In 1859, from August 28 to September 2, we were given an important lesson about how vulnerable we are to the Sun’s power. The Carrington Event, named for the amateur astronomer who recorded it, Richard Christopher Carrington, was a coronal mass ejection: a huge burst of solar wind. When this solar storm hit the Earth’s magnetic field it caused an aurora so bright it could be seen as far south as the Caribbean and Hawaii. But the novelty of being able to read a newspaper by this eerie light was not the only effect caused by the arrival of the storm.

One of the least reported impacts of the 1859 solar storm was the massive disruption it caused to the telegraph systems across Europe and North America. Telegraph operators were said to have been shocked by their equipment while telegraph poles threw off sparks. The amount of power delivered by the storm was so great that some telegraph operators were able to disconnect their power supplies and still send messages.

Roll forward to today and consider how much more dependent we are on communications. In 1859, telegraphs were the height of innovation. Now practically every business in the country relies on electronic technology to some extent. Much of our working life is spent sending and receiving emails and our social lives exist increasingly online. We store important personal information on our computers and depend more and more on internet services to complete everyday tasks like our shopping and finances. So imagine if the internet started throwing off sparks of its own.

Thankfully, much of the internet uses fibre optic cables and would be protected from a solar storm on the scale of the Carrington Event. But local distribution is still done using old fashioned copper cabling. This is exactly the sort of network that is vulnerable to space weather. In March 1989 a solar storm hit the Quebec Hydro Electricity network, disrupting the entire region. The degree of disruption obviously depends on the intensity, duration and location of a solar storm hitting the earth. But, should something such as the Carrington Event occur today it would have a serious impact on the Earth’s communication and power systems, which in turn would have an inevitable impact of the economic activities of those affected.

Today we have a further complication. We use a very sensitive form of equipment that didn’t exist in 1859 and was not widespread in 1989: computers. Modern electronics are so delicate that a burst of intense magnetic activity can easily disrupt them. This is why the cold war saw the emergence of “electromagnetic pulse” weapons, which were specifically designed to “kill” electronics, such as computers. But, as ever, nature can do much worse.

The range of vulnerable equipment is broader than many people realise. Computers are no longer the grey boxes on our laps or under our desks. They are embedded in many everyday systems from traffic lights, cars, water treatment plants, power stations and just about any other industrial situation you can imagine. If these were disabled it doesn’t take much to visualise the impact.

Then there are the GPS and telecoms systems that live on satellites, unprotected by the Earth’s atmosphere. These are vulnerable to relatively minor solar storms and could leave us without vital services if hit.

While the impact of a major solar storm could be significant, the likelihood of it occurring is far less easy to determine. Predicting space weather is as difficult, if not more so, than terrestrial weather. We have satellites such as SOHO to monitor ejections from the Sun, but even if we saw an ejection we would have a relatively short time before we felt its impact.

It might help to determine which regions are most vulnerable but even then, our ability to protect the numerous pieces of electronic equipment that might be affected would be limited. Turning the equipment off might be the only protection we have, and this is no guarantee of avoiding damage. The act of turning equipment may itself have a significant economic impact.

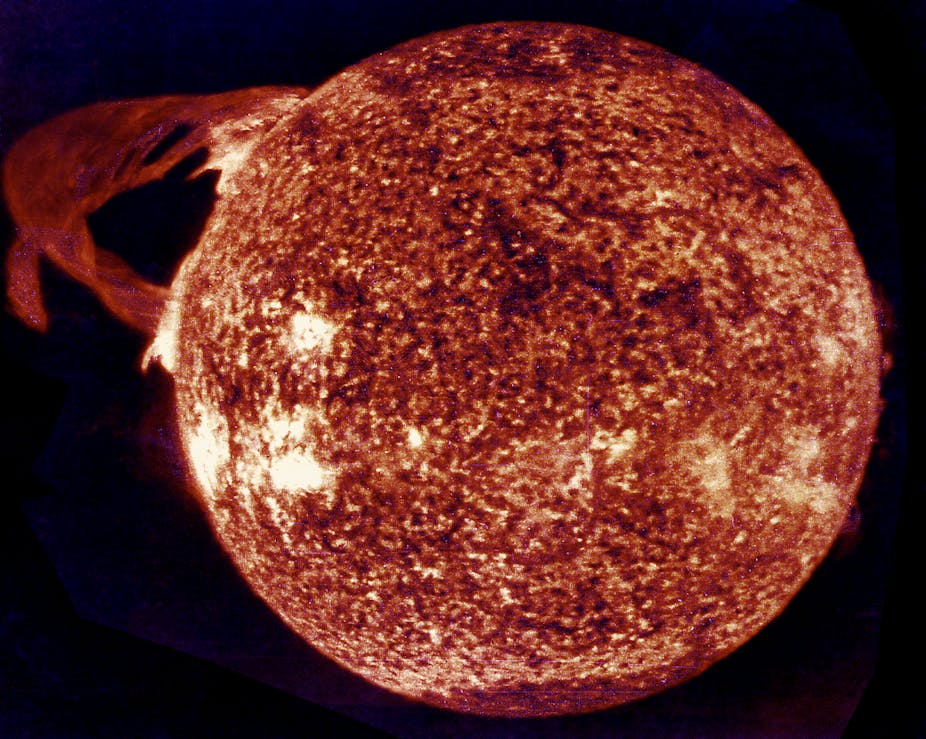

During the Sun’s 11-year cycles, sunspot activity and the amount of material ejected varies. For this to matter to us, the Earth has to be in the line of fire of an ejection. SOHO has witnessed many large ejections but these have all being heading in a direction other than the Earth. What we need is some level of understanding of how often coronal mass ejections of a significant size hit the Earth.

One source of information we have is that gained from analyses of ice cores taken from Iceland. This seems to show that events such as 1859’s solar flare only occur every 500 years. However, events of up to 20% of the power of the Carrington Event occur several times per century. That suggests that while we may not see an 1859-type event in our lifetimes, there is still potential for isolated regions to be affected. Perhaps this is what we saw with the Quebec incident in 1989. We also know that similar events took place in 1921 and 1960.

All things considered, the Carrington Event seems to be classifiable as a “Black Swan” event: something that is very unlikely to occur but would have a serious impact if it did. Even with the increasing amount of solar activity that we are seeing during 2013, the likelihood of Earth experiencing a major event is low.

The government is waking up to the need to be prepared as much as possible for these events and has added solar monitoring to the Met Office’s responsibilities. It is also acting on a recommendation by the Royal Academy of Engineering that a space weather board be established to lead efforts to prepare for the worst.

That said, we are, perhaps, better focused on more immediate risks: ones that we can actually mitigate. Consider the threat posed by cyber-attacks and how they disrupt our communications and computers. We can take basic precautions to deflect up to 80% of these attacks. When it comes to the power and unpredictability of the Sun, we are about as exposed as we were in 1859 and there’s not much we can do about it.