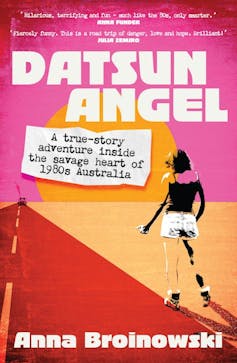

In the final pages of her memoir Datsun Angel, writer and filmmaker Anna Broinowski identifies the book as a “call-to-arms critique [of] the eighties patriarchy”. She questions whether women like herself – that is, the well-educated, sexually liberated beneficiaries of second-wave feminism – are really better off than their 1940s counterparts.

Given the many terrifying encounters her young headstrong protagonist endures at the hands of men as she seeks to make her independent way in the world, it is a question worth considering.

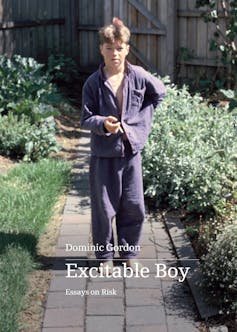

Review: Datsun Angel: A True Story Adventure Inside the Savage Heart of 1980s Australia – Anna Broinowski (Hachette) & Excitable Boy: Essays on Risk – Dominic Gordon (Upswell)

Broinowski – or “Bronco” as some wanky auteur from the Sydney University Dramatic Society labels her – is a first-year law student in search of her tribe. It definitely isn’t the “duckbill loafer” crowd, who sit around the lecture theatre trading professional lineages the way Bret Easton Ellis characters trade business cards. But it isn’t quite the avant-garde art crowd looking for anonymous vaginas to cast in their latest 16mm masterpieces either.

After a series of awkward attempts at finding her place on campus, and feeling thoroughly cynical about the surrounding city’s intrinsic phoniness, Broinowski embarks on an 8000-kilometre, month-long hitchhiking trip to Darwin and back with her good mate and partner in disillusionment, Peisley.

Reconstructed from the travel diary the author kept at the time, the adventure is everything you could possibly hope for in a road trip – provided you (or your daughter) aren’t the one taking it.

Datsun Angel proves the old adage about time and tragedy making for champagne comedy. Kidnapped by amphetamine-fuelled truck drivers intent on raping and then murdering her – or murdering and then raping her – Bronco is saved by a tinny-swilling entrepreneur, whose “crowning achievement was establishing dwarf-throwing as a pub sport in Queensland”. She is passed on to a Vietnam vet driving a stolen Commodore, who has to be roused from slumber with a broom handle because his first instinct upon waking is to strangle.

Structurally and generically, the book follows a well-trodden path. It self-consciously situates itself as a cross between the substance-induced exuberance of Jack Kerouac and Hunter S. Thompson, and the provincially impassioned politics of Australian novelist Xavier Herbert.

Tonally, I could not get comedian Julia Zemiro’s voice out of my head while reading (maybe because her name is on the front cover), but the critical thinking on issues of class, gender, race and sexuality owes a debt to the forefathers of the 1980s Arts degree: Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault and Umberto Eco.

I will perhaps be accused of reading something that wasn’t there (or even more egregiously, of projecting my own discomforts and biases), but beneath the explicit critique of the patriarchal power structures of Australia’s oldest university I sensed an implicit critique of the modern HR department that has since been erected over the top. For all her progressivism, there is a note of nostalgia ringing through Broinowski’s recollections. Datsun Angel harks back to a looser – dare I say, more enjoyable – university experience.

Written four decades after the fact, in a time when online consent modules are compulsory requirements at the institution where Broinowski once studied (and now lectures), the stories in this book offer a hedonistic counter-narrative to the one now used to swaddle newly enrolled students. The narrative promises, against well-intentioned assurances to the contrary, that what doesn’t kill you will, at the very least, make for a good story later on.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but the target reader for this book is a tertiary-educated, middle-class mother of two, whose young-adult children, currently enrolled in university, roll their eyes and scoff with embarrassment (and a touch of pity) every time Mum gets that wistful look in her eyes and says, You two wouldn’t know the half of what I used to get up to!

Broinowski goes part way towards acknowledging as much when she ends her postscript with: “If you’re male and reading this, kudos. I hoped you would. Please pass it on.” For what it’s worth: I am. And will!

In all seriousness, though, I suspect the real barrier to a more general readership will be one of class and, by extension, education rather than gender. Like many campus novels, you’re either in on the joke or you’re off doing something more productive with your time than reading books. Despite her best efforts (forcing esoteric Freudianisms into the mouth of the truck driver, whose idea of high culture amounts to Kevin Bloody Wilson playing his guitar north of the fifth fret), many of the academic references are likely to be lost on those who failed to obtain a distinction average.

There were a few anachronisms that caught my eye. I am pretty certain “giving zero fucks”, for example, was not something you could do prior to this millennium. And I failed to appreciate the mystical significance of the Datsun angel who visits his aura upon the book’s title and several of its chapters.

But these superficial reservations aside, Datsun Angel is a book that delivers on the promise to take its reader “inside the savage heart of 1980s Australia”, and one that never forgets its chief purpose along the way either – to entertain.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

Detachment

Excitable Boy: Essays on Risk is the debut collection from Melbourne reprobate turned serious writer, Dominic Gordon. 38-year-old Gordon may be living the life of a distinguished man of letters these days, but this is certainly not the case for the adolescent version of the author we encounter throughout the book.

Young Dominic spends his time cutting security tags off Ralph Lauren polo shirts, punching on with strangers at parties he wasn’t invited to in the first place, lighting train station bins on fire for the sheer fuckery of it, jerking off in public places, and vandalising private property while high on drugs purchased with money stolen from unattended cash registers.

For this delightful individual, who boasts of being so out of touch with civil society he doesn’t know who the Prime Minister of Australia is, the word “reprobate” is probably too esoteric. Let me borrow one instead from the middle-aged Elmore Leonard fan whom Gordon encounters in the State Library Victoria early in the book: “dickhead”.

Yes, that about captures it: the protagonist of Excitable Boy is an unequivocal, grade-A dickhead.

Fortunately for Gordon (and dickheads more generally), the affliction may be chronic, but it need not be terminal. And as a host of reformed dickheads – from Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Thomas De Quincey to Luke Carman – have proven, there is no panacea more effective, or alluring, than creative nonfiction.

Read more: Luke Carman, the circle of life, and the world as an ecstatic masterpiece

As the book’s title suggests, the essays have been brought together under the theme of risk. This denotes an overriding structure or cohesion that I felt somewhat lacking from the work as a whole. The essays are quite repetitive on certain issues, for example, indicating the idea of a collection came quite late in the writing process.

But it is an appropriate enough umbrella topic, given the protagonist’s penchant for putting himself in harm’s way. While some of this behaviour comes across on the page as a little tiresome (tagging train carriages with his black graffiti marker or doing drugs yet again), there are moments that succeed in making good on the shock that the title page seems to promise.

Take the episode in which the 15-year-old Dominic loses his virginity after a course of hormone treatment taken to combat late-onset puberty:

Around the time of the injections, we moved from Footscray to an apartment in Balaclava. One night I was riding my bike home from a friend’s house, through the park, and I saw half a dozen guys appear from the shrubs … I slowed down to see what was going on … literally a second later, a middle-aged guy with a tan and no pants on, emerged from some shrubs right near me. I wasn’t gay, but that didn’t seem to stop me … He walked right up to me with a condom in his hand and told me to fuck him … I put my bike down, went back into the shrub and fucked him.

There may be a corner of the city in which this passes for a healthy sexual awakening, but I found it truly disconcerting – all the more for the detached tenor of the retelling.

Detachment characterises much of Gordon’s storytelling as he kicks his younger self around the back alleys of Melbourne like a half-squashed can of Monster Energy Drink. It is never quite clear what the root cause of his disaffection is exactly, but it causes a deep cynicism toward systems of authority and other rigid social structures – like narrative.

To be honest, I still haven’t made my mind up if Gordon’s aversion to Aristotelian catharsis is one of the book’s virtues or vices. Christos Tsiolkas, who provides an introduction, calls this style of writing “raw”. But is it raw like punk music, or is it raw like a chicken kebab purchased from the takeaway joint two doors down from the punk bar where some unit just got his face smashed open with a schooner glass while waiting in line at the trough? Good raw or not-so-good raw?

Gordon appears well-aware of the fine line he is straddling here. In an essay titled Graff: The Writer’s Reality (“graff” is short for “graffiti”, in case you’re unhip enough to be wondering), he observes:

We made it! But made what? Back then, I didn’t have a clue why I really did what I did. That level of self-awareness wasn’t available, and even today it’s blurry.

Blurry is an appropriate description of the level of self-reflection Gordon grants his narrator. He is a figure capable of recounting key events from his life with impressive precision, but he has no time, patience or interest in meditating upon these events – and certainly no interest in learning from them.

In creative writing parlance, he is what you would call a shower, not a teller. In teenage delinquent parlance, he is a hectic risktaker, not a thinker.

Ultimately, I felt the book struggled a little with all its unmediated detail. Flannery O’Connor diagnosed this syndrome more than half a century ago when she declared (albeit in relation to fiction):

Fiction writers who are not concerned with concrete details are guilty of what Henry James called “weak specification” … However, to say that fiction proceeds by the use of detail does not mean the simple, mechanical piling up of detail. Detail has to be controlled by some overall purpose, and every detail has to be put to work for you. Art is selective.

It is often difficult to gauge what overall purpose the details are serving in these essays, beyond fidelity to memory. This may be the way the author intended it – “Author note: many names have been changed in this book but nothing else, because it all happened” [my italics] – but a tougher edit would have served the collection as a whole by allowing the more poignant details to shine through.