Everyone along the street seemed to be watching the same thing. The evenings were still light and curtains were not yet drawn, so people’s TV sets were visible through their ground-floor windows. All the screens showed the burning Twin Towers. This mass consumption of the same news – as happened on September 11, 2001 – is rarer now. The ever-multiplying number of media platforms continues to fracture the attention of their audiences.

Back then, I was on my way back to my flat in Brussels to pack for a flight across the Atlantic. Two days later, I was able to fly to Montreal and travel from there to Manhattan to cover the aftermath of the attacks. It was while I was there that George W Bush warned the nations of the world: “Either you are with us or you are with the terrorists.”

This remark may not have been aimed at journalists in particular. The best reporting, however, often leaves room for a degree of interpretation – “with us, or against us” does not. One of journalism’s roles in a democracy is to speak the truth to power, not simply accept power’s rules.

I was reminded of this when I heard the experienced foreign correspondent Peter Greste reflect on the 400 days he had spent in jail in Egypt after being arrested there on trumped-up charges. Speaking last October, as he presented the Kurt Schork awards in International Journalism at Reuters, he said:

You know generally when you push the boundary. You know generally when you work when you’ve done something that might upset somebody – someone in government, some administration some way so I was completely taken aback because we hadn’t done anything that was pushing any boundaries.

Greste linked his fate to the way that the world had changed for journalists since September 11. Increasingly, they were not seen as neutral observers – and, as a consequence, were not treated as such.

Mobilising opinion

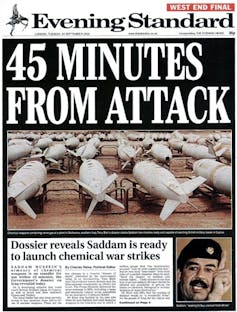

Journalists have greater responsibilities in time of war or national crisis than at any other. Their role is vitally important to voters’ understanding of what their leaders propose to do in their name. The world since September 11 2001 seems to have seen a growing effort in time and money from governments keener than ever to get their side of the story across. The controls placed on reporting in Iraq – for example, “embedding” journalists with troops – during the 2003 invasion and beyond were a reflection of this. The idea that “TV lost the Vietnam war” – wrongheaded though it may be – retains an enduring power.

Russia’s massive deployment of media resources to mobilise supportive opinion of its policies in Ukraine and Syria is just one example. In that case, many Russian journalists have appeared willing to support their country’s foreign policy. Given the overwhelmingly patriotic tone of contemporary Russian coverage of international affairs, that may be the only option for anyone wanting airtime.

Yet what of other cases? How well are audiences served by a one-sided view of events? The answer is not at all well, as The New York Times acknowledged when admitting that coverage of the run-up to the Iraq war “was not as rigorous as it should have been”. The New York Times was not the only guilty party. At least they decided to admit their failings.

Journalism has risen to unprecedented challenges with varying success. Some of The New York Times’s reporting of the occupation of Iraq and the insurgency which followed was truly outstanding. Yet western journalists covering the “War on Terror” in its various forms have found themselves tested.

Centre of conflict

The attacks on Brussels on March 22 were a reminder of why this is. Journalists find themselves at the centre of events as never before. The bombers struck at soft targets to inspire fear. That fear spread as the coverage continued. Without the coverage – or at least if there had been less of it – would the attackers’ aim have been frustrated? Perhaps so. But even if the authorities had requested that, it would have been wrong to agree.

As Greste noted, journalists find themselves at the centre of conflict as never before. Not just war, but political battles, and “anti-terrorist operations”. They are targets. Islamic State beheads them. Others seek to co-opt them.

Ethical dilemmas emerge. In July 2005, I was among the BBC editors who agreed to a reporting blackout as police closed in on the suspects in a series of failed suicide bombings. The idea was that live TV coverage might have tipped off the wanted men. Was it right to do the authorities’ bidding?

There are more questions. How seriously should editors take warnings from anonymous “security sources” about threats? Is this important public safety information, or spin aimed at securing extra funding?

What about stories affecting journalists themselves? As a correspondent based in Brussels, I passed through Zaventem airport countless times. How to keep out of reports the thought “that could have been me”?

The rise of Islamic state, just as much as Tuesday’s attacks, show the value of good journalism. The former by its initial absence from the news – hence the surprise which accompanied the group’s territorial gains in Iraq and Syria – the latter by telling people about the world they live in. Few did, or could, report the rise of Islamic State. Its seizure of territory, and oil fields, came as a shock.

Ideally, journalists would do their jobs without having to take sides – although some would still choose to do so, as we saw by the shabby attempts by controversialist Brexiteer columnists to make a political point out of the Brussels bombs.

In a world where, despite its complexity, journalists are under pressure to be with us or against us, their craft cannot function properly – and that is a loss for all of us.