Is it possible to opine about “the state of democracy in Asia”? Although some studies credibly do so, such a task seems challenging to say the least. This is due to the region’s proverbial diversity. And perhaps more so because of the slippery conceptual slope this question treads on.

After all, is democracy about inputs or outputs? Rights or governance? Representation or participation?

Elections are often seen as a more manageable component of democracy – a necessary but not sufficient condition. If they work well, elections serve to aggregate the will of an informed citizenry, hold power bearers accountable and evaluate their performance in office. If seriously flawed, elections can cement autocratic rule, lead to conflict and violence, and degenerate into mere charades or ritualistic performances.

Asia’s experience with elections has been mixed. Some countries have held competitive and inclusive polls since the 1950s. Other nations have only recently emerged from prolonged autocratic rule. Yet others restrict elections to the local level or limit the choice to one party.

The Electoral Integrity Project – an independent research effort based at the University of Sydney and Harvard University – recently released new evidence comparing the integrity of elections worldwide. The project’s annual report, The Year in Elections, 2013, evaluates 73 national parliamentary and presidential elections held in 66 countries from July 1, 2012, to December 31, 2013.

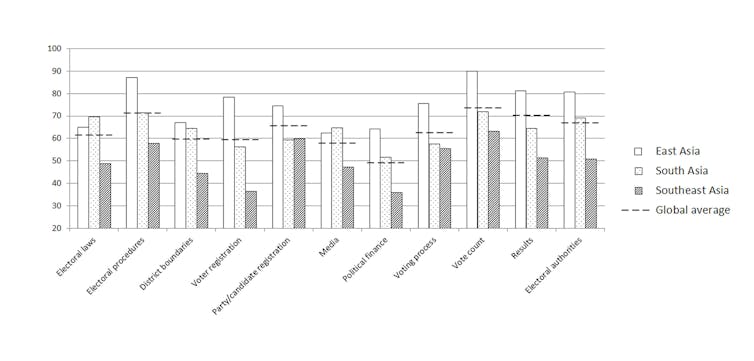

Data are derived from a global survey of 855 election experts. Immediately after each contest, domestic and international experts assess the election’s quality based on 49 indicators across 11 sub-dimensions of electoral integrity. These add up to a 100-point expert Perception of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index – with 1 being the worst and 100 being the best possible score.

How do Asian elections compare?

In comparison to other regions, Asia as a whole ranked rather poorly on the overall PEI index, with an average rating of 62.3. Only African countries scored lower on average (53.56), while the Americas (65.9), Europe (71.9) and Oceania (73.4) attained higher average scores.

Yet there are huge differences within Asia. Looking only at three sub-regions, some trends emerge.

Elections in East Asia seem to have become well-established affairs. This is suggested by above-average ratings across the board. South Korea and Japan lift up this region. But Mongolia is evaluated positively as well, ranking 24th in global comparison – above the United States (26th).

This is not to say that elections in these countries were without controversy. Revelations about the manipulation of Twitter feeds in an attempt to sway public opinion in Korea are one example of persisting problems. But the exceptionally high scores on electoral procedures, voter registration or vote count show that East Asian elections have become rooted in reliable administrative capacities.

Southeast Asia on the other hand lags well behind the global average. Heavily criticised contests in Cambodia and Malaysia highlight the sub-regional pattern.

Entrenched ruling parties cling to power against increasingly successful opposition movements and parties. This is reflected by poor scores for voter registration (the case of Cambodia), voting district boundaries (exemplified by Malaysia), or the overall problematic regulation of political finance. These elements are well suited to tilt the political playing field and undermine the integrity of elections as mechanisms of accountability.

Yet since citizens are perhaps not as acquiescent as they used to be, election results were challenged. The flawed contests led to protests in all three surveyed South-East Asian cases. It must be noted that the Philippines scored better on all dimensions.

South Asian countries in the sample roughly align along the global average scores. Problems that are associated with election day itself (voting process, results) seem to prevail. The sub-dimensions on media and electoral laws score better on average than in East Asian nations.

Looking at the details, a worrisome trend in this region becomes apparent: the prevalence of violence. Pakistan, Nepal and the Maldives all had a higher-than-average incidence of voter intimidation.

The Maldives also scored exceptionally low on electoral authorities (54.8 as opposed to 68.1 in Pakistan, 73.7 in Nepal and 79.4 in Bhutan). This likely reflects an ongoing power struggle between the country’s Election Commission and its Supreme Court. The latter annulled the 2013 presidential elections and recently sentenced the entire Election Commission to jail terms.

The empirical data from 2012 and 2013 show that elections in Asia range from relatively routine and well-established administrative acts in some countries to new, contentious and hopeful displays of people empowerment in other contexts. None of the surveyed elections can be characterised as meaningless charades – although the integrity and competitiveness of the contests varied starkly.

With elections already held and partially derailed in Thailand and Bangladesh, and important contests in India and Indonesia under way, the integrity of elections will remain a crucial issue for Asia in 2014.

As popular dissent shows, citizens throughout Asia demand professionally conducted and credible elections. Without a doubt, systemic questions about responsive and effective democratic governance remain to be addressed. But the empowering potential of elections is not lost on people around the region.