I don’t often re-read books, partly because there are so many on my unread pile. There are just a few that I go back to over and over again: Pride and Prejudice, Middlemarch, The Bell Jar – and Lucky Jim. Some mistake surely? How can a bookish feminist include this woman-baiting novel on a list of all-time favourites?

The story is of its time, but the predicament of the protagonist is universal. Jim Dixon is a junior lecturer at a redbrick university in an unnamed English town in the 1950s. He is trapped in his own life, hemmed in by a snobbish and moribund society and in thrall to people he despises. Jim’s mortal enemy is his boss Professor Welch, a man almost throttled by own his pretentiousness, while his relationship with his accidental girlfriend Margaret Peel is equally problematic. Cowardice and deceit vie with his reluctant decency; he knows he doesn’t have the courage to be an outright cad like Catchpole, who (apparently) dumped Margaret and prompted her failed suicide attempt.

Published 60 years ago, this seminal book is the precursor of the campus novel which is still a feature of the literary landscape. Amis was one of the supposed “Angry Young Men” alongside John Osborne, John Wain and Colin Wilson. And there’s anger. Jim Dixon is furious about the privately educated pseuds and chancers who are in charge. This doesn’t make the story dated. Dixon is tormented by suppressed irritation, like Basil Fawlty, and the awkwardness of his social interactions prefigure those of David Brent in The Office. Like the best British sitcoms, Lucky Jim is about claustrophobia and class.

This might not sound very guilt-inducing: analysing social dysfunction and conflict is all very erudite. So why is this a guilty pleasure? For many readers, it’s the sexist tone and assumptions which underpin Amis’s work that are alienating and offensive. But Jim Dixon is not a misogynist. The Amis take on women in this novel isn’t exactly Flaubertian, but his truly anti-feminist work came later, in his Angry Old Man period. (Check out Stanley and the Women if you want to read him in full flow.)

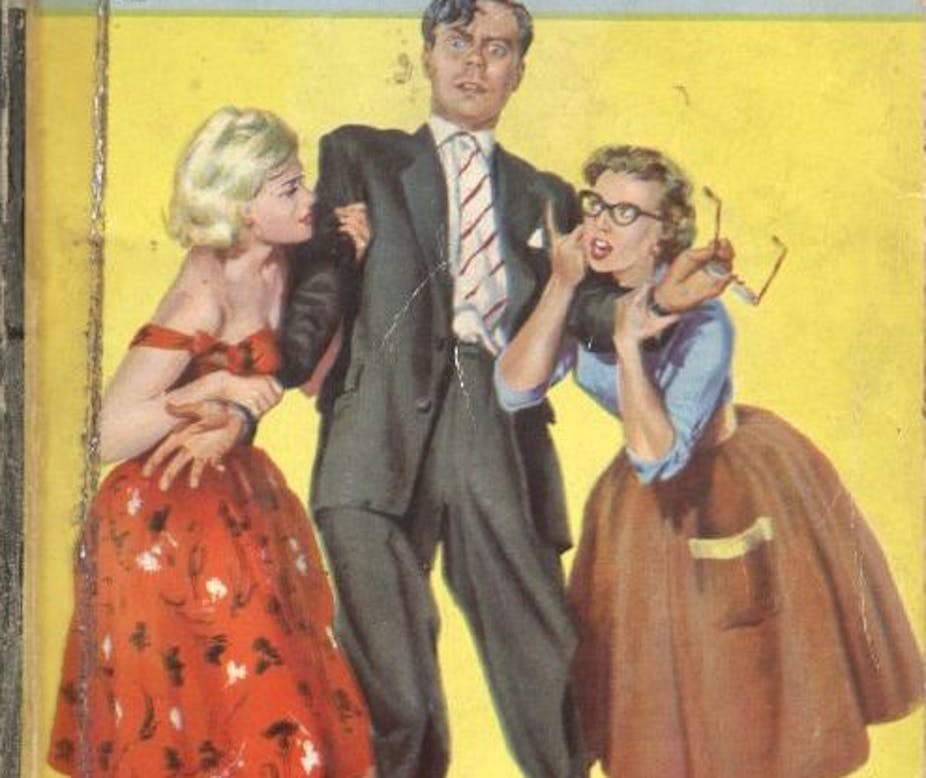

But the perspective is still assertively masculine, and Jim’s viewpoint is the satiric norm from which all the other characters are judged. His attitude to Margaret makes for uncomfortable reading, and Amis skews the plot to suggest that Margaret isn’t worthy of the reader’s sympathy. It’s also true that Jim’s love interest, Christine Callaghan, is very thinly drawn compared to the desperate and Machiavellian Margaret. In fact, her dominant characteristic is that she is attractive.

All in all this probably doesn’t seem to make for a feminist author’s favourite read. But somehow, it does. I’m not sure Margaret is really treated less fairly than the ludicrous Mr Collins in Pride and Prejudice. Or the pedantic, obsessive Casaubon, one of the most unappealing characters in Middlemarch. Both Collins and Casaubon commit the crime of being sexually unappetising, and blocking the heroine’s path to true love, just as Margaret is an impediment to Jim’s romantic ambition.

One gender is ridiculing another – but surely we can deal with this? We are happy enough when the perspective is a female one. When Elizabeth Bennet asks her father if Mr Collins can be a “sensible man”, the irony is that there are no sensible men in the novel, least of all the egregiously snobbish Mr Darcy.

So perhaps my pleasure is not so guilty. Above all, I like Lucky Jim because it’s funny. The comic set pieces have never been bettered, from Professor’s Welch’s appalling driving to Jim’s climactic drunken lecture on “Merrie England”. Amis is relentlessly elegant and stylish, deploying wickedly adroit dialogue and sharp social observation. My favourite scene is the one in which Jim, a weak-willed smoker, burns a hole in the bed sheet at Welch’s house, and attempts to cut out the cigarette burn with a razor-blade while painfully hungover. Inevitably, he makes a bad situation worse.

Jim’s furtive attempt to conceal the damage he has done is a metaphor for his whole existence. Ultimately his rebellious nature is revealed. The novel is a celebration of such rebellions, a harbinger of the 60s and the social revolution that changed everything. I can forgive a bit of sexism along the way.

Guilty Pleasures is a summer series in which academics reveal their most embarrassing cultural inclinations. Over the next few weeks, you’ll find out what literature professors delve into on holiday, when they can’t quite bear to crack into that next classic.