Increasingly, our leaders talk of Australian values and presume that these arose organically, as though through some moral forge. An alternative view is that our national character and sense of identity have been shaped mostly by the land itself: we are a nation of individualistic, resilient and resourceful individuals because our land is isolated, expansive, capricious and unique.

Our country’s dust, drought, flood, blood and harsh beauty have made us what we are.

In a report published today, the Pew Charitable Trust compiled a series of perspectives on how people living in remote and rural Australia see their lives and country. We interviewed about 12 groups over the course of a year, trying to understand the intricate relationships between our people and our nature.

The core questions addressed in these accounts are simple. How do we see our land? How do we live in it? How do we care for it? How are we shaped by it? What do we value in it, or seek from it? And to what extent does the land now need us?

The responses were intriguing. For many Indigenous Australians, country is a defining feature, a place of belonging, imbued over countless generations with meaning and spiritual significance. For many other Australians living in remote regions, country still provides an embracing sense of place, a setting in which life can be meaningful.

“This place is where I feel safe and inspired and needed,” conservation manager Luke Bayley said of Charles Darwin Reserve. “I love the landscape – the big sky, the weathered rocks and the harshness; the beauty when it all comes together […] I also find it an endless journey.”

Although they may want different things from the land, miners, pastoralists, Aboriginal landowners, wildlife rangers and tourism operators all share some pivotal values, concerns and language.

All seek to treasure and maintain its productivity and health; all recognise the new threats that may be subverting it; all feel a sense of belonging and a responsibility to it; all appreciate the need to know how it works in order to draw benefit and sustenance from it; all see beauty and wonder in at least some of its constituent elements; all recognise the challenge of managing vast lands with few people; and, to some degree, all understand a mutual dependency between land and people.

This common ground provides a robust foundation for the collaboration and regional - or national - scale planning needed for the management of Outback Australia, with its unique challenges of complex environmental linkages across vast distances, pervasive threats and few management resources.

But the nuanced differences in perspectives are also important. Many living in Outback Australia identify strongly with other groups living on the land. But there is much scope – so far little developed – in remote Australia for increased recognition of the perspectives and expertise of others.

Most notably, there is extraordinary opportunity to bring together the intimate knowledge of country and its care held by Indigenous Australians with the often complementary strengths of land management based on western science. We can create distinctively Australian environmental management, based on intimate knowledge of country and the capacity to respond to its new threats.

Of course, there are also some notable inconsistencies among the perspectives we investigated, indicative of unresolved issues that need attention and a better process for conciliation or mutual understanding. For example, the values attributed to dingoes and wild dogs, and hence their management, remain highly polarised among people living in remote Australia. The elements of water and fire are pivotal in the Outback, and their use is often also contested.

Furthermore, just as our society has been moulded by our country, increasingly we are re-shaping the country, deliberately or inadvertently, expertly or ineptly. Across most of the world, biodiversity is in decline particularly in areas with high human population density and extensive habitat destruction.

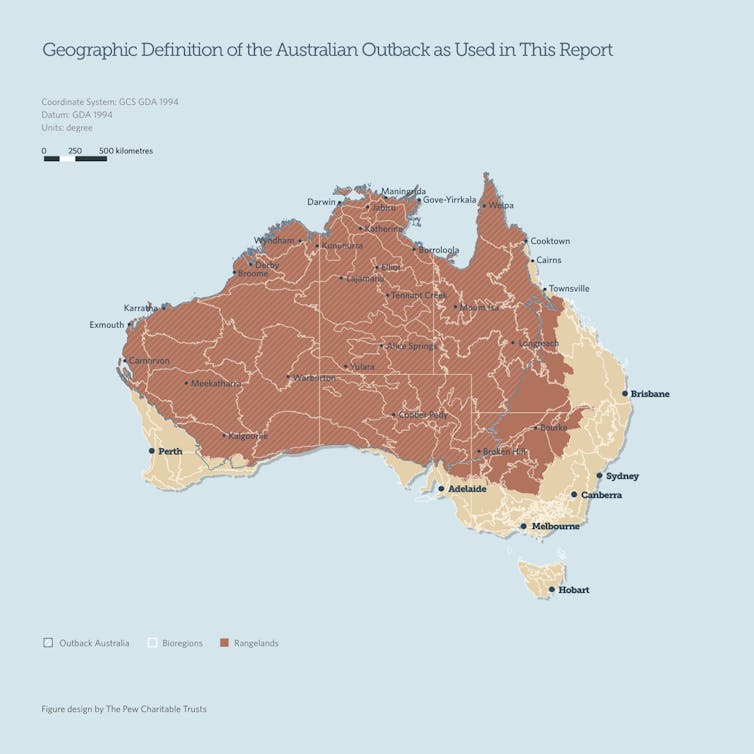

The Australian outback is one of the world’s few remaining large natural areas, along with places like the Amazon Basin and the Sahara. Such areas are most likely to long support functional and healthy ecological processes and biodiversity.

However, somewhat counterintuitively, in much of the Outback, nature is in decline even in its most remote and sparsely populated regions. This decline reflects the loss from many areas of a long-established, intricate and purposeful Indigenous land management, that has long moulded its nature. Now, fire is often managed inexpertly or not at all, leading to uncontrolled and destructive wildfire. And the decline of biodiversity and loss of productivity in remote Australia is due also to the extensive spread of many pests and weeds introduced over the last century or so, and the inadequate resources committed to their control.

Inexorably, we will lose much that is special in our nature unless we can collectively address these causal factors and manage our lands more effectively. The land managers we talked to are skilled and willing, but they need more support.

One example is Les Schultz, a Ngadju elder from the country around Norseman in south-western Australia. He told us he wants to see the Great Western Woodlands managed properly, saying,

We will always be around, and it ticks all the boxes of everything good in terms of outcomes for Ngadju people and the general community …. We need Ngadju rangers with boots on the ground.

A similar call comes from some pastoralists, such as Michael Clinch from the Murchison region of WA. He inherited a land long over-exploited by unsustainable levels of grazing, and is now seeking new management approaches to to take his land on “a journey of redemption”:

The Outback, to me, is the cathedral of Australia. We’re desperate to reclaim the quality and value of the Outback, and to achieve that vision we need support … We’re not asking for a handout, but by jeez we’re asking for a hand up. We need assistance to rebuild and restructure our grazing. If we don’t do it, who the hell will?

The accounts showcase people at home in their country. Such accounts, of characters living in the bush, have long been emblematic for our nation. But these lives represent a diminishing minority of Australians.

In our increasingly urbanised society, for much of our nation’s population, the bush remains quixotic and unfamiliar, to be experienced superficially or fearfully. One objective of this collation is to allow urban Australians to see and feel the country through the eyes and hearts of those who are immersed in it.

We would like all Australians to more appreciate the care bestowed on our land by those who cherish it, the benefits we all derive from that care, and the need to better support those who seek to maintain our natural legacy.

We cannot live well in this land unless we understand it, and value it.

This article is based on Outback Voices, a report compiled by the Pew Charitable Trusts.