It has been nearly 100 years since the skeletonised remains of nine people were removed from their graves on a farm near the town of Sutherland in South Africa’s Northern Cape province. They were donated to the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) anatomy department by Carel Gert Coetzee, who had unearthed them and was a medical student at the university.

The remains belonged to San and Khoekhoe people, two groups indigenous to South Africa. Their families were not consulted about the removal and donation.

This, sadly, was not unusual for the time. Anatomy departments and museums around the world collected human skeletal remains during the colonial era and into the first half of the 20th century. They were displayed in museums or studied for scientific purposes, often with a racial lens depicting indigenous people as primitive and inferior.

Read more: Science and race in South Africa: lessons from 'old bones in boxes'

I am an associate professor in what is today the Division of Clinical Anatomy and Biological Anthropology. In 2017, after encouragement by other museums and universities in South Africa, I completed an archival record review with the aim to identify remains that had been unethically obtained. That was when I came across the Sutherland collection; and immediately realised that, as UCT, we had a moral and ethical duty to return them to their community.

A public participation advisor Doreen Februarie was appointed to approach the community. Myself and UCT’s senior leadership represented by DVC Professor Loretta Feris thought they would merely request the return of the remains for reburial. They did – but first, the descendent families asked the university to study the remains with a view to learning more about their ancestors’ lives.

We recently presented those research results in a single, large, multi-authored publication.

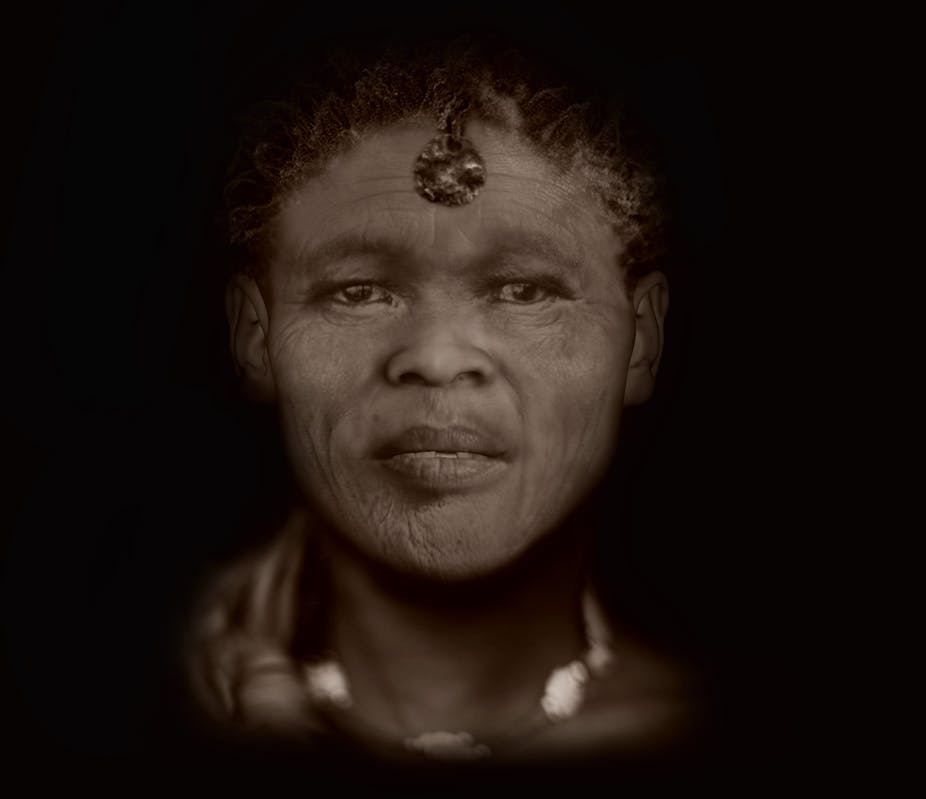

We traced historical records, conducted archaeological field work, analysed the physical remains and conducted biomolecular analyses. Facial reconstructions were completed for eight of the nine people – now known as the Sutherland Nine.

The Sutherland example may set a global precedent for a process of restitution and restorative justice in combination with community-driven science. My hope is that more curators and custodians of human skeletal remains elsewhere in the world will attempt to redress some of the wrongs of the past.

Beginning the process

To ensure that we reached the right people in Sutherland, a public participation advisor was chosen to lead a process with the community. By then, I had studied the archival records related to the donation; these revealed names and two surnames. The community elected those carrying the same surnames as their representatives.

People were shocked and dismayed at the situation. But they also wanted to know who the nine had been and how their remains came to be at the university.

Our answers were limited. When I realised in 2017 that they had been unethically obtained, the department placed a moratorium on studying them. The community requested that this be lifted: they wanted the remains studied to understand the people and the situation. Once this was done they wanted the remains returned so the nine could be reburied properly.

As our research unfolded, we decided to present the results in a single publication. The more common approach would have been to publish several individual papers, focusing on the science. We decided instead to tell the story of the Nine with science as the background.

Read more: Why scholars have created global guidelines for ancient DNA research

We obtained informed consent from the community at every step of the process. The family members wrote in their own words what research they wanted and why, along with their restrictions on data use. For instance, they didn’t want any photos of the actual bones to be published – only digital renderings could be used. They also asked that the DNA sequences obtained from each of the Nine be kept private after scientific verification through peer review. And if anyone wants to conduct future research they must approach the families to begin a new process.

The families of the nine were also asked whether they wanted to be listed as authors in the eventual publications. Collectively, they chose formal acknowledgement in lieu of authorship.

Hard lives

It is impossible to summarise all our research findings here. Overall, though, we found that life was physically hard and violent for the Sutherland Nine. One died as recently as 1913; the remaining seven died in the 1870s or 1880s.

When the late professor of anatomy MR Drennan took delivery of the remains in the 1920s, he also noted what little the donor knew about the people’s lives. Most adults were identified by first names (Cornelius, Klaas, Saartje, Jannetje, Voetje, Totje). For two, surnames were also specified – Cornelius Abraham and Klaas Stuurman.

The descendent families have collaborated with the National San Council to rename the unnamed individuals.

The younger boy child (four to six years of age) has been named G!ae, from the N/uu language; it translates to “springbok” – an animal symbolising the San’s pride in their culture and future prosperity. The older girl child (six to eight years of age) has been named Saa, which translates to “eland”, a sacred and spiritual animal in San culture.

The ninth individual did not live at the same time as the others. He was an unnamed adult said by the donor to have been buried 40 years earlier near Sutherland, although the precise burial location was unrecorded. We used radiocarbon dating to show that he actually died about 700 years ago.

There is no evidence that this individual was directly related to the other eight, but his remains came to the institution from the same donor. He has been named Igue We, meaning “blessing”, to symbolise acceptance and blessing by San ancestors for his reburial.

Painful legacy

The principal message of this collaborative approach is how community-driven research can benefit processes of restitution when grappling with painful legacy collections.

The reburial of the remains in Sutherland is likely to take place later this year, though no date has yet been set.