Martyn Goff, the administrator of the Booker Prize, died aged 91 on Wednesday March 25. His somewhat bland title belies his central role in developing the prize into the global brand it is today, via canny networking and the occasional leak and stirring of controversies.

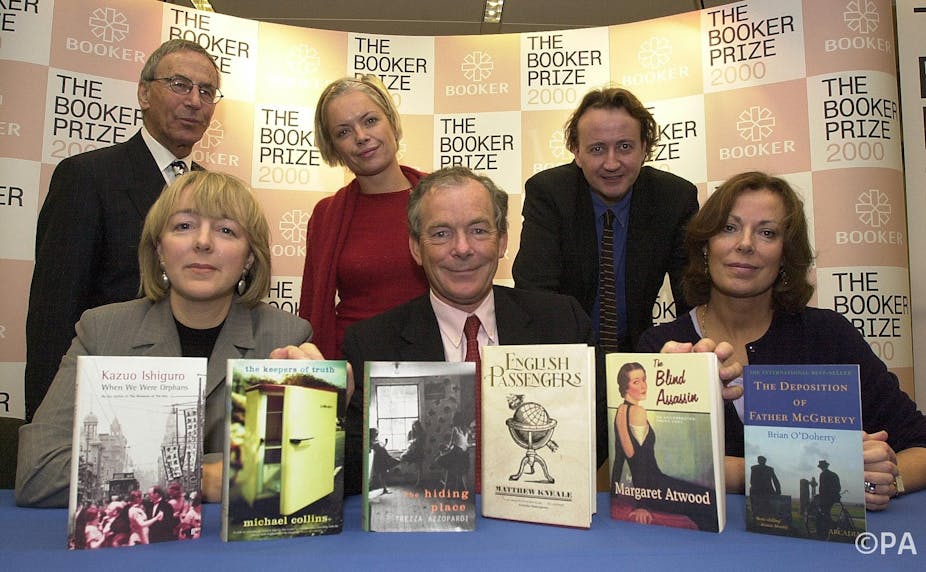

Nearly 50 years after their inception, the Man Booker Prizes are a global literary brand. Awarded annually since 1969, winners of the fiction prize include J M Coetzee, Pat Barker, Ben Okri, Margaret Atwood, James Kelman and Hilary Mantel. Winning and shortlisted books regularly see large sales uplifts, and university students have Booker books as set texts.

Most recently, the announcement of the Man Booker International Prize Finalists – a lifetime’s achievement award – has brought our attention to a diverse list of fiction writers from Argentina, the Lebanon, the Republic of Congo, and India, among others.

The brand portfolio also includes irregular awards for “The Booker of Bookers” and “The Best of the Booker” (both going to Salman Rushdie for Midnight’s Children), “The Lost Man Booker” (for books from 1970, which had been skipped due to an administrative change), and “The Man Booker Best of Beryl” (for Beryl Bainbridge, who was shortlisted five times but never won).

Being Mr Booker

These well-established, high-profile awards were an innovation in 1968, their future success far from assured. Martyn Goff was the awards’ administrator between 1970 and 2006, and had a key role in the story of Booker’s success. He was central in propelling the awards to their current heights, and has variously been referred to as the prize’s impresario, its maestro and its eminence grise. He was known in the book trade as Mr Booker.

As James English argues in The Economy of Prestige, cultural awards can perform a role in mediating between “cultural” and “economic capital”, which might otherwise seem in opposition – cultural works that have higher prestige are seen as less likely to succeed in the marketplace. Instead, English argues that prizes and awards contribute to “journalistic capital”. “Visibility, celebrity, scandal”, he explains, are core to journalistic capital – and can turn critical consecration into hard sales.

Martyn Goff excelled in the creation of “journalistic capital”. His background in bookselling, an instinct for book promotion and a canny sense of when to put a word in the ear of the press meant Goff was able to make the Booker front-page news. It was after Goff joined the Booker team that the awards stopped being awarded retrospectively. Judges began considering books from that year’s publications, making their deliberations more current and more useful in publishers’ and booksellers’ sales campaigns.

From the very beginning, the aim of the Booker Prize (as it was called until 2002, when a new sponsor appended “Man” to the title) was to promote and sell books, as well as to reward the “best”. Tom Maschler, publisher at Jonathan Cape, had witnessed the heady atmosphere of the literary prize season in France and wanted to bring excitement to British shores. Working with sponsors Booker McConnell (a food supply company), Maschler and the Publishers Association devised the first award, and its shortlist structure so that – as their press release put it – “the sort of speculation so beloved in France will be possible in Britain for the first time”.

Stirring

Of course, controversy is intrinsic to this sort of speculation. And Goff recognised this, as an early example shows. Shortly after he took over in 1971, Malcolm Muggeridge resigned as the chair of the judging panel. Some way through the judging process, Muggeridge sent a letter to the organising committee to say that he would have to resign because the vast majority of the books he’d been sent to read were “mere pornography” and had no redeeming features whatsoever.

The Booker Committee tried to hush up the resignation, but they were obliged to announce his resignation. The press release mildly explained that this was due to a “general lack of sympathy” with the titles, a phrase taken from Muggeridge’s letter. Some of the newspapers took the press release at face value. Others, however, had got hold of the real story, leading to salacious headlines in the Sun: “Muggeridge Quits in ‘Porn’ Row”; “St Mugg Quits in Porn Storm”.

It is widely believed that Martyn Goff tipped off the press, a judicious leak which put the Booker Prize on the front pages of the tabloid press.

He would go on in successive years to cultivate the media, to the point that every year there would be an expectation of some sort of quarrel, or at the least, very lively debate.

One of the few controversies that Goff didn’t have a hand in – indeed, was very unhappy with – was in 1972, when John Berger announced he would give his prize money to the Black Panthers, in protest at the sponsor’s historical connections to sugar plantations which ran on slave labour. The attack on the sponsor was, perhaps, one controversy too far.

Under its generous new sponsor from 2002, the well-established Man Booker has no longer needed to court scandal to get press attention, although the introduction of US writers to the prize from 2014 onwards reignited debate. In 2006 Goff retired from his role, but his legacy will long remain in Booker’s pre-eminence as a tool of literary recommendation and sales, which every year places its feted books into the hands of millions of readers worldwide.