In a recent speech celebrating 30 years of the Victorian AIDS Council, Adam Carr, one of its founders who went onto pursue a PhD in history, made the point that:

…not many people get to make history in their youth, and then to come back 30 years later and pass judgement on their own actions.

Indeed, some academic historians might say it is a privilege too fraught to indulge.

But many contemporary academics have come to understand that the personal can be scholarly: that we not only have little to fear in foregrounding our own experience but that we have much to gain. If Carol Hanisch’s much-quoted dictum that “the personal is political” is true, there is great value in a scholarship which is both personal and political.

Few Australian academics embody these characteristics better than Dennis Altman. His latest book, The End of the Homosexual?, is a great example of what might be called personal scholarship or conversational history. He gives a impressive overview of the evolution of the LGBTI rights movement from its radical beginnings in gay liberation through to the current fight for same-sex marriage. At each point, it seems Altman was there, marching, helping out, giving a speech, having a chat or observing in the corner.

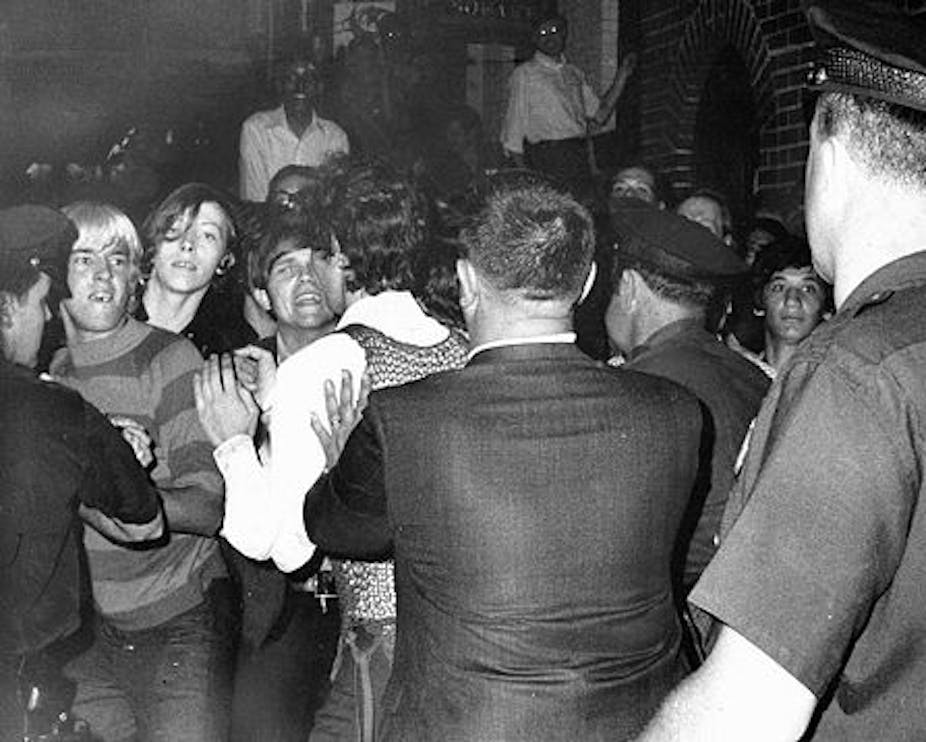

He relates how he became a gay activist “by accident largely as a result of living in New York in 1971, when the gay liberation movement was starting”. He found himself at the heart of that movement by sharing an apartment that became the meeting place for an early gay movement publication: Come Out.

In 1971, Altman wrote one of the first books about the then nascent gay liberation movement, Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. It is sometimes referred to as The Female Eunuch of the gay movement and like Germaine Greer’s classic, it has had a lasting impact on our understanding of the evolving politics of sexuality.

Over the last 40 years, Altman - until recently professor of politics at La Trobe University (he is now a professorial fellow) - has been a prolific author, publishing a novel, a memoir and a range of other books on homosexuality, AIDS and the politics of social change. He has been an indispensable part of the LGBTI rights movement both in Australia and globally and has played a significant role in HIV/AIDS politics nationally and throughout the region as the president of the AIDS Society of Asia Pacific.

Altman’s new book takes its title from the final chapter of his 1971 classic in which he posited the birth of a future “new human”, so comfortable with fluid understandings of sex, sexuality and gender that rigid binaries such as gay and straight would no longer be necessary or helpful.

In 1971 Altman began that chapter: “any movement has a double impact both on those it represents and on society at large”. He goes on to write:

Homosexuals can win acceptance as distinct from tolerance only by a transformation of society, one that is based on a “new human” one who is able to accept the multifaceted and varied nature of his or her sexual identity. That such a society can be found is the gamble upon which gay and women’s liberation are based; like all radical movements they hold to an optimistic view of human nature, above all to its mutability.

These two themes: the intersection of the movement for LGBTI rights and the broader politics of social change, and the link between the personal and the political at the heart of this, became central to Altman’s writing, scholarship and activism.

In The End of the Homosexual?, Altman returns to these questions. In charting the journey of LGBTI people through tolerance to acceptance, he catalogues the impressive gains that now see homosexuality as an unquestioned part of mainstream life in many parts of the world.

But what are we to make of a world which has a pro-marriage equality US president but an increasingly homophobic Russian leader; a world where legal impediments to homosexual behaviour have been removed in most of the western world but where lesbian and gay young people still account for a larger portion of suicide risks than their peers? As Altman asks: “is the glass half empty or half full?”

Altman manages to maintain some of the optimistic utopian fervour clearly apparent in his original book, but he is scrupulous in documenting the many stress points, contradictions and outright oppression that still exists in some parts of the world and in many discrete corners of otherwise liberal spaces.

Strangely, it is not the “end” part of the proposition of the “end of the homosexual” that has proved most problematic. It is the notion that there is such a being as “the homosexual” – singular. One of the most interesting aspects of Altman’s book is the way that he moves at a rapid pace across geographic, historic, gender and other boundaries in charting the birth of these many homosexualities.

One of the other significant observations Altman makes in concluding this new book is about that intersection between society and social movements - that “double impact” that he noted in 1971. Unlike the changes in gender politics, the changes in our attitudes to homosexuality remain “largely invisible” in the larger story of social change in Australia. Altman notes how recent books by George Megalogenis, Gideon Haigh and Jeff Sparrow have each documented the progress of social change in interesting ways but:

…remain too heteronormative to notice the extent to which the perception, regulation and popular imagination of homosexuality has changed over the past few decades.

The End of the Homosexual? begins to correct that omission. However, it points to the need for more work that brings the LGBTI story into the larger story of the nation and of social change.