We’re about 10 years into the much-rumoured development of a film adaptation of Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy’s most famous novel. The track record of the project has been terrible.

Its writers and producers seem stuck at the script stage. But that’s for a good reason. Blood Meridian is probably unfilmable. It’s not because of its vistas of gruesome violence, its historical tale of U.S. imperialism in the mid-19th century Southwest, or its narrative lyricism untranslatable to film. Rather, it’s because the novel’s religious vision is terrifying, and the casting required to capture it probably impossible.

Blood Meridian tells the story of a nameless protagonist known only as “the kid.” The kid joins John Joel Glanton’s real-life gang of American mercenaries circa 1849-50. Although hired by the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua to combat the Apaches and Comanches with whom they struggled over territory, the notorious gang soon began killing and collecting “receipts” — that is, scalps — from other, peaceful, Indigenous peoples, and then from the very Mexican citizens they were hired to protect.

There have been plenty of violent films depicting historical fiction, including ones made from McCarthy’s other work like No Country for Old Men, so it is not impossible to imagine a film adaptation of this critically acclaimed novel following suit. But what makes the film unlikely is the dark religious vision attached to the novel’s gruesome excesses. That vision centres around “judge Holden,” a terrifying character also based in the historical record.

The judge is a massive, hairless, albino man who excels in shooting, languages, horsemanship, dancing, music, drawing, diplomacy, science and anything else he seems to put his mind to. He is also the chief proponent and philosopher of the Glanton gang’s lawless warfare.

Previous plans proposed casting Vincent D'Onofrio in the role of the judge, and he may plausibly have the required size and otherworldly weirdness. Still, it might be impossible to capture the character’s quality of almost supernatural evil and strangeness as depicted in the novel.

The judge has been likened by some critics to a kind of Satan figure, who in one memorable scene brings Glanton’s gang the gift of gunpowder — reminiscent of the Satan in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, who likewise invents gunpowder during the angels’ rebellion from heaven.

But unlike Satan, the judge is no rebel; he seems, rather, to be highly attuned to the violent, material world around him. He’s not an antagonist of creation, but rather an enthusiast of the violent wickedness he finds already there. This has led several influential critics to interpret the judge not so much as a devilish opponent, but as a kind of sub-deity in the unusual second-century Common Era body of religious ideas known as Gnosticism.

Gnostic thought: The judge as an evil god’s deputy

In some sense, the Gnostic thought that briefly flourished in the ancient Mediterranean world turned Judeo-Christian theology upside down, questioning the goodness of the traditional Jewish god. It would come to be seen as a heresy by what eventually became orthodox Christian theology.

To get a sense of the true strangeness of Gnosticism, it’s best to think of it as having evolved out of failed Jewish and Christian apocalypticism.

This apocalypticism’s modern incarnation is the premillennial dispensationalism animating white American evangelicals today — the expectation that we’re living in the End Times, with God soon to return in judgement.

In the apocalyptic worldview, God had a cosmic enemy, Satan, who had been given lordship over the world temporarily. Apocalyptic Jews and Christians imagined their suffering and pain not as punishment from God, but as the consequence of this temporary dominion on Earth of Satan and his worldly servants.

But God would soon send a divine judge and conqueror to sweep away these powers in a cosmic battle that would institute a heavenly kingdom on Earth. Early Christians believed this divine conqueror would be a returned Jesus.

But Jesus didn’t come soon. Faced with the collapse of these apocalyptic expectations, some early Christians adapted their views. In this theological innovation, the suffering of God’s people — now Christians rather than Jews — wasn’t caused by the temporary rule of God’s cosmic enemy and his earthly vassals. Rather, the creator-god himself, Yahweh, was causing human suffering, or was ignorant or uncaring about it.

In some Gnostic cosmology, humans contained a divine spark from an immaterial, good, spiritual plane full of divine beings. Those sparks had been captured and put into base material bodies by this “evil” creator-god Yahweh.

Yahweh, either deceptive or ignorant, claimed to be the only god. He kept us in ignorance of our divine, spiritual origins, but the higher spiritual plane sent messengers to alert us to our true natures. Gnostic Christians believed Jesus to be such a messenger. Meanwhile, this Yahweh, newly reconceptualized as evil, employed deputies to ensure his rule and our continued ignorance.

One such deputy has been interpreted as Blood Meridian‘s judge. He motivates the Glanton gang toward war. He tells parables that ensure their ignorance. He seems highly sympathetic to the material world and the violence he finds therein, “as if,” the novel puts it, “his counsel had been sought at its creation.” How could one cast this charismatic, evil sub-deity in a film version?

To early Gnostic Christians — and maybe to readers of Blood Meridian today — this scheme seemed to be a reasonable answer to why a good god didn’t intervene to stop human suffering, the predation of human on human violence. As the judge asks of this hypothetical good god, “If God meant to interfere in the degeneracy of mankind, would he not have done so by now?”

Violence, suffering and evolution

Even if we don’t buy this loopy theology when reading Blood Meridian, we have to somehow account for the sympathy the judge seems to have for the violence and suffering in the world. Perhaps this is why McCarthy portrays the judge as a kind of evolutionary scientist.

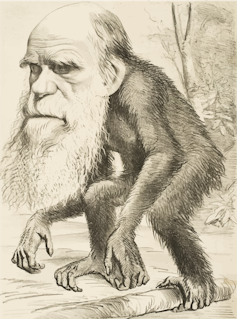

The novel takes place around the mid-19th century, a time when advances in geology and biology were leading Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace to articulate their theory of evolution through random mutation and natural selection.

These ideas were in the air at the time, and McCarthy strangely portrays the judge as on the cutting edge of science. He collects and sketches dinosaur fossils. He sees in the geological record eons of past time, calling the rocks he finds the “words of God.”

He’s also an ornithologist, reminiscent of Darwin in the Galapagos, collecting finches. He gives lectures on the age of the Earth and the fossils of extinct species to the assembled gang, which the novel often refers to as “apes,” recalling the popular caricature of evolution.

And it’s likely that McCarthy had evolution on his mind when he was writing Blood Meridian in the early 1980s. A prohibition against teaching evolution had been struck down by the Supreme Court in 1968. In response, Christian fundamentalists had proposed a new, “scientific” version of Biblical creation that could be taught alongside evolution, as an alternative. Legal challenges to this new “creation science” were making their way through the courts across many Southern states while McCarthy was writing his novel.

Opponents — and eventually the Supreme Court — contended that this was mere religion dressed up as scientific method. Like another novel published in 1985, Carl Sagan’s Contact, McCarthy’s Blood Meridian seemed to be closely attentive to the evolution versus creation science debate that was the context for its composition. And like other American writers, McCarthy was watching the unexpected return of the nascent Christian Right to political power and social prominence.

God’s dark design

Blood Meridian seems to share creation scientists’ dark views about evolution: That there’s no way a good God would choose the suffering entailed in natural selection to generate the diversity of our planet’s species. Natural selection is an intensely amoral process. But it’s absolutely immoral if it was chosen by God.

In natural selection, it’s not the organisms that try hard that get to successfully pass on their genes. Rather, the dice are cast before organisms are born, and a huge amount of luck is involved in whether organisms reproduce, or fall to predation or starvation. These forces of selection pressure are not the unfortunate side effect of progress. They are the critical engine for increased complexity and adaptability.

Any God who chooses this method really doesn’t care about animal and human suffering. Apprehending this theological problem, Christian fundamentalists use it to try to persuade mainline and liberal Christians out of their belief in evolution. Perhaps this is why the judge, ultimately, seems to be both a philosopher and enthusiast for what Darwin would call in On the Origin of Species the “war of nature” that he discovers. The judge is sympathetic to the violence inherent in this creation.

Whether the judge is a deputy serving an “evil Yahweh” or a scientist discovering God’s dark designs in nature may not ultimately matter. Blood Meridian is an intensely religious novel that articulates our worst fears — about the world, about each other, about God Himself. Perhaps it’s best to let this novel lie sleeping. Let’s not awake its power for film audiences at all.