Ever since Liz Truss’ fateful mini-budget of October 2022, the Labour party has enjoyed a commanding lead in the polls. Yet for many, its political vision has remained vague and undefined.

But now a clearer picture is beginning to emerge. In a speech to members of the UK’s financial sector in mid-March, the shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves outlined a wide-ranging economic plan.

Championing a growth strategy built around stability, Reeves argued that political volatility was a primary cause of Britain’s economic stagnation. In contrast to the policy churn and infighting that has characterised UK politics since the Brexit referendum, she promised a stable government and enhanced powers for the Office for Budget Responsibility and the Treasury.

And plenty of evidence indeed points to post-Brexit volatility having a chilling effect on investment into the UK. But not all of the country’s economic woes can be traced back to the Conservatives’ internal power struggles.

Reeves also cited geopolitical instability – the rise of China, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the conflict in Gaza and the deepening climate crisis – as a further source of economic disruption.

She even highlighted her own party’s past errors. In a striking rebuke to New Labour, the shadow chancellor noted that Tony Blair and Gordon Brown had failed to tackle longstanding problems such as low productivity growth and regional inequality. Economic discontent, she argued, had fed the rise of the radical right, producing political instability.

Labour’s new answer to these challenges, Reeves continued, would be a modern form of industrial strategy, focused on resilience. Investment in domestic energy generation and infrastructure would help to shield the UK economy from volatility in global oil and gas markets, as well as assist the fight against climate change. Supply chains would also be restructured to reduce the UK’s exposure to geopolitical shocks.

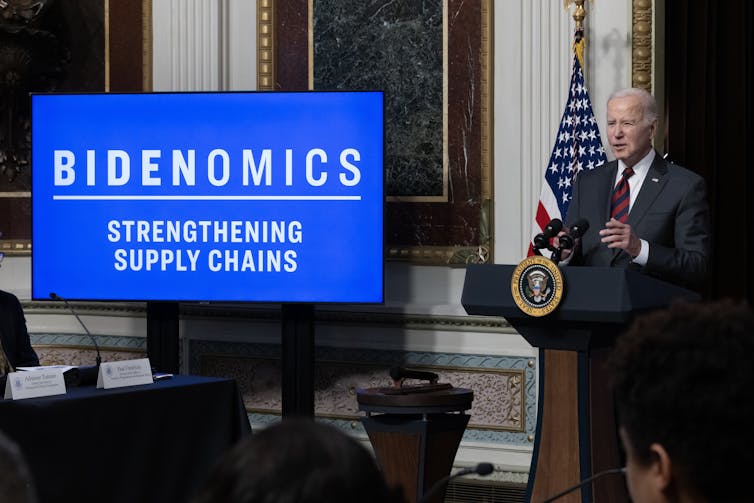

This is what Reeves means when she talks about “securonomics”, which is essentially an interventionist economic agenda of the kind seen recently in the US.

Since taking office, President Biden has significantly increased public spending on infrastructure and financial support for green energy generation. He has also sought to bring important industries, such as microchip manufacturing, back to US shores.

Reeves argues that it is cheaper to build resilience upfront than it is to bail out firms, households and public services when crises hit. And her claim seems plausible given the scale of (over)spending on medical procurement during the pandemic, the cost of subsidies to households and businesses following spikes in energy prices, and the increase in economic inactivity that has coincided with lengthening NHS waiting lists.

The shadow chancellor also argued that greater resilience would help to tackle the UK’s productivity problem. There is a wealth of evidence to suggest that people who feel economically secure are more likely to engage in innovation and entrepreneurship. Greater economic security can also improve the dynamism of labour markets by giving people the confidence to retrain, move jobs or switch careers.

But questions remain over how Reeves’s agenda will be delivered. Labour has repeatedly said that it will not raise taxes beyond some relatively minor changes, like imposing VAT on private school fees. Reeves is also keen to dispel any suggestion that she will increase borrowing levels (while emphasising that she views borrowing for investment as legitimate).

So with minimal extra money on offer, economic security must be achieved by using existing resources differently. Labour’s strategy leans heavily on the power of government to overcome coordination problems in the private sector and persuade businesses to invest collectively.

Governments can certainly do this to good effect, as recent research indicates. Countries such as Taiwan and South Korea are often held up as exemplars of this approach, helping to channel business investment into high-tech sectors with substantial export potential.

If Reeves’ analysis is correct, securonomics will eventually pay for itself. A more resilient economy will grow faster, provide more tax revenues to invest in industrial strategy and public services, and become more resilient still.

But it is not yet clear how Labour intends to set this virtuous circle in motion.

Slow and steady?

“Bidenomics” serves as a model for Labour, as the strength of the US economy demonstrates how industrial strategy can deliver growth.

But Biden’s interventions have been far larger in scale than anything the Labour party is proposing.

Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act alone cost US$500 billion (£397 billion) in public spending and targeted tax breaks. Labour’s current plans amount to an extra £4.7 billion of green investment per year.

Even after adjusting for the relative size of the UK economy, the difference in ambition is stark.

And despite Biden’s economic success, growth in the US may have come too late in the electoral cycle for the president to enjoy the political benefits. The instability of another Trump term remains a possibility.

The UK differs from the US in many ways, both economically and politically. But the US experience shows how, in an era of insecurity, time is of the essence. Implementing securonomics incrementally may prove to be a risky strategy for Labour – and for the UK economy.