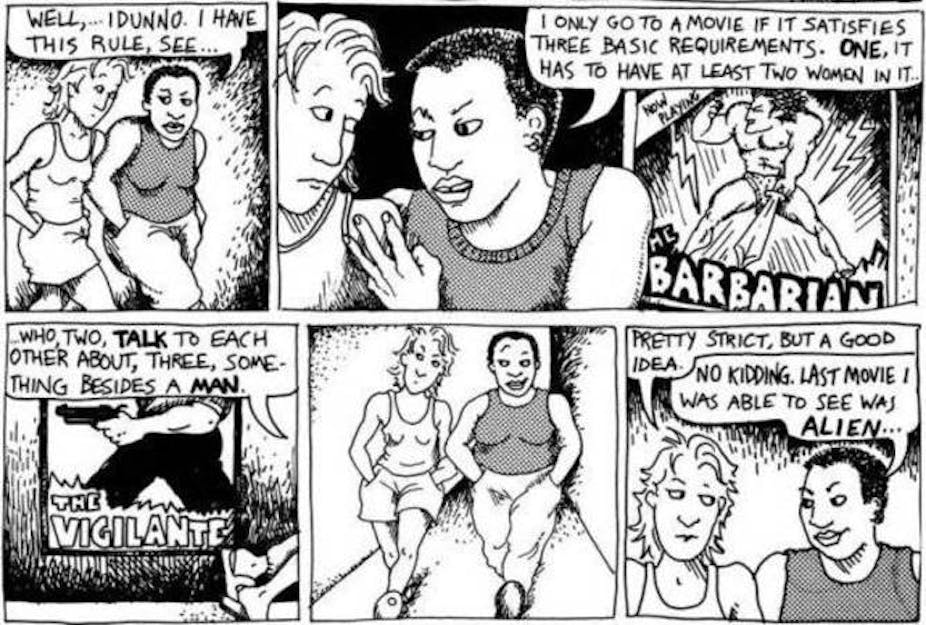

Four cinemas in Sweden recently pledged to rate films based on whether they pass what is known as the “Bechdel test,” a means of evaluating gender bias in film, named after American graphic artist Alison Bechdel. Only films that pass the test will be given an “A rating”.

The rules for the test, modelled on a comic strip from 1985 (see above), are as follows:

The film has to have at least two women in it.

-

The two women must talk to each other.

They must talk about something besides a man.

While it might not seem too hard to meet these criteria, at the time of writing, only around half of the 4,537 films surveyed in this online database obey all three of the rules.

There are a number of surprising fails, like Run Lola Run, even with its compelling female lead; and more complicated fails, like The Hurt Locker, helmed by the first female winner of the Best Director Oscar, but only involving one female character.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 and the entire Lord of the Rings series also fail the test (both films have two or more women in them but they do not speak to each other).

Many pundits have spoken in support of the test in the past, and now there are many voices getting behind its implementation in theatres.

But there are also those who have challenged the new Scandinavian approach, and some who critique the limitations of the test itself.

There is nothing wrong with wanting to correct the gender imbalance on our screens, especially if doing so were as simple as including a scene of two women discussing the weather.

And yet, by concerning ourselves with surface appearances, we run the risk of overlooking some of the most problematic (and fascinating) prospects of film as a medium.

Scratching the surface

The major issue with the Bechdel test is that it only demands small modifications to the narrative events in the movies we watch, and doesn’t ask for any deep, structural changes.

Ultimately, the test ends up telling us that the content of a film is more important than its form; that is to say, we are being told that what is most important about women on screen is simply what they do, not how they are shown to do it.

We need to start thinking more deeply about how films are shot and edited, and what those choices do to make us think differently about women in cinema.

If the absence of female characters is cause for concern, we should also consider how the cameras in big budget films tend to frame female bodies in an overtly sexualised fashion.

More often than we’d care to admit, the Hollywood camera not only follows the eyes of male characters in deciding what to focus on, but it routinely keys us into a male perspective, constraining us to view women on screen in a very particular manner.

The following scene from the 2007 film Transformers should serve to demonstrate the point:

And, lo and behold, Transformers actually passes the test!

But if this (very obvious) example reveals only the negative aspects of film form for women, then what of cinema’s ability to represent female characters in a more flattering light?

In the stunning prologue to the 2011 film Melancholia, Danish director Lars von Trier creates a long, wordless montage that draws comparisons between the niggling depression of the film’s female lead, Justine (Kirsten Dunst), and nothing less than the end of the world:

In this film, the series of conversations between Justine, her sister, and her mother, are all fairly muddled and inconsequential.

Instead, it is set-pieces like the one above that offer the lasting images of the film, and help us to understand something about those otherwise strange female relationships.

The form of a film can serve in other ways to make us rethink the power of women on screen. Even when a director chooses to show a female character in absolute isolation – and hence not roadworthy for those few Swedish cinemas – there is often something very powerful in showing just how powerless she is.

In US director Jeff Nichols’ fantastic Mud (2013), we see Reese Witherspoon locked inside a motel room for most of the film, in which almost all of her lines revolve around one man – namely Matthew McConaughey.

In this case, Witherspoon’s character never comes into contact with other women, but it’s precisely this lack of female community, and her attachment to male friends and foes, that makes her character at the same time complicated, pitiable, and infuriating.

Alien – the gold standard?

Bechdel’s original comic strip ends on an interesting note. For the cartoon character speaking, the last movie that passed the test (circa 1985) was Ridley Scott’s Alien. In that film, Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and the other female crew-member, Lambert (Veronica Cartwright), discuss the film’s monster (thereby passing the Bechdel test).

But for those of us who know the film, we will also know that it is not dialogue, but the lack of dialogue that makes Alien such a haunting experience. Indeed, who really remembers the words that pass between Ripley and Lambert on board the Nostromo?

Feminist film critics have been far more interested in how we interpret the final scene, in which Ripley – the lead character and sole survivor – is reduced to her underwear.

In these last shots, the camera, which until now has moved in such a fascinating way through the corridors of the ship, seems to revert to old Hollywood habits, embarrassingly ogling Weaver’s body (or does it?)

The Bechdel test doesn’t speak to a question of film form like this one, and so by following it to the letter, we would miss a good deal of cinema’s political significance.

It is questions like these, rather than those of the test, that filmmakers need to start answering first.