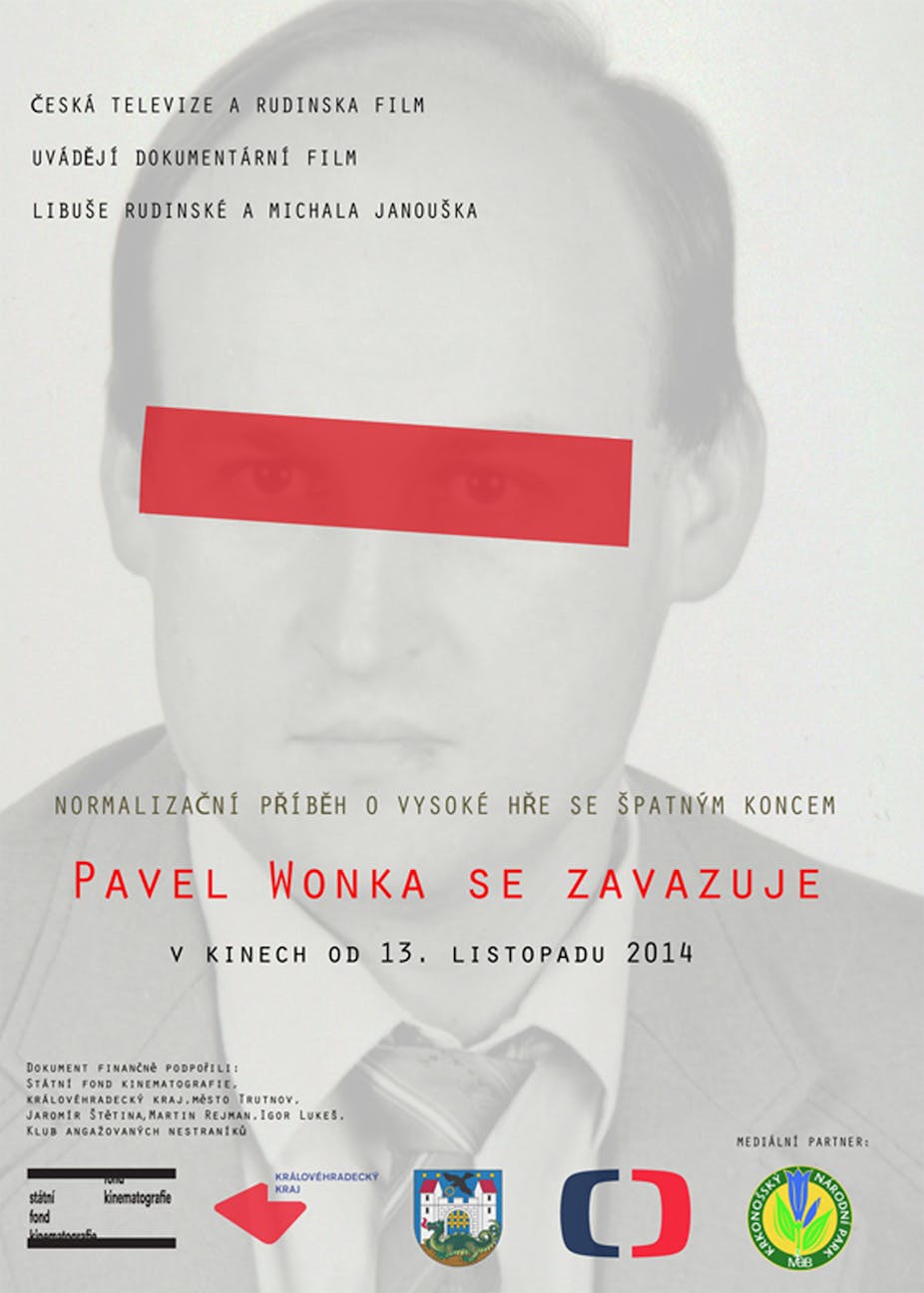

The release of a documentary film in the Czech Republic earlier this year caused much controversy. It is about a dissident named Pavel Wonka who fought against the totalitarian regime in Communist Czechoslovakia. What has caused the filmmaker, Libuse Rudinska, to be the target of much criticism is that she does not portray the man who died while on a hunger strike in prison as a pure angel.

Heroes are scarce in modern history. Every hint of civic courage, it seems, needs to be treated with the reverence that was once reserved for holy relics. When evidence appears that casts doubt on a hero’s image, admirers find it difficult to accept. And yet the list of heroic individuals who changed their countries and who – at the same time - betrayed them is not a short one.

The count turned revolutionary

Let’s start in the 18th century, with the case of Comte de Mirabeau. Born in an aristocratic family, he became one of the leaders of the French Revolution. He celebrated the Third Estate – or France’s common citizens – and attacked the royal privileges with passion and eloquence. But when in 1790 the Austrian ambassador in Paris invited him to become a secret “advisor” of Louis XVI, Mirabeau accepted without hesitation. It flattered him and he needed the money.

Mirabeau’s confidential service for the besieged monarch did not slow down his public career on behalf of the Republic. He was elected president of the National Assembly and when he died, his fellow revolutionaries celebrated his achievements by making him the first Frenchman to be interred in the Panthéon, the country’s mausoleum. Then came the shock. Documents were discovered indicating that Mirabeau, the great revolutionary, had been a paid agent of the king. His remains were removed from the Panthéon and dumped at an unknown location.

Who was Mirabeau? A hero of the revolution or its betrayer?

A priest and a secret agent

An even more dramatic ending awaited the Russian Orthodox priest Georgy Gapon. Having graduated from the seminary in 1902, Gapon became active in progressive circles in St. Petersburg, where he attracted the attention of the secret police. Its agents recruited Gapon without difficulties. He needed money and liked to be at the center of events.

Although his role of an informer was defined clearly, Gapon never thought of himself as a passive instrument of the police. He demonstrated his independence during Bloody Sunday in 1905, when he emerged as the leader of a procession that tried to present a petition to the Tsar. It was a miracle he survived when soldiers fired at the marchers. Overnight Gapon became a celebrity, a respected champion of liberty. Among his admirers were Vladimir Lenin, the writer Maxim Gorky, and the French politician and future premier Georges Clemenceau. They, naturally, had no idea that their hero was a police agent.

Gapon finally overplayed his hand when he tried to recruit another radical as a police spy. The man handed him to an underground tribunal that hanged him on the spot. The revolutionaries executed Gapon for treason, yet the image of a priest, standing Christ-like between the soldiers and the masses, improved their cause in Russia immensely.

Working class leader

Then there is Poland’s Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Solidarity movement against his country’s communist regime. It was Walesa who, together with John Paul II, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Ronald Reagan, helped write the history of the eighties. This Nobel Prize winner is celebrated in the West but is a divisive personality in Poland. Records from the archives indicate that Wałęsa was a secret police informer from 1970 to 1976. Consequently some Poles have denounced him, while others have attacked the evidence as forged. Wałęsa himself denies the claims.

A secret service that falsifies its own archives cannot function. There is little doubt in my mind that Wałęsa, under pressure, signed an agreement to act as a police informer. Like Mirabeau and Gapon, Wałęsa fought against the dictatorship but was also – at least for six years before the birth of the Solidarity movement – its paid agent.

The real question, however, is this: where does his real contribution lie? On the side of free Poland, or the side of the agents who broke their prisoner during an all-night interrogation? That question is best answered by noting that Poland is now in the EU and NATO.

Spying for both sides

Consider, too, the twisted case of General Dmitry Polyakov. This officer of Soviet military intelligence (GRU) offered his services to the Americans at the end of the fifties and worked on their behalf for 24 years. In 1980 Polyakov was recalled to Moscow, where he disappeared. It later transpired that he was arrested in 1986 and executed two years later.

This could be dismissed as a banal case of Cold War espionage. It is not. It recently turned out that the GRU dangled Polyakov to the FBI and CIA to spoof them with fake intelligence. His job was to lure the Americans into a disinformation game, and Polyakov did this for years. Then, at some point, he decided to switch sides and supply the Americans with true intelligence. The Russians eventually found out that the man they had sent to deceive the Americans was cheating them. When they confirmed it, Polyakov was shot.

As he faced his executioner, was Polyakov a Soviet officer who had for years misled US intelligence, or was he a CIA agent who had helped to win the Cold War?

The political prisoner

And now back to the Czech Republic and the Pavel Wonka case. Wonka was born in Communist Czechoslovakia. He generated international headlines in 1986 when he decided to run for a seat in the National Assembly – this was legal but highly provocative because the Communist Party had a monopoly on politics.

The regime responded by brutally mistreating Wonka who died in 1988 on the floor of his prison cell, weighing 88 lbs. His funeral, attended by prominent Western diplomats, energized Czech dissidents and, arguably, gave an impetus to those who carried out the Velvet Revolution the next year.

When the Prague archives were opened in the 1990s, it came to light that Wonka had agreed in 1983, previous to his fame, to become a police informer. To mention this fact in today’s Prague – especially in a full length documentary movie – causes many to cry in protest. They see it as dancing on their hero’s grave and giving undue credibility to the records of the secret police.

It is, in my view, the wrong reaction.

In spite of the commitment that the agents had earlier wrested from him, he had the guts three years later to reveal the phoniness of the Communist system by seeking to run in the “elections.” It took great courage for Wonka to die in prison, rather than claim advantages for himself as a police collaborator.

What, then, do all these men have in common?

Mirabeau, Gapon, Wałęsa, Polyakov, and Wonka became involved in clandestine activities but they never intended to surrender their moral autonomy and values. Their secret commitments notwithstanding, they believed that they would be able to play important quasi-diplomatic roles.

Mirabeau hoped to blunt the radicalism of the revolution. Gapon thought the Tsar needed to find out how people lived outside his palace. Wałęsa advocated compromise between the strikers and the state in critical moments. Polyakov thought that by working for East and West he helped to save the world from the danger of nuclear war. And Wonka tried to get involved in the politics of a totalitarian state not because he was a naïf or a moral exhibitionist but because he believed that the government was inept, divorced from reality, and needed help.

Yearning for a world inhabited by heroes and villains is a natural defensive reaction to the surrounding chaos. This is why, on close examination, public personalities tend to disappoint us since they fail to fit in the black-and-white categories we prefer. They “disappoint” because they can plausibly function on both sides of fault-lines that others consider unbridgeable.