This article is part of a series on how law enforcement is fighting crime across digital borders. You can read the rest here.

More than one decade ago, the United States government predicted that “technology will soon exist, if it does not already, to make depictions of virtual children look real”.

There is now evidence to suggest we have reached that point.

We need to consider the implications this may have for law enforcement agencies in combating child abuse material.

Read more: Child sex dolls and robots: exploring the legal challenges

When fears over child abuse material reached fever pitch in the 1970s, the internet was still in its infancy.

Since then, digital technology has advanced significantly. Lawmakers throughout the world, including Australia, have sought to extend laws prohibiting child abuse material to include pictures and videos created even without a child.

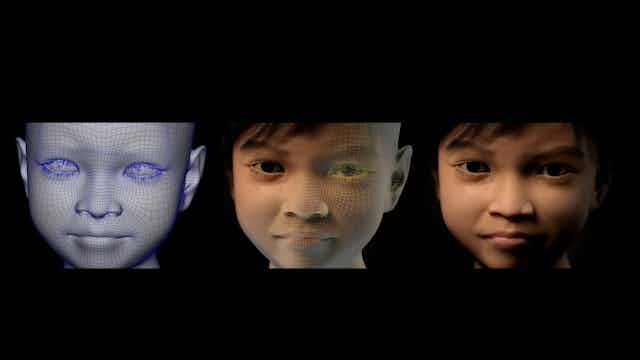

Sexually explicit images that are wholly computer generated, but that appear realistic, are known as “virtual child pornography” (VCP).

Although it is safe to assume cartoon depictions of children (say, Bart Simpson) would not be mistaken, distinguishing a photograph depicting a real child from VCP can be complex.

Virtual child pornography becomes too real

According to Hany Farid, a professor of computer science at Dartmouth:

[a]s computer-generated images quickly become more realistic, it becomes increasingly difficult for untrained human observers to make this distinction between the virtual and the real.

This is supported by a 2016 study conducted by Farid and his colleagues that showed approximately 250 participants 60 images of human faces. Half of these images were computer-generated, the other half were real.

The participants were able to correctly identify which images were photographic 92% of the time, but were only able to accurately classify a computer-generated image 60% of the time.

The second part of the study found that training increased the ability of participants to identify when an image was virtual.

These findings, along with advances in photo-imaging software, indicate the need for the courts to reconsider its belief that “juries are still capable of distinguishing between real and virtual images”.

Unlike laypersons, law enforcement officers are likely to have the training and skill to distinguish real images from virtual images of children. But there are reports suggesting that sometimes even “experts cannot know whether a digital image is real or virtual”.

Law enforcement using VCP to detect offenders

Nevertheless, VCP that is virtually indistinguishable from images of children creates new possibilities for law enforcement officers in catching criminals.

A sting operation conducted in 2013 used a fictitious virtual child character, “Sweetie”.

Created by activist group Terre de Hommes in the Netherlands as part of a sting operation aimed at tackling the growing threat of webcam child sex tourism, the apparently 10 year old Filipina girl reportedly misled thousands of men around the world (including in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom). These men were exposed after paying to see Sweetie perform sexual acts in front of a webcam.

While there is no data highlighting how frequently law enforcement in Australia use VCP, there are multiple reports of police using technology to catch online sexual predators.

In May 2016, for example, it was reported that three men in New South Wales were arrested after making “sexually explicit comments” to police officers pretending to be underage girls online.

Now that it is possible to create photorealistic images of children, perhaps Australian police forces will conduct their own Sweetie-like operations to target offenders.

The legal and ethical risks of VCP

While VCP may equip law enforcement agencies with a powerful weapon to detect and apprehend offenders, such police operations are fraught with legal and ethical concerns.

These operations may contravene domestic laws prohibiting VCP. They may also contravene laws in some jurisdictions, such as the United States, making it a crime to advertise VCP as material depicting real children.

There are no reported Australian cases dealing with the legality of police using VCP to catch predators. But the case law that involves police adopting fictional identities highlights the tendency of the courts to reject arguments challenging the lawfulness of such police stings.

For instance, the New South Wales case of R v Fuller involved a priest who used the internet to engage in sexually explicit communications with a 13-year-old girl. The “child” was really a fictitious person created by police.

The Court stated that although “the presence of an actual victim may aggravate the offence, the absence of a victim will not mitigate it”.

Read more: From live streaming to TOR: new technologies are worsening online child exploitation

In Australia, it is a defence for law enforcement officers to deal with child abuse material if it is for a “public benefit”. Given the societal interest in protecting children, the use of VCP to detect potential predators may be seen as acceptable.

Certainly, it is a public priority to catch offenders before they harm actual children. But just how far should the police be allowed to go to catch child predators? Do the ends justify the means?

An informed public debate on the potential use and misuse of VCP is needed.

Read other stories in this series: