The Netflix series Another Self, released in July 2022, is a drama / romance that tells the story of three friends living in Istanbul who travel to Ayvalik, a seaside town in the northwestern Aegean coast of Turkey, where they experience a life-changing journey.

One of the protagonists, Sevgi (Boncuk Yilmaz), has a cancer diagnosis. Sevgi attends a form of group therapy about connecting with ancestors, and for a time appears to get better.

Seen in some scenes of the show is the book It Didn’t Start With You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle by San Francisco-based author Mark Wolynn. Wolynn has thanked the show for including his book.

A theme in the show is some of the characters’ own skepticism about the role of ancestors in current suffering or problems, and their emerging exploration of this.

While we too should critically reflect when it comes to our health or popular advice about it, as a displaced scholar and as a historian of modern Turkey and its emergence from the Ottoman Empire, I never thought that watching a show would have such an impact on my way of thinking about events in Turkey that affected my family.

Great Population Exchange

The show spotlights problems affecting modern Turkey seen through different characters.

Following Sevgi, other main characters, Leyla (Seda Bakan) and Ada (Tuba Büyüküstün) also attend the group therapy. Throughout the series, we watch how an important trauma experienced in earlier generations — including events like earthquakes, political repression and sexual violence — affects their lives.

One of the main characters, Leyla, learns she inherited her fear of water from her great-grandmother, who was Greek with a Turkish husband living in Crete during the early 1920s.

The show depicts what is known as the Great Population Exchange between Turkey and Greece. This happened when the newly established Turkish republic signed a mutual exchange agreement with Greece in 1923 as a result of the Turkish War of Independence against the occupying allied forces between 1918-23. Due to the hostilities between Turkish and Greek forces, both countries decided to exchange populations in the aftermath of the war.

In the exchange, Leyla’s great-grandmother was left behind. Because she was Greek, she had to remain in Greece according to the Lausanne Peace Treaty signed between the two countries.

When she tried to illegally cross the sea to be united with her family, she was drowned by the Turkish boatman. This population exchange was not the first of its kind between Turkey and Greece.

Balkan Wars

In 1912, as a result of the Balkan Wars, Muslims and Turks living in the Balkans had to emigrate to Anatolia. My maternal grandparents were also among those Turks who had to leave their homeland in Thessaloniki (in present-day Greece) and emigrate to Izmir along the Anatolian coast.

The number of Turkish citizens whose ancestors emigrated from the Balkans in the early 20th century is estimated to be around 20 million today, which constitutes a quarter of the Turkish population.

Turkey’s problems related with internal migration and urbanization can be traced back to the early 20th century, and the important demographic transition experienced during the early years of the republic. With the trend of internal migration from rural to urban areas, Turkey experienced urban sprawl. At the same time, a lack of transportation, infrastructure, roads and housing caused slums to become widepsread in urban areas.

Cold War conflict

The character Sevgi believed since childhood she was at fault for her father being stabbed to death on her birthday. However, she learns from her mother her real father was a revolutionary who was shot at a meeting.

This context refers to how during the Cold War, Turkey was a hotbed of ideological conflict. Different leftist and rightist factions operated in the cities and universities, which caused polarization in society until the late 1990s.

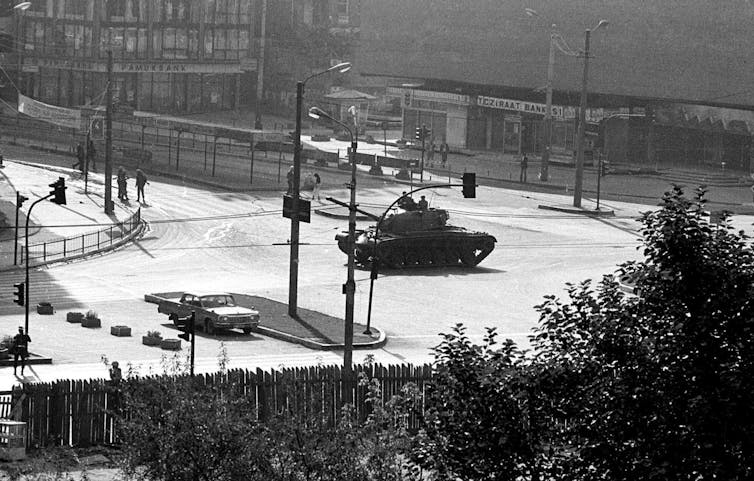

Following the 1980 military coup, the Turkish state implemented a strict policy against the leftist / revolutionary groups within the country. As a result of this, thousands of leftist intellectuals became political exiles in Europe. My maternal uncle, poet and activist Cengiz Dogu, was one of them.

As my research has examined in relationship to Turkey, authoritarian regimes and the oppression of intellectuals and dissidents ended with forced emigration of the educated masses out of the country. This meant Turkey was left in a cycle of underdevelopment.

Times of displacement

Through watching this show, both as a historian and as a displaced scholar, it occurred to me that my quest for academic freedom has, in a sense, duplicated a family tradition of trauma through displacement.

Maybe, in times of displacement, what we need is to acknowledge ties with our past and start a new life, just like the soundtrack of Another Self suggests.