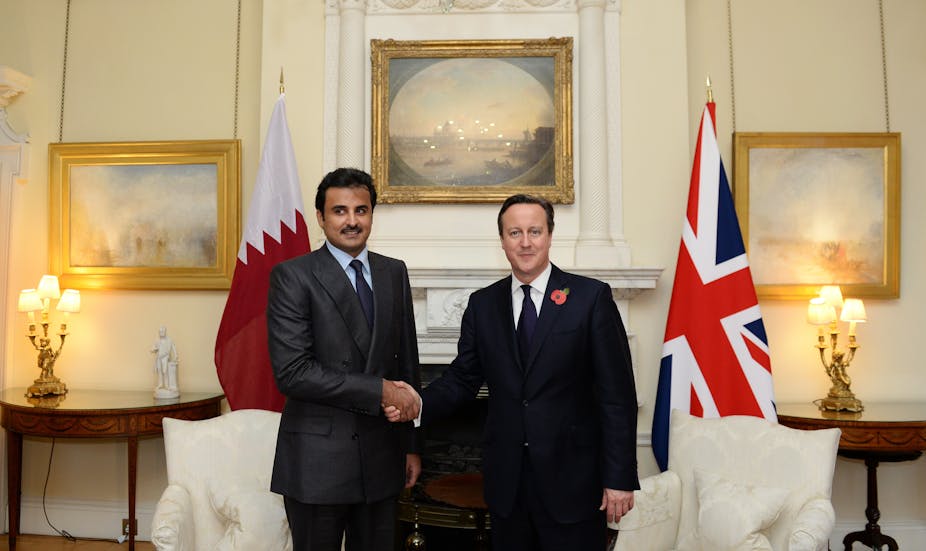

During his October visit to the UK, Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al Thani had to fight to convince the British government that Qatar stands firmly against Islamic State (IS). Despite his efforts, media reports of Qatar’s alleged support for dangerous jihadist groups go on.

The reasons why are clear enough. In Qatar, the global media has found a perfect scapegoat for the world’s failure to contain the growth of IS: a fabulously wealthy Islamic monarchy, many of whose citizens have ample funds to distribute around the region as they see fit. But the claim that Qatar has been financially supporting IS or its predecessors is not founded on any concrete evidence.

Straighten up

While some wealthy Qataris have privately funded IS’s predecessors in Iraq and Syria, the state of Qatar has not done so. Its leaders know IS stands in stark opposition to both Qatar’s national interest and its Syria policy. Supporting a transnational or even global jihadist organisation such as IS, which violently rejects the Middle East’s status quo, would be ideological and practical suicide.

Qatar has been involved in Syria since 2011, when Bashar al-Assad refused its former emir’s exhortation to resign and give way to political reforms. Since the beginning of the crisis, Qatar has been interested in bringing about a sustainable settlement in Syria – creating an inclusive political system in a country too long ruled by sectarianism.

Qatar’s support for moderate Syrian Islamist groups, such as those gathered under the banner of the Islamic Front, has always been based on the same pragmatism: the idea is to fund groups with the organisational ambition and infrastructure not only to engage regime forces effectively, but also to mobilise a local social base in an effort to create a new order.

And alongside the main realpolitik aim to transform financial wealth into political influence, Qatar’s foreign policy in Syria has also been guided by a reasonable degree of altruism. That’s why it has been supporting local Syrian groups able to provide public goods to Syrian people on an inclusive basis. The groups Qatar deemed moderate enough to support consisted predominately of local Syrian fighters fighting for a just order in a post-Assad Syria.

Operating in extreme circumstances of violence, despair and deprivation, these groups were the Arab world’s most prominent counter-narrative to state-sponsored repressive tyranny. They were neither al-Qaeda-esque jihadists pursuing a global jihad, nor thugs abusing Islam to brutally further the utopian idea of a Caliphate against the people’s will.

IS, on the other hand, is neither catering for the good of the masses nor helping locals free their homelands from oppression. Instead, it’s a multi-layered group of fanatic, extremist mercenaries, employing desperate locals who are either coerced into joining the self-proclaimed mujahideen or do so voluntarily in an effort to further their own non-ideological interests.

Building a bridge

Considering that IS has received ideological and financial support from various private donors in the region and continues to recruit from around the world (particularly from the West), Qatar’s role in the evolution of IS is in no way exceptional.

And we should by no means ignore the role external funding has played in IS’s spectacular growth. Ever since 2004, when IS’s predecessor group the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) was created, it has worked hard to stay financially self-sufficient – an ambition that has become a lot easier since IS controls an area as big as the UK, complete with millions of inhabitants, oil wells, refineries, cash reserves, and the riches of thousands of years of cultural heritage.

IS’s economy of extortion does not only extract rents from those living under its occupation, but also revolves around the illicit trade of oil products and antiquities. Consequently, the self-declared “Caliphate” can generate millions of dollars a day without having to rely on sporadic illicit donations from private individuals, in Qatar or elsewhere.

Ultimately, the IS problem is part of a bigger regional challenge: there can be no security until the marginalised and disenfranchised masses in Syria and Iraq live in sustainable states founded on social justice. The anti-IS coalition of which Qatar is part will only play a marginal role in defeating this vile caricature of the once mighty Caliphate.

Qatar supports the Saudi-American plan to train and equip a sufficiently capable force of more than 10,000 Syrian rebels, and its participation could be decisive for the plan’s success. Qatar’s established links with moderate Islamist groups can help with the recruitment of sufficient numbers of battle-hardened fighters, many of whom, while certainly Islamists, would welcome a united and inclusive Syrian state.

The plan will not work if the states fighting IS continue to ignore the moderate Islamist groups who united under the banner of the Islamic Front – and Qatar is the bridge to those groups. So instead of lazy Qatar-bashing, the West should think about how to constructively engage with Qatar as a potential partner, not only in the fight against IS but also in a long-term political solution for the whole Middle East.