This year is the centenary of Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We – a major influence on George Orwell’s dystopia 1984, as well as an important early contribution to the burgeoning genre of science fiction.

We and 1984 (published in 1949) were crucial influences on Cold War western imagination of the Soviet Union as a totalitarian state. But Orwell had never been there, and Zamyatin wrote his dystopia in 1920, a time of chaos and civil war just three years after the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia and two years before the Soviet Union formally came into being.

Both novels portray a state in which the individual has been merged into the collective: “I” has become indistinguishable from “we”. The state is run by a remote but all-seeing leader (the “Benefactor” in Zamyatin, “Big Brother” in Orwell), who is revered as the font of wisdom and universal wellbeing. The leader is backed up by a secret police (the Guardians, the Thought Police), who organise the disappearance of potential trouble-makers.

Life is meticulously regulated according to a state plan, leaving only a minimal personal sphere. In Zamyatin’s novel, houses are all glass. The only time the blinds can be lowered is for the regular hour of sex with a registered partner. Thinking differently is an offence against the state.

In both novels, falling in love is the fateful assertion of an “I” that is not part of “We.”

Read more: Guide to the classics: Orwell's 1984 and how it helps us understand tyrannical power today

An instinctive satirist

Zamyatin wrote his novel while living in a special House of the Arts in Petrograd (now St Petersburg) under the protection of the writer Maxim Gorky, who used his clout with Bolshevik leaders to shelter writers and artists from the worst privations of the Civil War period and the newly established revolutionary police, the Cheka.

It might be assumed that Zamyatin was one of many members of the Russian intelligentsia who, having been fashionably radical under the Tsar, recoiled from the reality of rampaging mobs and social and political breakdown that led to the Bolsheviks taking power in October 1917. In fact, Zamyatin had been a Bolshevik, although he was no longer an active party member.

He was born in 1884 in Lebedian, a town 370 kilometres south of Moscow, undistinguished except for its race track. His father was a priest (the lower rungs of Orthodox clergy were allowed to marry) and his mother, surprisingly, a pianist. This would have made them provincial intelligentsia, marginal to almost all their neighbours.

Judging by his bleak memories of Lebedian, Yevgeny was a lonely child who took refuge in reading. Having become a socialist as a teenager, he joined the Bolshevik party in time to participate in the revolutionary upheavals of 1905 in the capital, where he was a student at the St Petersburg Polytechnic.

Arrests and exile to the provinces followed, but he nevertheless managed to graduate as a ship-building engineer. He also started writing, winning praise from the critics for his vivid portrayal of provincial boredom and inertia in a novella, Uyezdnoye (A Provincial Tale), published in 1913.

The Russian government sent Zamyatin to England in 1916 to work on the building of ice-breakers at the Newcastle docks, so he missed the February Revolution and the ferment that followed. He returned just before October in an “antiquated little British ship”. The journey took about 50 hours, the passengers in lifebelts the whole time due to the threat from German submarines.

His late arrival for the revolution was something he always regretted – it was like “never having been in love and waking up one morning ten years married”. But it is difficult to imagine Zamyatin succumbing to the euphoria that gripped the Russian intelligentsia in 1917. He was a born loner and instinctive satirist, whose usual response to collective enthusiasm was to dissent.

Read more: World politics explainer: the Russian revolution

It was the oddness of the situation after October that struck Zamyatin first. He remembered the winter of 1917-18 as “merry, eerie […] when everything broke from its moorings and floated off somewhere into the unknown”.

Revolutionary Russia, with its privations, dysfunctions, identity adjustments and lofty rhetoric, provided many opportunities for satire. The genre flourished throughout the 1920s in the work of writers such as Mikhail Zoshchenko, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov.

This was for the most part the satire of insiders, rueful and affectionate, rather than that of regime critics. Bulgakov, to be sure, ran into political trouble in the late 1920s with his novel The Master and Margarita, but the books of Ilf and Petrov, featuring their Soviet conman hero Ostap Bender, became Soviet classics, loved by generations of Soviet children as well as adults.

Zamyatin’s satire was colder and harsher. To be a heretic, whether the regime was Tsarist or Soviet, was an internal necessity for him – and, he argued, for “true literature”. He despised the “nimble” writers and artists – “futurists”, “proletarians”, and so on – who jumped on the Bolshevik bandwagon and curried favour with the new regime, proclaiming themselves “the court school” and filling the air with their “yellow, green and raspberry red triumphant cries”.

In the highly political and factionalised world of the arts in early Soviet Russia, this disdain was energetically returned. Denunciation in the literary journals was one of Zamyatin’s perennial problems. He had trouble with the Cheka, too, which arrested him several times.

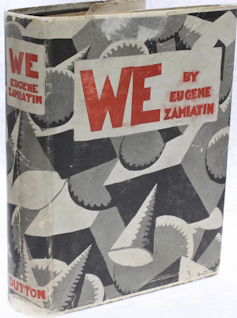

Written in 1920, We was turned down for publication by Soviet censors. An American publisher, E.P. Dutton, would produce the first complete edition in 1924, in Gregory Zilboorg’s English translation. The novel would not be published in the Soviet Union until 1988.

Cogs in the machine

We depicts a future society in which almost everyone willingly, even eagerly, sacrifices their individuality to become cogs in the machine, with the Guardians there to deal with any dissenters.

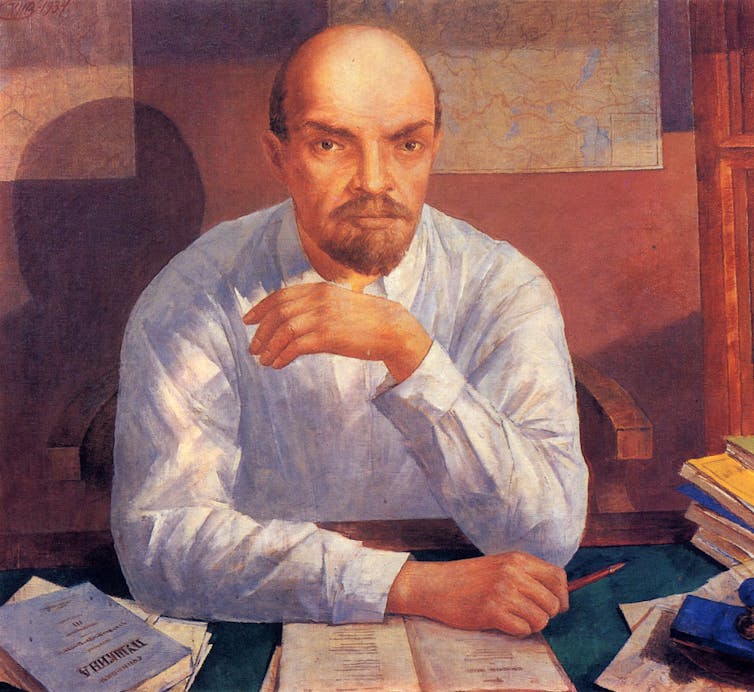

Clearly, Zamyatin’s experiences with the Cheka, the censors and his conforming writer colleagues were part of his inspiration. The Benefactor’s “socratically-bald head” was no doubt a swipe at Lenin, but his moral smugness probably owes something to Felix Dzerzhinsky, the first head of the Cheka.

For educated contemporaries, however, the Benefactor had loftier literary antecedents: Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor from the Legend of the Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov and Vladimir Solovyev’s Antichrist in Tale of the Antichrist.

Both of these stories have a spokesman for institutionalised collective wisdom (the established Christian church) make the argument against a heretic (Jesus), with whom the authors’ sympathies lie. Zamyatin – a priest’s son, though he had abandoned Christianity in his youth – called the emerging orthodoxy of the Bolshevik Revolution “a new branch of Catholicism, which is as fearful as the old of every heretical word”.

The totalitarian society described in We may have been the Soviet future, but it was far from the Soviet reality when Zamyatin wrote. In the first years after the revolution, the Bolsheviks were trying to run Soviet Russia under an improvised system later called “War Communism”. This meant nationalising everything in sight and using force, rather than market relations, to extract grain from the peasantry and feed the cities and the Red Army, which was fighting foreign-backed White Armies on multiple fronts.

Soviet Russia was indeed cut off from the world, as Zamyatin’s dystopia is by the Green Wall, but at this point that was not the Bolsheviks’ choice. It was the result of war, foreign intervention and economic sanctions. The Bolsheviks believed in economic planning, but it would be ten years before they would seriously try to implement it.

In other words, the Bolshevik government in 1920 was as incapable of achieving the seamless regimentation of We’s dystopia as it was of building the space-craft that provides the novel with its science-fiction theme.

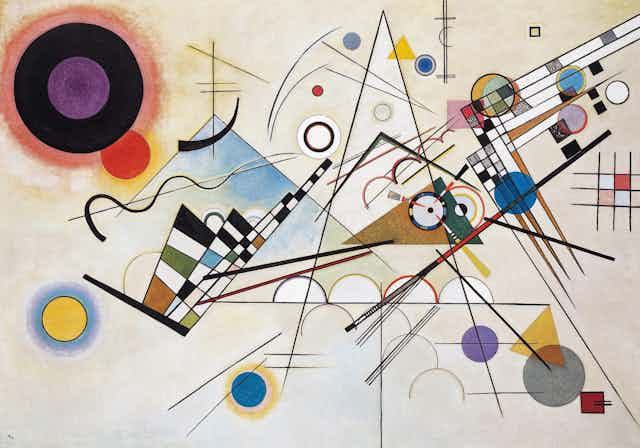

Zamyatin’s novel is often read as a prescient foretelling of Stalinism, ten to 15 years before it came into being. That could be. But Zamyatin was also drawing on a more immediate source: the vision of a regimented and mechanised Soviet society of the future – seen as a utopia, not a dystopia – that was being trumpeted by the same futurist and “constructivist” artists whose embrace of the Bolshevik Revolution Zamyatin found so suspect.

A particular target, mentioned several times in We, was the worker poet Alexei Gastev. Like Zamyatin, Gastev was a longtime Bolshevik revolutionary. In 1920, he set up a Central Institute of Labour whose mission was to train workers to function like machines.

This revolutionary version of the American capitalist concept of Taylorism was aimed at maximising worker efficiency to increase productivity and profit. It did not go down well with the Soviet industrial ministry, still less with Soviet trade unions. It was closed down at the end of the 1920s, about the time serious industrialisation got underway.

But revolutionary regimentation of life, the cult of the machine, and submerging of the individual in the collective were staples of the “futurist” imagination, explored not only by Gastev, but the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold, and constructivist artists like Vladimir Tatlin.

The revolutionary avant-garde had great artistic achievements to its credit, but tolerance was not one of its characteristics. It bullied writers and artists who did not conform to its ideas, frequently appealing to the authorities (usually the Communist Party, but sometimes the Cheka) to put their opponents out of business.

That is one of the subtexts of Zamyatin’s 1921 essay I Am Afraid, as he was one of the major targets. The Russian Association of Proletarian Writers, a group claiming (with only partial accuracy) to represent the Party, imposed a dictatorial local rule on literature in the 1920s. It gave Zamyatin a relentless bashing – particularly after parts of We were published (perhaps without Zamyatin’s knowledge) in bourgeois Czechoslovakia.

This was the context of Zamyatin’s famous letter to Stalin in 1931. Stalin was already looking more like the Benefactor than Lenin had ever done, but he occasionally intervened to protect writers who were the Association’s victims. Zamyatin asked permission to go abroad with his wife because he was unable to work in the “atmosphere of systematic persecution that increases in intensity from year to year”. He named, in particular, the Association’s Leningrad branch and the weekly literary journal it controlled.

Zamyatin phrased the request to leave, which Stalin approved, as a temporary one. He left open “the right to return as soon as it becomes possible in our country to serve great ideas in literature without cringing before little men”.

In fact, the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers was dissolved by government decree on Stalin’s initiative the next year. Zamyatin’s sometime patron, Maxim Gorky, who had departed for Europe earlier, returned to the Soviet Union. Zamyatin did not.

Perversely, although English was his best language and he was often called “the Englishman” in Russia, he went to France, a centre of Russian émigré culture, whose opinion-makers he anticipated would boycott him because of his Bolshevik past.

After some unhappy and lonely years, still a Soviet citizen, Zamyatin died of a heart attack in Paris in 1937 – the year of the Great Terror which, had he remained in the Soviet Union, would probably have killed him.

Read more: What Stalin’s Great Terror can tell us about Russia today