Author’s update, January 29: In the week since this article was published (on January 23), Labor has moved to address the funding “black hole” in its plans to reduce Queensland’s debt, mainly by adopting very modest election promises. However, the LNP has not addressed its larger financial “black hole”, yet.

Since voters should know what the parties presented in their economic plans, this article remains as originally published apart from updates to the introduction and an explanatory note in the Labor section. The headline on this article has also been updated, from ‘The black holes in LNP and Labor plans to fix Queensland’s debt’ to ‘Uncovering the black holes in plans to fix Queensland’s debt’. My final conclusions of serious flaws in the plans from both parties to address Queensland’s financial situation still stand.

At the January 31 state election, Queenslanders are being asked to vote on the future of multi-billion-dollar state assets.

But I’m sorry to say – having examined the Liberal National’s Strong Choices plan, state budget papers, Queensland Treasury Corporation annual reports and Labor’s “debt action plan” – that as of the time of first publishing this article (January 23), both major parties had unexplained black holes in their economic plans. While Labor has since moved to address the black hole I identified here, the LNP has not rectified their serious mistake.

So, the central argument remains. Both major parties lack a clear, well-explained strategy to tackle the state’s debt.

A growing debt problem

I’ve long argued that Queensland has a debt problem. Before the last Queensland election, I warned that fast-growing state debt was casting a shadow over the Sunshine State’s economic future, which neither major party seemed willing to talk about at the time.

So three years later, it’s been heartening to see debt and the economy rate as key issues for many voters in the 2015 campaign.

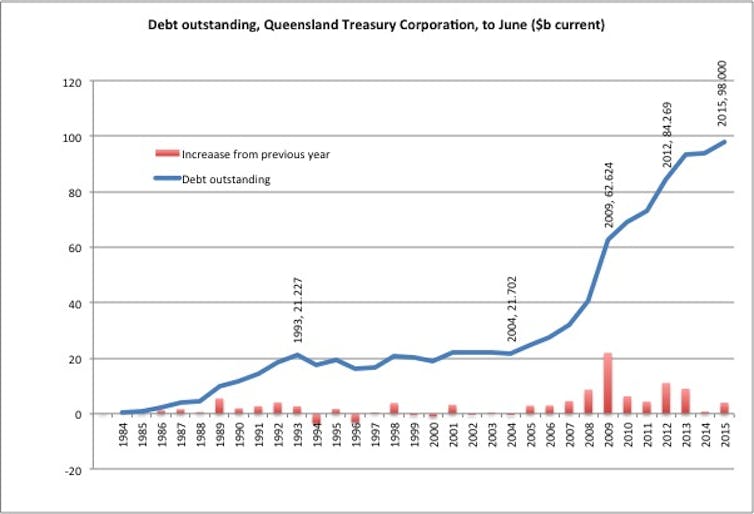

As the graph below shows, debt is on track to be A$14 billion bigger by June 2015 than at June 2012. Operating, interest and capital purchases costs were not fully covered, despite around A$10 billion in rail and motorway privatisation receipts during the period. This is an annual average shortfall of A$4.67 billion.

This compares with a A$22 billion rise in debt in the three preceding years under Labor, despite a further A$10 billion in privatisation receipts. That averages out to an annual shortfall of A$7.33 billion.

Both are stunningly bad results. Despite assets being sold, debt continued to rise under both governments. Queensland’s suspicion of asset sales seems well founded.

The Global Financial Crisis and responses to natural disasters such as the 2011 Queensland floods and earlier south-east Queensland drought explain a part of the problem, particularly under Labor. But both governments clearly failed to manage their budgets.

Interest on existing general government debt (now A$42 billion) is not being serviced (see the notes to the graph). This critical problem remains inadequately addressed in election proposals from both major parties.

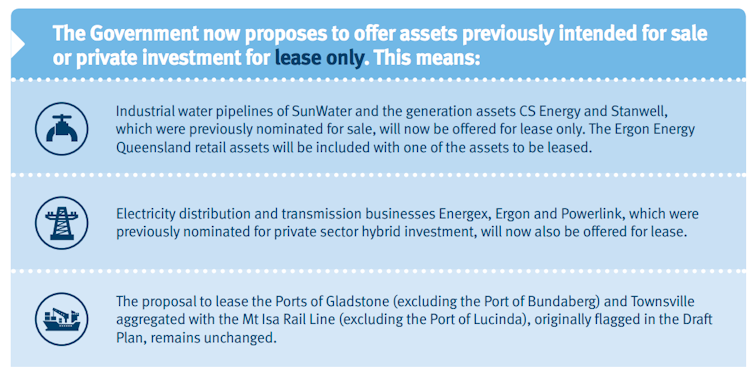

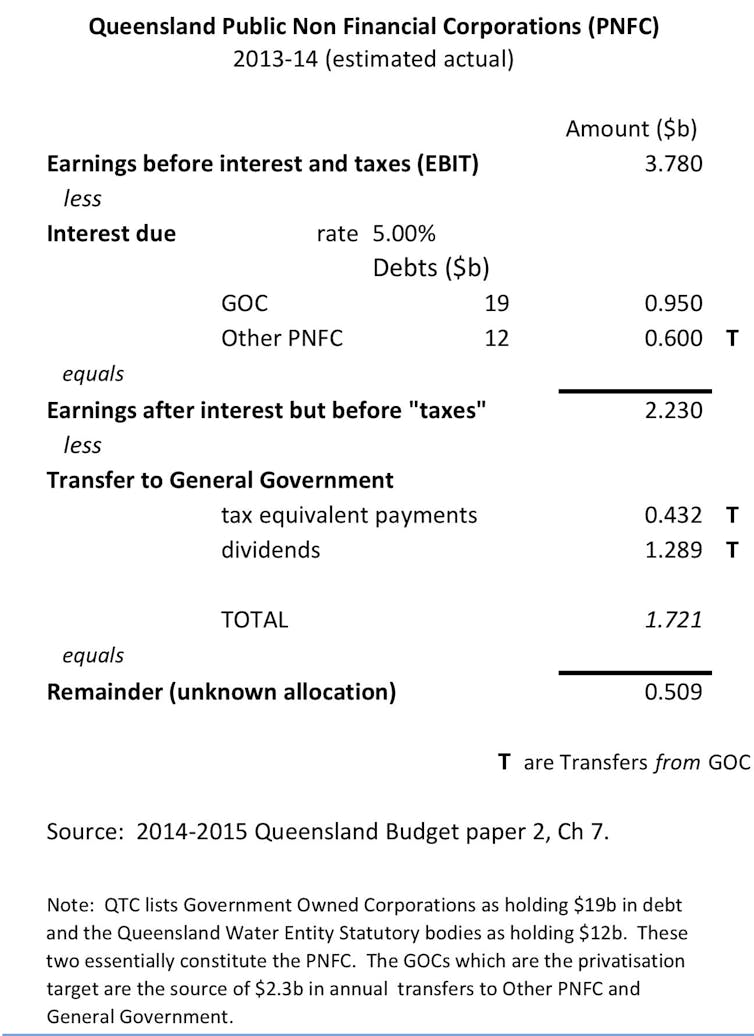

The assets now up for lease (listed below) are principally the major electricity and transport assets held by government-owned corporations (GOCs). This group has been performing well, fully covering interest on their own A$19 billion debt while also covering interest on the A$12 billion debt of Water Statutory Authorities holding the little used South-East Queensland water grid assets, such as the Gold Coast desalination plant. This does not include Sunwater which is to be leased.

Additionally, each year the government-owned corporations provide around A$1.7 billion to general government revenues, which was 3.8% of 2013-14 revenue. The balance sheet below shows the details.

So how do the parties propose to address Queensland’s debt? The Liberal National Party plans to “lease” profitable government-owned corporations. In contrast, Labor wants to build up GOCs for even greater returns to the public.

The LNP’s plan: long-term “leases” but at a long-term cost

Responding to public consultation that found asset sales remained unpopular with Queenslanders, last year the LNP amended its privatisation plans. Instead of outright sales, it is now talking up the value of long-term leases.

A lease usually involves regular payments each year for the life of a reviewable lease. Yet with the LNP plan, all the money is to be received upfront, not annually, and no reviews are detailed.

Assumptions used in calculations will be critical – and I expect they would favour the buyer. Sellers rarely have the upper hand.

Under the LNP plan, the cash hits now (within five years). With 99-year “leases”, assets apparently provide over 90 years of no returns to Queenslanders, exacerbating both future budget and income issues.

That means more than 90 years of not receiving the current (and likely rising) A$1.7 billion annual income from government-owned corporations, and interest cross-subsidies. Naively, that’s more than A$150 billion gone in the long-term for perhaps a historically high A$37 billion today.

Assuming an LNP government gets the prices it want for asset leases, the LNP has forecast the annual interest saving (at 5% per year) from asset sales would be A$1.25 billion. That’s half-a-billion dollars less than the current A$1.7 billion coming into government coffers from the government-owned corporations.

To compensate for that loss, the LNP would need to generate net returns of A$0.48 billion each year from its A$8.6 billion capital spending fund. No evidence has been provided showing how that will happen.

Also, assets are returned at the end of a lease. Experience elsewhere is that they will be run down. We also don’t know any (early or final) termination costs.

We have had no clear answers from the government about what would happen at the end of the leases. That would be a problem for future governments.

Could the LNP economic plan be then “strong but wrong”? From my examination of the asset leasing proposals, I found a number of serious problems, with not enough detailed explanation to do more than this preliminary assessment of its merits and drawbacks. Even if they do manage to get A$37 billion for the leases, that price comes at a much bigger long-term cost.

Labor’s plan: no asset sales, and a hole that had be filled

Author’s update, January 29: Since this article was published on January 23 Labor has recognised and rectified the A$1.7 billion problem discussed in this section. Announced spending commitments are very modest, indicating a potentially worthwhile attempt to rectify the General Government problem explained below. However, given the black hole was there in the first place, it is worth understanding what the original gap in Labor’s debt action plan was.

Labor’s “debt action plan” was finally released midway through the election campaign. Outlined over just 12 pages, it involves retaining assets, restructuring organisations to improve efficiencies and using a (hopefully) increased income stream from government-owned corporations to pay down debt slowly. We might call this a “grow the GOC business returns model”.

The biggest criticism of Labor’s plan has been that it has a “A$1.3 billion black hole” and that there is an element of “fingers crossed” in relying on increased future revenue.

Is there any substance to those claims? From my reading of Labor’s plan, yes.

As I explained above, the government-owned corporation income stream is already committed to subsidise electricity prices across the state. So Labor is relying upon future improvements in GOC performances, rather than money that is currently free to spend. Restructuring may deliver some gains, large or small, but how much and when is unknown.

The 2013-14 state budget papers indicate that performance improvements do appear feasible, but there are clear short-term challenges. Some of these are in the regulatory environment, while others are in the market and wider economy. Commercial risks are both negative and positive.

Labor’s “enhanced” government-owned corporations might contribute while maintaining existing distributions. But this plan needs to achieve above the current A$1.7 billion in GOC returns – and any improvements that can be made may be slow.

Still, it is a positive that a Labor government would retain the government-owned corporations and have better prospects of growing public revenues than the LNP’s leasing plan.

Roads, rail and infrastructure

One issue Labor is yet to address in its economic plan is new capital spending.

Without the money raised from selling or leases state assets, Labor can’t come close to matching the LNP’s multi-billion-dollar promises in this election campaign to build and upgrade roads and rail lines across the state.

As of January 22, the LNP’s promised spending amounted to about A$5.3 billion compared to Labor’s A$1.3 billion. But there’s far more to come from the LNP, which has earmarked a total of A$8.6 billion for its capital spending fund.

If elected on its current platform, Labor would need to defer capital spending, or find funds elsewhere.

That’s not impossible. Little of the spending is urgent economically. A simple federal rule change (which is cost-neutral to the Commonwealth) would markedly narrow the gap between the parties on capital spending possibilities. If the federal government amended its temporary A$5 billion “asset recycling incentive” fund to alternately allow a temporary change in the National Highways arrangement from an 80:20 split to a 92% Commonwealth contribution, that would do the job (although not for spending on arterial and local roads).

However, the trouble for Labor is that the Abbott government set up the asset recycling fund – and it’s hard to see the Coalition choosing to make life easier for a Labor state government, or vice versa.

An unenviable choice on January 31

Having read the LNP and Labor economic plans, I’d like to be able to say that one or both parties have a clear plan to tackle the state’s debt – but they don’t.

Too many questions remain about crucial details of both major parties’ plans. Queenslanders are being asked to vote on faith or ideology, not the full facts.

Queensland’s debt problems are systemic, and it will take more than a debate over asset sales to fix. Nor will austerity or GST hikes help.

There are more promising approaches for an incoming government wanting to address Queensland’s worsening financial position – including refinancing to address high interest rates – which I hope to discuss in a future article.

The political choice Queenslanders face this election is whether to live off past capital for one final term, or to rework remaining capital for gain. Years of privatisation will stop this election (with Labor), or the next (as the LNP would have disposed of the last major saleable commercial assets). It’s now up to Queenslanders to decide when.

Read more of The Conversation’s Queensland election 2015 coverage.