Can we really separate a “nice” internet from a “bad” internet? That appears to be the thinking behind David Cameron’s statements foreshadowing the introduction of “porn filters” and search engine roadblocks. These policies muddle together a range of intersecting and complex social issues in order to offer a seemingly simple technical solution to the concerns of an ill-defined “moral majority”.

Presenting a solution like this actively prevents serious debate. Making statements about pornography as well as rape and child abuse on the same day also lends support to the media’s inevitable direct association of the issues. And yet pornography is itself an uncertain category that has not yet been sufficiently researched to back up any definitive claims of association or cause and effect.

Connoisseurs of popular internet memes will, however, point to “Rule 34” as clear evidence of how an initially humorous observation has so readily become reality. The Urban Dictionary provides a definition of Rule 34 that says: “If it exists, there is porn of it.”

Despite this potentially disturbing realisation, the proposal for filtering internet traffic appears to ignore text-based and “soft” porn. The first unfiltered category is the domain of a specific genre of fan fiction writers whose output precedes the popularising of the web, and the latter confirms the apparent existence of Family Guy’s stereotype of “high-class British porn”.

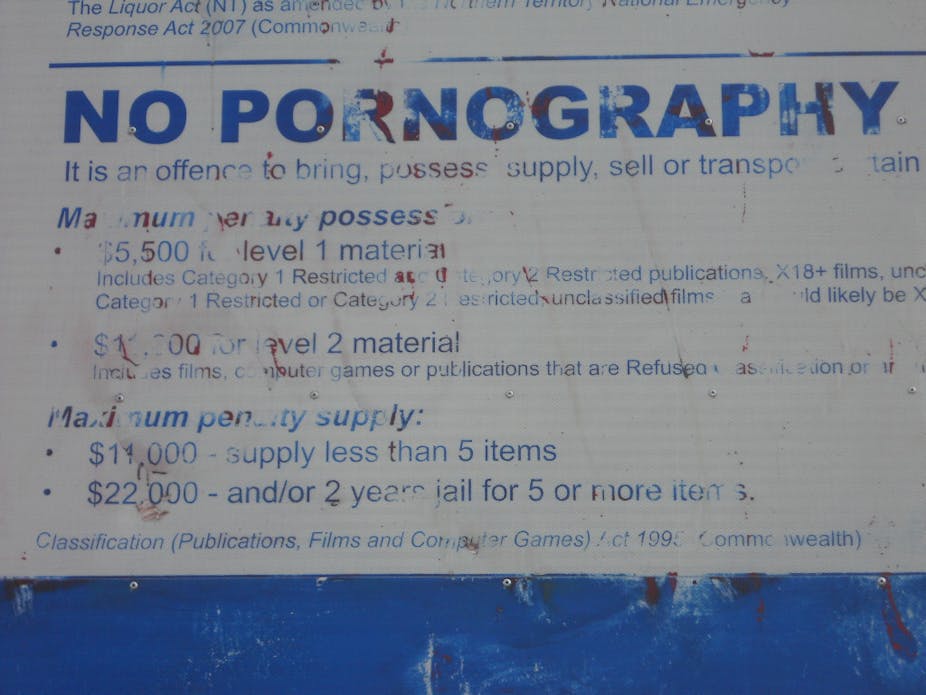

This prompts the question, what types of pornography are the internet service providers expected to block? And how will legal pornography that is to be blocked – we don’t yet know what this is – be distinguished from other apparently more acceptable forms that will not be blocked?

These questions introduce the technical side to the problem. Using technology to solve a social issue is a fraught tactic and in this case it ignores the resourcefulness of individuals and communities, both on and offline. The web makes the distribution of pornography easier and freer than any previous methods. Even a seemingly harmless site such as Tumblr is claimed to contain at least 10% pornographic materials.

Shared semi-private conventions also enable distributors and consumers of pornography to skirt filters and roadblocks. A classic example, though less effective these days, is the substitution of the “porn” keyword for “pr0n”. All the techniques of search engine optimisation embraced by multinationals and media outlets can be used by any audience who know the right keywords, and these keywords are themselves readily shared through social media. Blocking these most basic techniques will reduce the chance of accidentally stumbling upon pornography.

However underneath the web, amid the infrastructure of the internet, lies a much wider range of different methods for distribution and sharing that readily enables evasion of simple roadblocks or filters. These approaches do not necessarily use recognisably pornographic domain names, “jpg” file extensions or identifiable “flesh” tones. These methods can be easily identified in forms of sharing that have become conventional office technologies such as virtual private networks (VPNs), in anonymising technologies such as Tor and the peer-to-peer networking systems first popularised by Napster. All of these technologies are widely used for a variety of purposes that are not automatically illicit or illegal. Unfortunately, what can be used for pornography can also be used for child abuse and rape imagery.

Blocking internet access and predefined search terms may prevent the consumption of some materials. However, preventing our viewing of illegal, offensive or just distasteful material is the internet equivalent of gently closing the curtains and turning up volume on the radio. It is not a solution; worse, it may even encourage a naïve belief that child abuse and rape is somehow not a social issue.

Blocking some forms of distribution does not prevent the production of any of these materials or their consumption through different means. Technology has effectively made the production of digital images as easy as its distribution. The advent of “sexting”, the texting of sexually explicit images by teenagers, reflects the degree to which the combination of using a camera and texting with a mobile phone is a normal aspect of teenage life.

The readiness with which young people are prepared to send sexual images to boyfriends or girlfriends reflects the much wider issue of the sexualisation of teenagers and pre-teenagers. Where they are coerced into producing images by boyfriends or girlfriends for sexting it raises questions regarding the basis and “normality” of that relationship.

However, it is not necessarily the pornography that Cameron seeks to block that should be first examined for answers. A much wider and more serious self-examination is required of, for example, the career destinations of females held up as some sort of aspirational role models for young women or the relationship advice and guidance provided to young men by “lads mags”.

To resolve these problems we must look at society, not at technology, and at what promotes this dangerous behaviour rather than merely preventing people from looking at pictures of it.