Online polling is overhauling traditional phone polls, according to a New York Times analysis of the 2016 US presidential election campaign. Four years earlier, telephone surveys still had an edge of about four to one. But now online polls have almost caught up and are thought likely to overhaul telephone surveys by the next presidential campaign.

Beyond professional surveys, informal polls on news sites or social networks are everywhere – they engage online audiences and provide them, as well as politicians and the media, with an immediate snapshot of public opinion.

But commentators have raised concerns about online polls. Lack of representativeness is an obvious flaw for polls that only sample a specific audience. So, when NBC Sports in Philadelphia asked viewers about the best undefeated NFL team, the unsurprising winner with 96% of votes was the Philadelphia Eagles.

But it isn’t just biased audiences that can skew online polls. Some are susceptible to manipulation by bots. Worse, there exists a black market for buying online votes: a vote can be bought for less than two roubles (£0.03) on Russian online marketplaces. This allows individuals or organisations to easily fudge poll outcomes that can be used to influence citizens’ voting decisions.

Manipulated polls could also be used by companies such as Cambridge Analytica, who compile psychological profiles of individual citizens to run micro-targeted political campaigns. The company uses data from online quizzes and personality tests to build detailed profiles of individuals. It worked with the UK’s EU Leave campaign, which said:

Cambridge Analytica are world leaders in target voter messaging. They will be helping us map the British electorate and what they believe in, enabling us to better engage with voters. Cambridge Analytica’s psychographic methodology … is on another level of sophistication.

There have also been concerns about data protection issues and the ways in which this information might have been used – although there is no suggestion that Cambridge Analytica engaged in poll manipulation.

Manipulation of online surveys can be problematic in two ways. First, when many bots or paid respondents take part, it can change the results of the poll. Ideally, this dynamic can be tamed by robust technological authentication. But, more subtly, manipulation could also open the door to a phenomenon dubbed “cascades” by social scientists. By planting a few initial votes that make it look as if voters favour a particular outcome, manipulators could offset a dynamic that eventually shifts the poll result in the desired direction.

Majority appeal

But this thinking relies on competing assumptions about ways in which internet users are prone to social influence. On the one hand, out of a desire for conformity, it could be that individuals tend to shift their opinion towards what appears to be the average of the opinion distribution. On the other hand, they might just as easily be put off by the majority and adjust their opinions away from it.

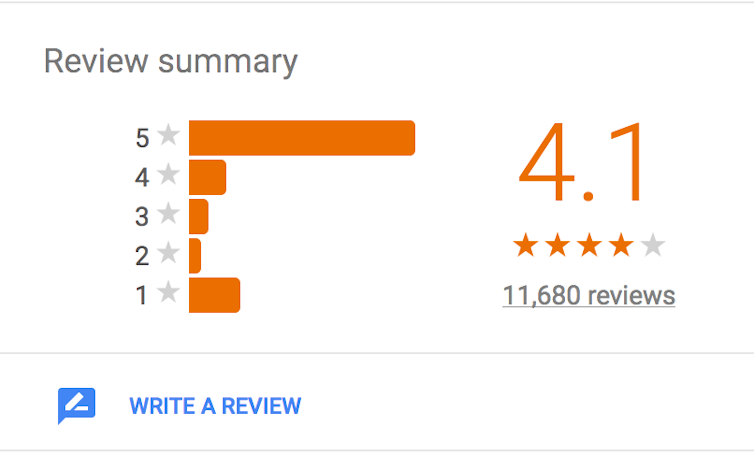

In a recent study, we tested how users state their opinions in an online poll after seeing other people’s opinions. We used data from an informal polling tool that displays previous votes before inviting a user to vote. The tool stacks votes into multiple bars. Here’s an example of this kind of poll in the context of product ratings.

Our questions ranged from general topics, such as Brexit or the US 2016 presidential election, to more specific questions such as the need of female quotas for recruiting pilots. The polls were embedded in real articles on British, American and German news sites, including the Huffington Post, The Times and Spiegel Online. Our study allowed us to estimate how users might change their opinion after seeing the opinions of others. Overall, we collected more than a million opinions.

We found that users were drawn towards the average of the opinions displayed online – typically, a user moves a bit less than half the distance towards the average opinion displayed. This seems like a substantial shift and would present a strong possibility for manipulation.

But the impact of the initial manipulation declines as more genuine opinions are collected. We found that this is because most users state opinions that are between the displayed average (which could be created through manipulation) and the “true average” – in other words, the average of users’ personal opinions. As our mathematical models show, eventually the average opinion converges to the true average, despite the strong social influence. This is bad news for manipulators.

But whether a poll converges from a manipulated average to the true average depends on the time the poll is active online. The shorter the poll runs for, the stronger the impact of initial manipulation. Also, the further away the fake votes are from the genuine votes, the more effective the manipulation. One important measure to prevent manipulation is thus to increase the time polls are online.

Opinion polarisation

Our results also give some perspective on the current debate about online polarisation. We’ve seen the way that users can be socially influenced towards the average of other people’s views. And because many people tend to visit news websites that publish news and opinions in accordance with their political views, results of any given poll on one site may tend to be homogeneous.

But overall, this can also mean that differences between opposing camps on any given issue can increase. To exploit this effect in order to intensify the differences between political camps, manipulators might use targeted messages in online social networks to lure users with opposite opinions to different polls.

This can lead to a questionable narrative if polling outcomes are presented as a significant body of opinion – think of the effect of the informal polls declaring Donald Trump the winner of the 2016 TV debate.

One solution might be to employ polling tools across websites and show users of any site the opinions of users from many different sites. This would create a poll of polls that aims to reflect opinion across the spectrum. There’s clearly a fair way to go before we can trust online polls to tell us about how people really feel.