You’re driving somewhere remote at night, and out of nowhere, a deer dashes onto the road and makes it across just inches ahead of your bumper. Anyone who owns a car is likely to experience this at some point.

Most of the world’s land is intersected by roads, and they break natural habitat into isolated patches and endanger the lives of animals who try to move between them. The relatively small country of Denmark, for example, is covered by around 59,000km of paved roads, on which over 2.5 million registered cars drive.

An estimated 194 million birds and 29 million mammals die each year on European roads. Apart from causing unnecessary death and suffering which might ultimately reduce populations, animal-vehicle collisions also risk human safety and cost drivers and insurance companies dearly, especially when larger animals are involved.

The good news is that something can be done about this, because the risky road crossings that animals attempt do not happen randomly. In a new study, we found that the timing and location of collisions between wildlife and vehicles are actually fairly predictable. We can use this information to create warning systems that help drivers to be more vigilant.

Wildlife crossings

In other studies, researchers have tried to find hotspots in the landscape where most animals tend to cross roads. These areas can then be fenced off and bridges and tunnels built to allow wildlife to bypass the road safely. These measures reduce roadkill and help animals roam more freely, whether it’s to continue on ancient feeding migrations or to seek mates and reproduce.

Sadly, creating wildlife crossings is very expensive, and rarely cost-effective over large areas and all road types. This is especially true in densely populated countries with lots of roads like the UK, Germany or Denmark. Just adding fences along roads would be the cheaper alternative, but if there are no corridors to allow animals to keep moving, fences would only keep animals isolated from each other.

The traditional approach to reducing roadkill in most countries is to use wildlife warning signs. But since these road signs remain fixed in one place, they are not very effective. For example, deer won’t usually cross a road during the middle of the day when more drivers are likely to be on the road. Animals are active at specific times and might use different areas depending on the time of year. Road signs most often warn drivers when the risk of animals crossing is relatively low, and as a result, drivers pay less attention to them over time.

A warning app

We investigated 85,000 vehicle collisions in Denmark for three species – roe, fallow, and red deer – over 17 years. Both the place and the time at which collisions happened were predictable and largely similar between the different deer species. More collisions occurred during dusk and dawn, when traffic levels were intermediate, and in areas when forest cover was increasing.

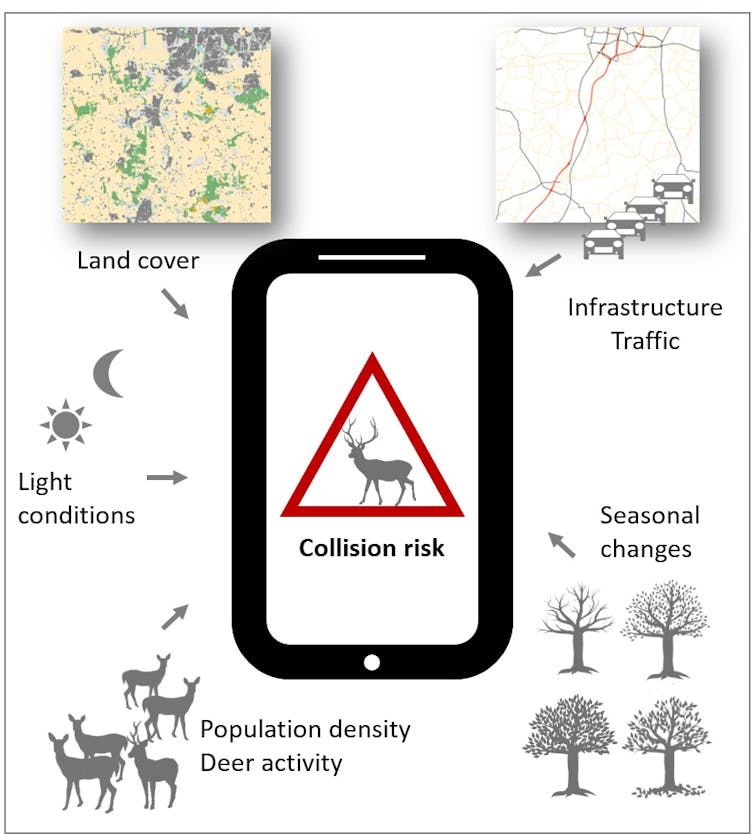

These findings could feed into digital maps and sat-nav to create a live warning system that updates drivers when they’re passing through high-risk areas at times of the day when lots of animals are active. A noise or flashing signal could alert drivers when a collision is likely.

Many of the factors that help predict the risk of collisions on roads, such as land cover, road type and traffic volume, are already recorded in digital mapping systems. Information on deer population density and activity, from projects that collect this kind of data, could be added.

Users could even report collisions to make the app more accurate. Such reporting systems are already used in some countries, like Sweden, and via some apps, though they only map the place, and not the time, where roadkill happened.

Of course, this warning system will not be as efficient in reducing roadkill as fencing and wildlife passages. But it would be a far cheaper alternative in places where these other measures are too expensive or difficult to implement. Even if it helps reduce roadkill by as little as 10%, it would still save the lives of tens of thousands of people and animals in Europe each year.