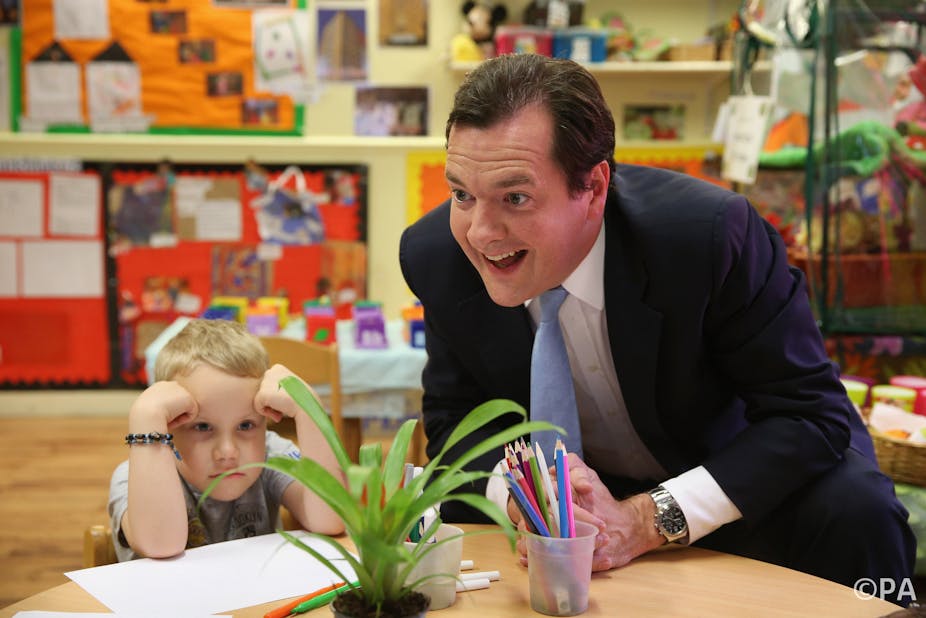

George Osborne’s impromptu child-minding of shadow chancellor Ed Balls during pre-budget interviews summed up his task in the last full year before the election as effectively as Wednesday’s budget speech.

Put simply, the chancellor must convince the increasing number of dual-earner families that the new childcare subsidy is part of a strategy for ensuring that their work commitments pay. At the same time he must also reassure stay-at-home parents that they are included in the clichéd praise for “hard-working families”.

He must persuade all middle-income earners that the government has helped them during the long wait for economic recovery. Here, the hope is that increases in the personal income tax allowance (to £10,500 from April 2015) will outweigh the effects of inflation that has “fiscally dragged” 1.4m people into the 40% tax bracket and deprived them of child benefit when they hit that higher rate.

Most poignantly, Osborne’s helping hand to Balls Jr symbolised his promise to today’s children that he is rescuing them from a mortgaged and growth-constrained future, by arresting the rise in national debt. The coalition’s lapse from his original timetable for balancing the budget has been turned into a reason for re-electing it, to finish the job of defusing the “debt bomb”.

The latest Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts, released on budget day, point to balance being almost another parliamentary term away. Despite the return to growth having been delayed almost three years, the economy is already closer to full capacity than the OBR and Treasury originally anticipated. But this means less additional revenue is set to flow as growth quickens over the next few years, so more of the remaining deficit reduction will have to come from further spending cuts or tax rises.

As a result, the present government has already borrowed more in its first three years (£267.4 billion) than the previous government did in the preceding three (£243.3 billion), at a time when the global financial crisis was at its worst. Osborne is on course to be the chancellor who added more to public debt than any other, lifting the net debt to 79% of GDP in 2015/16.

With this year’s deficit almost twice the 2010 target, the recovery has been more reliant on “automatic stabilisers” – the rise in obligatory payouts during recession – than anyone at the treasury would like to admit.

In any case, the idea that the UK’s public deficits and debt of 2010 were unsustainable, going above levels that it could grow its way out of, has taken a battering during Osborne’s time in office. The effectiveness of budget deficits in restoring growth when an over-borrowed private sector is forced into saving has been shown to be much more powerful than the chancellor’s advisers believed in 2010. Evidence that public debt – even at 90% of GDP – starts to restrain the rate of growth was found to have been exaggerated by arithmetical error and a questionable data set.

Backhanded compliments to these “Keynesian” rediscoveries abound in the subtext of the budget, which is one of prolonging the public deficit to help the private-sector borrowing that has driven the recovery to date.

This is evident across several different policies. The extension until 2020 of the Help to Buy mortgage subsidy and the raising of stamp-duty thresholds seeks to stoke the housing market; funding-for-lending aims to mobilise small-firm credit; and a further drop in corporation tax towards 20% plus temporary doubling of capital allowances and export credits looks to get more large firms investing their precautionary cash piles.

The danger is that it’s private-sector debt, already much larger than the public sector’s (more than 150% of GDP even when the banks and shadow-banks are excluded), that may have jumped back above safe levels under this Chancellor. For all his child-related charity, that’s an awkward parcel in his successor’s privatised post.