Just For One Day, the Old Vic’s new musical about Live Aid, recreates the story behind the history-making concert in a spectacle full of iconic 1980s rock anthems.

The script may feel a bit clunky, but as it’s performed in front of enthusiastic audiences largely made up of people old enough to remember that warm July day in 1985, this is unlikely to be a sticking point.

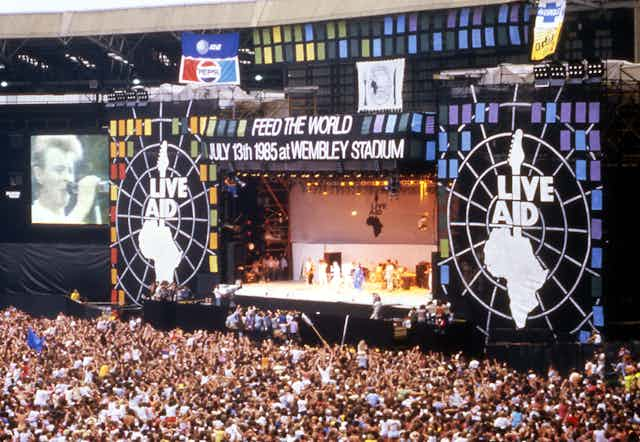

Rocks star Bob Geldof and the sometimes forgotten Midge Ure gathered together the biggest music acts of the time and persuaded them to play for free in concurrent concerts, one at London’s Wembley arena and one at the JFK stadium in Philadelphia. The idea was to raise money to help feed millions of starving people in northern Ethiopia which was being ravaged by drought and famine.

Those acts included David Bowie, Madonna, Bob Dylan, Queen, The Pretenders, Sade, U2, Diana Ross, Paul McCartney, Elton John and The Who, to name just a few. As the concerts beamed out to 150 countries around the globe, the money poured in, eventually raising US$140m (£114m).

Rather like Live Aid itself, the reviews for Just For One Day have been decidedly mixed. While the Telegraph enthused that “even the most hardened cynic will admire this rip-roaring retread”, and the Daily Express saw it as a “celebration and reminder of what human beings can achieve”, a rather withering Guardian review concludes it “piles homily on cliché in a production in thrall to white saviour stereotypes”. City AM goes one step further by slamming the production as “shockingly tone-deaf”.

But the fact remains that Live Aid was a global media spectacle. The event followed the success of Geldof’s Band Aid December 1984 single, Do They Know It’s Christmas?, recorded by a collective of largely British musical stars to raise money for Ethiopia.

It showed charities just how much celebrity involvement could raise the profile of particular disasters and causes – and it showed celebrities how charity work could boost their own profiles. What many in the third sector have ruminated over ever since are the benefits and problems this kind of celebrity association brings with it.

In the immediate aftermath of Live Aid, Geldof was lauded by left-wing thinkers such as Martin Jacques and Stuart Hall, who regarded it as a serious blow to what they saw as the prevailing Thatcherite ideology of selfishness.

But this was disputed, particularly by economics academic Robert Allen, who said that what Live Aid and its successors had created was in fact “the first truly effective version of Consumer Aid” – creating a product tailored to a specific consumer.

For those caught up in crises which capture a rock star’s attention, the effect can be astonishing. As the humanitarian Jan Egeland summed up not long after the 2004 tsunami, disaster victims can find themselves “in a kind of humanitarian sweepstake in which … every night 99% of them lose, and 1% win”.

Double-edged sword of celebrity activism

But what are the drawbacks of media coverage? In Just For One Day there are several scenes where tabloid hacks push Geldof to go to Ethiopia, or be pictured with a starving child.

This is the kind of imagery that critics of celebrity activism such as Tanja Mueller point out is “instrumental in establishing a … culture of humanitarianism in which moral responsibility towards impoverished parts of an imagined Africa is based on pity rather than the demand for justice”.

And while the present-day Gen Z character of Jemma in the musical describes Live Aid as “old white guys taking a day off from snorting cocaine to help Africa”, this criticism isn’t new.

In 1986, the anarchist punk band Chumbawumba released an album satirising rock stars’ charitable involvement called Pictures of Starving Children Sell Records. After 2005’s Live 8 concerts, an HMV music chart revealed that some of the bands taking part experienced a 1300% boost in album sales.

Yet scholars such as Andrew F. Cooper have been more positive about the idea of the celebrity activist, seeing them as bringing their chosen causes into a broader public domain and having access to key circles of power – what he calls the “Bono-isation” of diplomacy. Jubilee 2000, Live 8 and Live Earth all focused more on political change than fundraising.

But does using celebrities really help charities day to day? A survey of 2000 people found that while 95% of people could recognise five or more charities, two thirds could not name a single celebrity attached to them.

So why do charities, politicians and celebrities continue to work together? Perhaps because politicians like being around celebrities, and believe that they express populist sentiment. After all, the most constant double act in Just For One Day is not Geldof and any of the pop stars or even aid workers in Ethiopia, but Margaret Thatcher, with whom he shares several duets.

Changing the ‘pity’ approach

Things have changed since Live Aid albeit slowly. After criticisms around Comic Relief and the idea of “poverty tourism” that fed into notions of the “white saviour”, the BBC pledged to change the way it does celebrity appeals.

Many charities work hard with their celebrity advocates to ensure they know what they are talking about, unlike past cringeworthy efforts notably skewered in the Guardian’s Secret Diary of an Aid Worker.

And so where does this leave the Old Vic’s new musical? Well, if you’re someone who was at Live Aid or remembers watching it, it will undoubtedly conjure up all those feelings of excitement and being part of something bigger than yourself – the idea that we could be heroes.

If you’re part of the aid sector, the sense of ambivalence will probably remain: was it all just for one day?