27 December 2023 marks the centenary of the death of the French civil engineer, Gustave Eiffel. Many studies have looked at the way in which the tower that bears his name has inspired painters (Bonnard, Chagall, Delaunay, De Staël, etc.) and poets (Apollinaire, Cendrars, Cocteau, Queneau, etc.) since it was built in 1889 for the Universal Exhibition commemorating the centenary of the French Revolution. But its presence in silent cinema, which coincides with the monument’s construction, has remained in the shadows.

When the cinematograph was born in 1895, six years after the Iron Lady, the new medium was immediately drawn to the tower. In the digitised GP Archives catalogue, for example, 121 entries out of 2,091 are given for “ Eiffel Tower ” between 1895 and the start of talking pictures in France. And yet this is a period for which many reels have not survived, notably because 35mm film was made of cellulose nitrate, which is flammable and fragile.

In documentary cinema from 1897

In 1897, a Lumière cinematograph was taken up for the first time in the Tower’s lift, regaling us with a dizzying 42-second panorama of the Trocadero Palace, with the Tower’s metal frame in the foreground. This premiere may not come as a big surprise from the Lumières brothers, who were fond of capturing images of iconic landmarks, but the originality lies in the form of the sequence, which boldly superimposes foreground and background shots to better “ embark ” viewers.

The presence of the tower is more surprising in the creations of Georges Méliès, best known for his fairy tales and trick films. Méliès made around thirty one-minute films about Paris between 1896 and 1900, some of which showed the Champ-de-Mars and the Eiffel Tower during the 1900 Universal Exhibition.

That same year, the Lumières tried out an experimental format, 75mm, and once again put the Eiffel Tower in the spotlight.

Their slightly crazy idea was to project this tape onto a gigantic 720 m2 screen during the Universal Exhibition – for reference, the largest screen in Europe today is the “ grand large ” of the Grand Rex, 282 m2. Unfortunately, construction of the appropriate projector was not completed in time and the screening never took place.

In fiction since 1900

In 1906, Georges Hatot directed La Course à la Perruque (in English: The Wig Chase) for the Pathé brothers, a 6-minute comedy strip packed with twists and turns, with a sequence that transported the viewer in front of, and then inside, the Eiffel Tower.

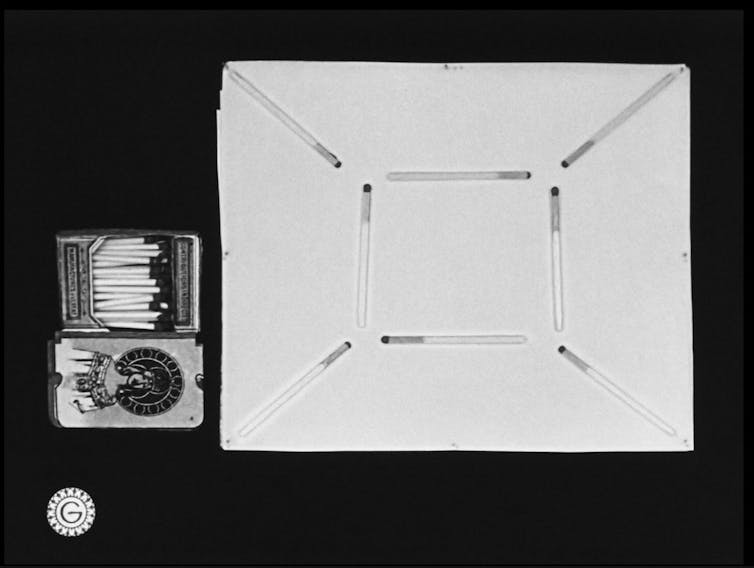

All cinematic genres seemed to be contaminated. The pioneer of animated cinema, Émile Cohl, created an imaginative and poetic animated film in 1910, Les Beaux-Arts Mystérieux (The Mysterious Fine Arts), a nugget of inventiveness shot frame by frame, in which the basis of the Eiffel Tower can be recognised through an arrangement of matches.

The craze endured for years. In the summer of 1923, René Clair, a young filmmaker with close ties to the avant-garde, shot Paris qui dort (The Crazy Ray), a medium-length film produced by Diamant Films, set mainly in the Eiffel Tower. The monument’s caretaker wakes up to find that the streets of the capital are empty. Clair followed this up five years later with La Tour (The Tower), 14 minutes of a kind of cinematic poem offering views of the Iron Lady from a variety of angles.

It was in the last years of the silent era that Jean Duvivier’s Le Mystère de la tour Eiffel (The Mystery of the Eiffel Tower) was released, a film in which the leader of a mysterious international organisation of hooded criminals, named Ku-Klux Eiffel, sends signals, via the Eiffel Tower, to his members scattered across Europe.

The inspirational power of the Eiffel Tower

These varied examples show just how much the Eiffel Tower inspired the pioneers of the cinematograph and the directors of the silent era.

If they included it in their documentaries, it was to illustrate this architectural feat, which took 26 months to build, and to show the extent to which it left its mark on people’s minds and on the Parisian landscape. It should be remembered that the tower did not meet with unanimous approval and that it was not destined to remain in place. In fact, its construction sparked an outcry from a number of artists, who went so far as to voice their protest on 14 February 1887 in the leading daily newspaper Le Temps, in a letter addressed to Adolphe Alphand, director of works for the Universal Exhibition. The signatories included the French poet and novelist, François Coppée, architect of the Palais Garnier, Charles Garnier, and writer, Guy de Maupassant.

Despite this opposition, the Eiffel Tower was erected and survived its scheduled demolition thanks to the monument’s scientific and strategic roles. A meteorological station was installed there in 1889 and antennae for wireless telegraphy were added from 1903.

As for the Tower’s presence in fiction films, it testifies to the impact of its architectural audacity, its mysterious aesthetic aura and its modernity the Tower inspires atypical stories, filmed thanks to innovative shots, ingeniously edited.

A glimpse into the history of silent cinema

If the presence of the Iron Lady in silent cinema has received so little attention in historical research, it is undoubtedly due to a lack of consideration and legitimisation of the cinematographic medium itself.

The first films were very short, at first lasting a few seconds and then a few minutes. They were shown at fairs, in town and village squares, in cafés and in some theatres. Cinematography was a very popular form of entertainment, often scorned by the elite. Strips of film were bought by fairground dealers who wore them down to the bone. When they broke, they cut them up and glued them back together, so that it was never quite the same tapes that were projected.

From 1907 onwards, there was an economic revolution. The Pathé brothers’ powerful company replaced the sale of copies with a rental system. This change altered the way distribution was organised, and in turn the way films were made and seen. The exploitation of films gave rise to an autonomous industry; screening rooms sprouted throughout in cities and films grew longer.

From 20 metres, or around 60 seconds, this increased to 740 metres, or 30 minutes, in 1909; to 1,500 metres, or one hour, in 1912; and even to 3,000 metres, or two hours, in 1913. Hybrid film shows mixed short films (news, comedy, animation, etc.) before or around a longer film, the core of the screening. The whole show featured attractions ranging from jugglers to poets and acrobats, and was accompanied by music ranging from a single instrument to an orchestra, depending on the size of the venue. While cinema may have been silent (talkies didn’t arrive until 1927), it was anything but!