Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and/or images of deceased people.

The most startling point on the referendum for a Voice to parliament is the fact the majority of people in this country have no idea of history. And I mean both Black and white people.

Australian history, as written for nearly two thirds of the 20th century, glorified discoverers, explorers, settlers, and Gallipoli. We as Aboriginal people had been conveniently erased from the historical landscape and memory. Most Australians gave Aboriginal people little or no consideration. The majority of Aboriginal people were trapped in a historical vacuum through the fact that great numbers of our people had been confined to heavily congested and controlled missions and reserves.

As part of this confinement, we were encouraged to forget our past. Everyday decisions were removed from people; they were told what to eat, what to wear, who you could marry, and their movement was severely restricted. There was a process of historical erasure and memory.

We were to be severed from any sense of past or inspiration. We could not participate in ceremonies, speak our language, tell our stories, practice songs and dances or conduct our everyday hunting and living experiences. Over time our people could only remember the controlled life on the reserve. It became the pattern of misery.

In his 1968 Boyer lecture, After the Dreaming, anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner exposed Australia’s failure to regard, record or acknowledge Aboriginal people in the country’s history. Australian history, he said, had been constructed with:

a view from a window which had been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape.

What is critically important in history understanding is that the call for a Voice to parliament is not a new initiative. Aboriginal activists nearly 100 years ago first called for a voice to parliament as part of their political platform and demands during the 1920s.

Read more: The 1881 Maloga petition: a call for self-determination and a key moment on the path to the Voice

The Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association

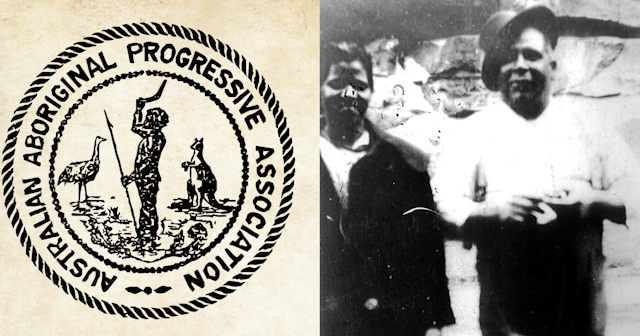

The first Aboriginal political organisation, the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA), was formed in Sydney in 1924 and led by my grandfather Fred Maynard.

It advocated several key demands in protecting the rights of Aboriginal people, centring on:

a national land rights agenda

protecting Aboriginal children from being taken from their families

a call for genuine Aboriginal self-determination

citizenship in our own country

defending a distinct Aboriginal cultural identity

and the insistence Aboriginal people be placed in charge of Aboriginal affairs.

The call for Aboriginal rights to land was explicit. Leader Fred Maynard declared:

The request made by this association for sufficient land for each eligible family is justly based. The Australian people are the original owners of the land and have a prior right over all other people in this respect.

The association’s conference in Sydney was front page news in the Sydney Daily Guardian.

Over 200 Aboriginal people attended this conference held at St David’s Church and Hall in Riley Street, Surry Hills.

In the space of six short months the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association had expanded to 13 branches, four sub-branches and a membership in excess of 600.

Its established offices in Crown Street, Sydney and a state-wide network of information regarding Aboriginal people.

Calls for direct representation in parliament

Late in October 1925, the association held a second conference in Kempsey, New South Wales. It ran over three days with over 700 Aboriginal people in attendance.

It was noted in press coverage of the conference that

pleas were entered for direct representation in parliament.

Two years later in 1927, the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association produced a manifesto. It was delivered to all sections of government – both state and federal – and published widely across NSW, South Australia, Victoria, and Queensland.

One of the significant points was for an Aboriginal board to be established under the Commonwealth government, and for state control over Aboriginal lives be abolished. It envisioned:

The control of Aboriginal affairs, apart from common law rights shall be vested in a board of management comprised of capable educated Aboriginals under a chairman to be appointed by the government.

This board would not be comprised of government-selected or handpicked individuals but would be Aboriginal elected officers.

This push for an Aboriginal board or place in parliament continued in 1929, when Fred Maynard spoke to the Chatswood Willoughby Labour League in NSW on Aboriginal issues. A report in the The Labor Daily newspaper in February that year mentioned his call for:

Aboriginal representative in the federal parliament, or failing it, to have an [A]boriginal ambassador appointed to live in Canberra to watch over his people’s interests and advise the federal authorities.

Surveillance, threats, intimidation, abuse

The Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association disappeared from public view in late 1929.

There is strong evidence the organisation was effectively broken up through the combined efforts of the NSW Aborigines Protection Board, missionaries, and the police.

The state government and the Protection Board had been embarrassed by the exposure of their unjust policies in the media and wanted the organisation broken up.

Fred Maynard, in a newspaper interview in late 1927 in The Newcastle Sun revealed the level of surveillance, threat, intimidation, and abuse he and the other Aboriginal activists were subjected to. The report noted:

He said that he had been warned on many occasions that the doors of Long Bay were opening for him. He would cheerfully go to jail for the remainder of his life, he declared if, by so doing he could make the people of Australia realise the truly frightful administration of the Aborigines Act. He knew cases where children had been torn from their mothers and sent into absolute slavery.

When one ponders upon the legacy of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association the sad reality is that if the demands of these early activists had been met nearly a century ago, we would not be suffering the severe disadvantage that hovers over Aboriginal lives still today.

Imagine if enough land for each and every Aboriginal family to build their own economic independence had been granted.

Or that we would not have suffered another five decades of Aboriginal child removal and the shocking impact of that policy on generations of Aboriginal lives.

If the demand to protect a distinct Aboriginal cultural identity had been taken up, we would not today be working to piece together the shattered cultural pieces of language, stories, songs, and dances.

And finally, if Aboriginal people had been placed in a position to oversee Aboriginal policy and needs, the history of our people would have been vastly different.

The reality today is we continue to fight for the demands that the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association established nearly 100 years ago.

Read more: Capturing the lived history of the Aborigines Protection Board while we still can