The National Churches Trust has launched a campaign to save the UK’s historic churches. Backed by the actor Michael Palin, it highlights the need for a national approach to address what the trust has called the “single biggest heritage challenge” in Britain.

Entitled Every Church Counts, the plan covers six crucial points, including comprehensive professional support for the volunteers who keep places of worship open, dedicated public funding and more promotion for tourism to churches and chapels.

Church communities and other heritage organisations have lauded this push to highlight the significance of places of worship within British heritage.

From Saint Martin’s Canterbury, probably built during the Roman occupation of Britain sometime before 597, all the way to Liverpool’s grade II-listed Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King, designed by Edwin Lutyens and Frederick Gibberd, and completed in the 1960s, the UK’s urban and rural landscapes are inscribed with 1,500 years of ecclesiastic history. Without a comprehensive national plan to support places of worship, including those of non-Christian religions, my research shows that these physical repositories of British history and identity could be lost.

The state of the UK’s churches

In November, Historic England published its 2023 Heritage at Risk register. It lists 4,871 historic buildings and sites in England at risk from disrepair or inappropriate changes. Although this total represents an overall decrease from 2022, places of worship are noteworthy for being the only category with a net increase since the previous year. The register now counts 943 sites, an increase of 24 from 919 in 2022.

The situation in Wales and Scotland is similarly challenging. Cadw, the Welsh government’s historic environment service, reports that 10% of listed places of worship in Wales are vulnerable. Historic Environment Scotland, meanwhile, lists 195 religious buildings on the Scottish Buildings at Risk register.

Many churches are at risk of closure due to structural problems far beyond the capacity of local congregations to fix. Unlike some European countries, the UK government does not provide regular funding to churches for repairs. Even the national Christian denominations, such as the Church of England, the Methodist Church in Britain, and the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, are not able to keep up with the costs.

There are pots of money available through the National Lottery Heritage Fund and other grant schemes. However, these are highly competitive and the amounts they can offer do not always cover what is needed.

In 2013, the Catholic Archdiocese of Southwark received over £900,000 to restore the Shrine of St Augustine in Ramsgate, Kent. It was designed and built in the 1840s by architect Augustus Pugin, best known for designing the Elizabeth Tower in Westminster, home to Big Ben.

A second phase of repairs to the roof was undertaken in 2023 after a new public grant of £272,000, which also required St Augustine’s to raise a further £68,000 from other funding sources and donations.

Between 1995 and 2017, the National Lottery Heritage Fund granted £970 million to places of worship across the UK. It is currently distributing a further £1.9 million through the National Churches Trust. But this is not nearly enough. The Church of England alone needs £1 billion, over the next five years, just to cover essential repairs.

One of the proposals put forward by the new campaign is to encourage local authorities and public bodies such as the NHS to use places of worship for their activities and events. This could channel other sources of funding into repairing and upgrading church facilities, while also providing much needed community spaces in areas where many have closed due to funding cuts.

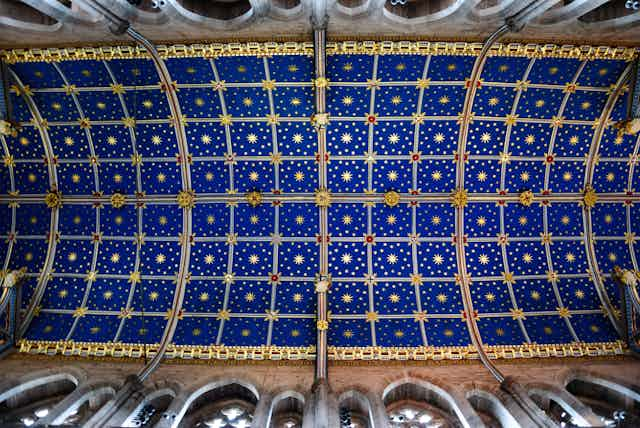

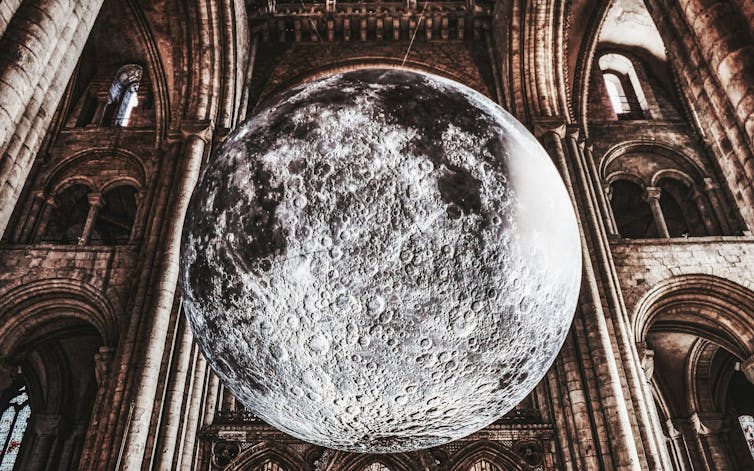

Anglican churches regularly open their doors to baby and toddler groups, food banks and even large exhibitions like Peterborough Cathedral’s display of Star Wars memorabilia or artist Luke Jerram’s Museum of the Moon travelling show, currently at Winchester Cathedral. Research has shown this can be a way to bring life back to under-used churches, particularly rural ones.

What is a church for?

However, expanding the use of a church can also be incompatible with the religious beliefs of the faith community to which it belongs. For such groups, the sacred nature of their places of worship must be maintained.

This raises the question of what roles churches play in today’s society, a question I have researched in collaboration with the Catholic Bishop’s Conference of England and Wales. Under Roman Catholic Canon Law, the entire church building is considered sacred due to the presence of the Blessed Sacrament within it. Activities hosted within churches (but not in auxiliary buildings, like halls) must be consistent with their holy nature.

Catholic churches sometimes struggle when applying for heritage support to meet expectations that their projects should be of value to wider society, which is usually assumed to have more non-religious priorities and needs.

However, everyone can benefit from such reserved places. They can support community mental health and wellbeing by providing quiet public spaces for reflection and tranquillity.

Catholic churches, in particular, are typically kept open throughout week days, for all visitors, religious and non-religious alike. In urban areas with high levels of deprivation, they can sometimes be the only such spaces.

Further, historic churches would not exist today without the continuing faith and practice of worshipping communities. Other countries recognise people’s rituals, beliefs and traditions as part of what Unesco defines as “intangible cultural heritage”. This refers to the practices, representations, knowledge and skills that provide people with a sense of continuity and cultural identity.

Social anthropologists rightfully question how the idea of intangible cultural heritage can actually oversimplify the complex realities of people’s experiences. It can also be used to promote commercialising and exploiting culture at the expense of local people.

However, research also shows that the tangible and intangible qualities of heritage are inherently inseparable. Recognising the value that practices like bellringing and choral singing, say, contribute to the belltowers and abbeys that host these aural traditions, will surely benefit their preservation.

The intangible cultural and religious elements of a place enhance the meaning and value of its built environment and material. Church buildings should be prized – and protected – for the vibrant living traditions of Britain’s diverse religious communities, as well as what they tell us about our past.