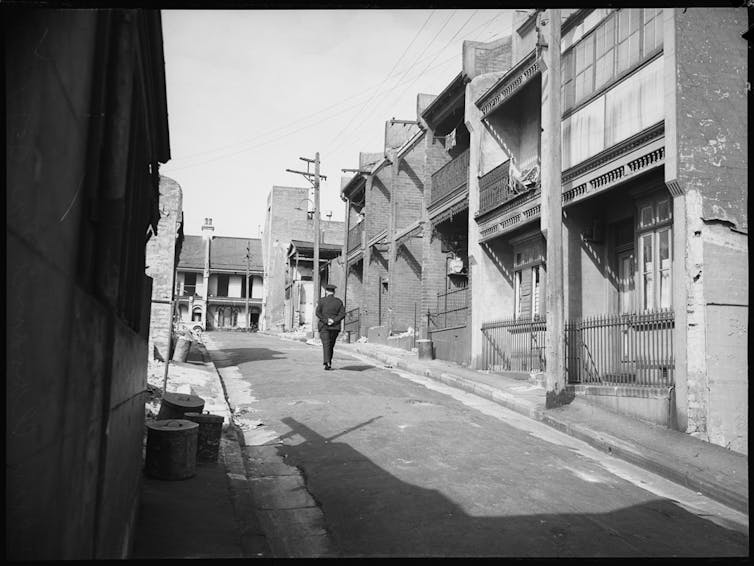

This fictional street exists in an actual inner-urban neighbourhood, and this mattered to how the novel was first read. Readers of the time expressed strong reactions to Harp’s depiction of Sydney’s Surry Hills.

The novel depicts the built, settler-colonial environment of Surry Hills, along with other parts of the land First Nations people know as “Country”. On first publication in Australia at least, character Charlie Rothe’s Aboriginal ancestry – and his relation to Country – appear to have passed unremarked.

‘Dickens from Australia’ grew up in New Zealand

The novel was first serialised in the pages of the Sydney Morning Herald, after winning the newspaper’s first novel-writing competition. It became an instant hit. Fans impatient to read the latest instalment joined long queues outside newsstands and bookstalls.

But not all readers were enamoured with it. One Sydney resident called it a “wallow in depravity, filth and crime” that should “be banned from the homes of many decent citizens”, in the Herald’s double-page spread of responses to the book.

In her own letter to the Herald, responding to the moral panic her novel had generated, Park wrote that her intention was to show how “splendid characters full of honesty and loving kindliness, can exist against a squalid and often tragic background”.

US author Sterling North named Park the “Female Dickens from Australia”. But Park was not originally “from Australia”. She was born in Auckland, New Zealand.

Interestingly, in letters to long-term pen-friend and future husband D’Arcy Niland, written before 1942 when she migrated to Australia and married him, Park signs off with such Māori salutations as “Kia Ora” and refers to her home country as Māoriland.

The hills are full of Irish people

The hills are full of Irish people. When their grandfathers and great-grandfathers arrived in Sydney they went naturally to Shanty Town, not because they were dirty or lazy, though many of them were that, but because they were poor.

These lines introduce the novel’s Darcy family, whose loves and losses animate the pages that follow. Grandma Darcy loves to smoke her “little clay cutty” in bed. Family patriarch Hughie Darcy argues with fellow resident and Orangeman Patrick Diamond, especially when Hughie is affected by the “demon drink”. Hughie’s alcoholism impoverishes an already poor family.

Hughie’s devoutly Catholic wife, Margaret “Mumma” Darcy, mourns the loss of her eldest child, Thady, who had one day wandered away from the front doorstep where he had been playing. Mumma searches for, but never finds, this missing boy.

Roie (Rowena) is the elder of the two Darcy daughters. Through her, Park explores sex outside of marriage, unwanted pregnancy and abortion – the topics that unsettled readers on first publication. After she becomes pregnant following a night with local boy Tommy Mendel, Roie seeks out the back-alley services of a woman who administers abortions.

Afraid and ashamed, Roie flees the scene, only to be violently assaulted by a gang of drunken sailors whom she has the misfortune of encountering on her way home. They beat her to the ground, precipitating a miscarriage.

Roie’s crisis coincides with another emerging story: that of Charlie Rothe, who will come to live at Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street as her husband. Something in this story reverberates down the decades, summoning recognition of an historical tragedy.

Who is Charlie Rothe?

Charlie Rothe appears in the story as Roie is recovering from the miscarriage and its ongoing side-effects. Roie is overcome by dizziness at the live venue of a radio quiz her sister Dolour has just won. Charlie suddenly appears and helps her to a seat.

This stranger is introduced via the narrator’s description of his voice.

Noises were already fast fading into a babble of sound. Then a voice said, “What’s the matter? Are you feeling sick?”

It was a hollow, echoing voice like thunder on a heath. Roie tried to answer it and couldn’t. It sounded again, frightening her a little, then she felt someone lower her into a seat.

Like Emily Bronte’s Heathcliff, Charlie is an orphan child whose unknown origins become the source of speculation about parentage and race.

This speculation arises when Charlie becomes part of the Darcy household. Dolour and Mumma ask Charlie about his parents, having assumed he is an Aboriginal man.

“They died when I was about seven, I think,” responds Charlie, who knows only that a “bagman” had raised him. “He just picked me up, I was sitting by a fence, yowling my head off, and he asked me to come along with him, and I went.” At this point, Charlie’s “eyes looked back into the past and saw the endless dusky, dusty roads of New South Wales”.

True to her declared intention to create “splendid” yet “squalid” characters against a “tragic” background, Park does not shy away from depicting Hughie and Mumma’s prejudices toward Charlie.

They fear Roie and Charlie will one day have a child, imagining what it would mean to nurse “a sooty grandchild”. Yet, Hughie and Mumma will come to love both Charlie and their granddaughter.

Read more: Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë and the truth about the 'real-life Heathcliff'

A mixed-race romance

For Roie does give birth to Charlie’s child. They name her “Moira”, an Irish name meaning both “drop of the sea” and “destiny, fate”. With its romance between an Irish-Australian woman and an Aboriginal man, Harp stands apart from white-authored novels of the time, whose depictions of Aboriginal characters reflect eugenicist beliefs that Aboriginal people were a “dying race”.

Charlie loves Roie and she loves him. However, in the sequel novel, Poor Man’s Orange, Roie dies giving birth to her and Charlie’s second child, Michael. Charlie is rocked by her death, but eventually he and Roie’s sister, Dolour, develop an intimate attachment. Charlie will have a future with Dolour, as do his children with Roie, Moira and Michael.

A relative stranger to Australian shores, Park brought into her novel an Aboriginal character who had become estranged from both his people and his Country. So it’s significant that, in the concluding chapter of Poor Man’s Orange, Charlie asks Dolour to come “outback” with him and the children.

The Macquarie Dictionary defines “outback” as “remote, sparsely inhabited back country” that had been “romanticised in some Australian literature”. Given that his memory is of a “dusky, dusty” New South Wales road, Charlie’s “outback” is not quite the same space as that conjured in certain white-authored worlds.

Toward the end of Poor Man’s Orange, three years after Roie’s death, Charlie and Dolour go walking at night to the shores of Botany Bay. Charlie proposes to her that she come with him “outback”, and she accepts.

Music spilled across the street like the yellow light that spilled from the tall corner-lamp slung in its archaic wrought-iron bough. But mainly there was silence, as though already Surry Hills felt its doom, and down in the earth the old grass-roots were stirring, ready to clothe this soil with the verdure that had been there a century before.

It is not an Aboriginal character who faces his doom: it is Surry Hills, an urban environment built by colonial-settlers.

The future of an Aboriginal character

It is “down in the earth” that “the old grass-roots were stirring”. The “verdure” that springs back to life matters to how we understand Park’s Aboriginal character and his relationship to Country.

Charlie’s invitation to Dolour to come “outback” with him and his children changes the meaning of “outback”. In this context, “outback” can be understood as Country that had been occupied and cared for long before colonial invasion.

A mixed-race romance survives and thrives at Twelve-and-a-Half Plymouth Street. This is remarkable, given laws against miscegenation had been in place in some Australian states as late as 1940, negatively affecting attitudes to “mixed-descent families”.

Like Charlie and his children, The Harp in the South has had a future. Since publication, it has been adapted for stage, radio and television: both at home and abroad.

In 1987, two years after the first episodes of Neighbours introduced us to its three white families living on Ramsay Street, The Harp in the South miniseries was televised. Actor Shane Connor – who would go on to play Ramsay Street resident Joe Scully – was cast to play Charlie.

The Harp in the South has been translated into 37 languages. It is reputed never to have been out of print. Its enduring popularity is a testament to its author’s very considerable skill as a writer. Park draws on romance and other familiar genres to tell a story about Irish-Australian community in Sydney.

And in 2023, it is possible to see – threaded through the novel – a story about First Nations people, dispossession and ongoing attachment to Country.