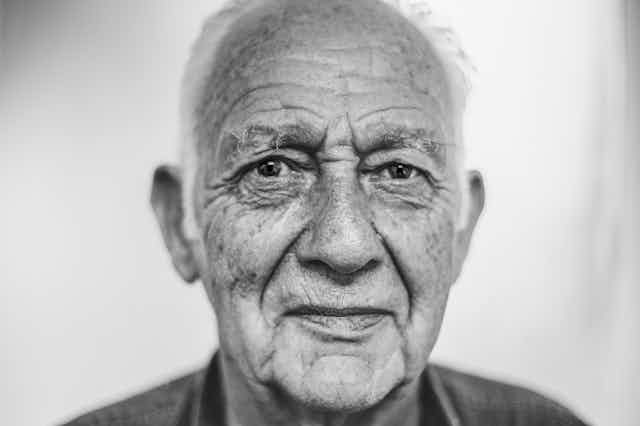

This article is part of our series on older people’s health. It looks at the changes and processes that occur in our body as we age, the conditions we’re more likely to suffer from and what we can do to prevent them.

In the 16th century, French philosopher Rene Descartes moved the body from the sacred to the profane by separating it from the mind. The body thus became a proper object of study by the emerging natural sciences. From anatomy flowed physiology and the birth of what we know as modern medicine. The model of the body as a machine which can be broken and therefore fixed has had great success, unimaginable only 100 years ago.

The problems with this model seem well understood, and are best explained in a landmark paper on suffering in medicine written 30 years ago. It points out bodies cannot suffer, only persons. A model with the body at the centre, focusing on the disease and how to get rid of it, fails to respond to the suffering of the person. Modern clinicians in this model do not see suffering as it is. We are merely the mechanics that fix the broken machine that is your body.

While this is admittedly a bleak, generalised view of modern medicine and some specialities such as general practice, geriatrics and palliative medicine do transcend this model, my experiences of hospital-based medicine give me reason to examine its effects.

I have always assumed older people were just like me, except older. As time goes on, fewer are older and more are younger. We all want the same things. Long productive lives, fulfilling relationships and to be able to do things. It is only as we age that we begin to understand the value of independence. It is invisible to the well and young.

Palliative medicine has shown me that people value their independence more than their lives. While discussions about death are often met with stoic indifference, rarely do people facing loss of independence remain unmoved.

Medical intervention in older people has the same aims as that in younger people. To cure, maintain or comfort. Being older just means you are more likely to have diseases already. Unfortunately, one of these diseases is frailty. Frailty is becoming increasingly recognised as its own entity. Currently there is no cure for frailty and ageing, as its cause cannot be prevented.

To be frail means you are much more likely to need help to do things. You are more likely to have a chronic disease and you are less likely to survive a serious disease. It also means the part about cure “at any cost” can have quite a cost. The burden of the treatment can outweigh the benefit, the risks of death or disability loom.

An ethical approach to medicine requires we obtain consent for interventions we propose. Informed consent implies that accurate information about prognosis can be communicated to the patient. This has proved elusive even for blunt measures, such as whether or not someone will live.

When it comes to the likely effect on independence, estimating the risk of functional decline for an older individual facing a serious event becomes an inexact science.

The difficulties become more apparent when viewed within the idea of the body as machine and doctor as mechanic. Seeing only the body and not the person leaves me with inexact probabilities as guides.

Cure at any cost means I am unable within my own mind to comprehend the effect on the person. The frenetic pace of the hospital environment denies me the time. Lack of life experience for a younger doctor makes many considerations invisible. Death aversion within medical culture colours consultations.

My work in a busy emergency department has taught me older people are indeed like the rest of us. They want to be seen, recognised as people and treated as adults. It’s easy to find out something about the person. They don’t want superhuman medicos. They want us to be honest and to be able to express uncertainty.

A greater part of the satisfaction I find in my work comes from helping older people confront what is in front of them, and helping them make decisions in the context of them as a person, not just the failing lumber of the body.

Read other articles in the series here.