It is somewhat alarming when a media law academic finds himself on the wrong side of a media law. But that is exactly what happened to me when I discovered the new edition of our textbook was in breach of a suppression order on the name of Adrian Bayley – the man who murdered Jill Meagher.

Our experience highlights serious problems with the system of suppression orders in the courts today as they try to grapple with the ever-increasing challenge of keeping internet-savvy jurors from having access to reports of the past trials or convictions of the accused.

Victorian County Court judge Sue Pullen issued the suppression order against anyone publishing “any information relating to previous convictions, sentences, or previous criminal cases of the accused”. The orders were lifted on Thursday after Bayley was convicted of raping three other women before he raped and murdered Meagher in September 2012.

Easy to be in the dark about an unreported order

On one view, Pullen’s orders constituted a “super injunction” because they suppressed mention of the proceedings – and therefore of the suppression order itself. Perhaps understandably, news of the order had not spread beyond the inner circle of lawyers and mainstream court reporters and editors, mainly in Victoria.

The suppression order only came to my knowledge as a Queensland-based academic when I happened to be sitting on a conference panel in Melbourne with a media lawyer and a judge last year discussing the futility of suppression orders in the modern era.

The media lawyer told the audience of court officers, lawyers, journalists and academics that he had recently appeared in court several times to try to have this particular suppression order overturned – without success. He said he could not be specific about the suppressed identity of the accused (wisely, as representatives of that court were sitting in the audience).

But when he mentioned the notorious crime itself my heart skipped a beat. It dawned on me that our new edition of The Journalist’s Guide to Media Law, which was sitting in the publisher’s warehouse awaiting distribution, was in clear breach of the order. Bayley had been named and linked to the Meagher murder on three pages of the book. He also appeared in its index.

I hate to think what might have happened if I had not been at that seminar. I do not know how we could possibly have known of the existence of this suppression order other than by word of mouth.

Contempt of court risks heavy penalties

When I notified the publisher they took legal advice and paid to have the edition reprinted – with Bayley’s name deleted – in just enough time to have the new stock in university bookshops for the start of the 2015 academic year. Review copies were despatched to books editors and academics with the suppressed material manually redacted with a black felt pen. These remedial measures were taken at considerable cost to the publisher.

All this was done despite a prospective juror never being likely to view a few pages of a small-circulation university textbook. It was therefore extremely unlikely the book could ever have prejudiced Bayley’s new trials. That means its publication would never have constituted contempt of the sub judice variety – publishing material that would stand a real risk of prejudice to a trial, “as a matter of practical reality”.

However, there was a risk that it would nevertheless have amounted to the “disobedience” variety of contempt – disobeying a suppression order. The small circulation of the book would not have been a defence to that offence.

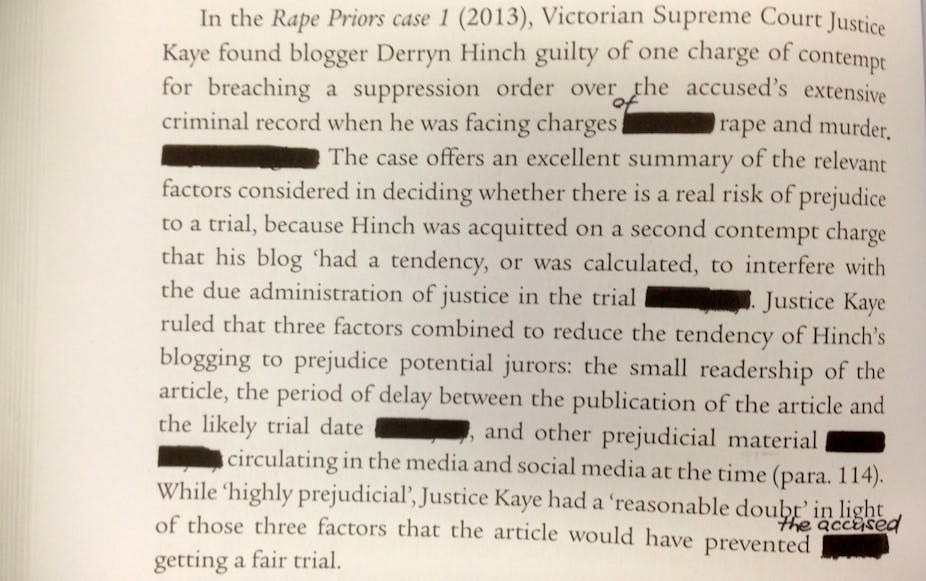

The irony was that Bayley’s name was mentioned only in our explanation of the breach of an earlier suppression order on his criminal history by broadcaster and blogger Derryn Hinch. We explained that Hinch had been jailed in 2014 for refusing to pay a A$100,000 fine for mentioning Bayley’s prior convictions on his Human Headline blog on the eve of the Meagher rape and murder trial.

The court found Hinch was not guilty of contempt for prejudicial publication (sub judice), because his blog had not reached a large enough audience to prejudice the proceedings. But he had breached the suppression order, which was a simple matter of disobedience.

We faced the same fate.

Social media reveal gaps in law’s reach

Our narrow escape underscores serious problems with suppression orders. Despite lobbying by media for many years, there is no national notification system for such orders. As a result, news media and other publishers in different jurisdictions are unlikely to know about such orders unless they inquire.

It is hard to inquire about a suppression order you do not know exists because discussion of its existence and contents has been suppressed.

This also highlights the impossibility of courts suppressing details about the accused in high-profile cases when these are being broadly published by ordinary citizens on social media. These postings are often beyond the reach of any court suppressing the details.

Further, in notorious cases, a simple internet search reveals numerous mainstream media items in breach. These were published prior to the issue of the order and, being online, would be hard to remove completely even if a so-called “take down” notice were issued.

Australia has a two-level system of suppression order enforcement. At one level are mainstream media. These media outlets are hog-tied by the orders because they are high-profile, easily identified, commercial targets reaching large audiences and therefore likely to be prosecuted for breaches.

At the other level are the broader social media citizenry. Their individual posts might not stand to damage a trial. However, their combined efforts on Facebook and Twitter offer a potential juror an array of circumstantial material about a high-profile accused along with a clear assumption of their guilt.

A way forward

Our multi-university research team considered this issue in a report commissioned by the Victorian Department of Justice on behalf of the then Standing Council on Law and Justice in 2013.

We recommended better directions to jurors and training of jurors. In part, this might alleviate potential prejudice against a notorious accused being pilloried on social media by educating jurors about basic principles such as the need to consider only what has been presented as evidence in a trial and that prior charges and convictions are not an indication of guilt in the matter at hand.

That was, apparently, the course of action adopted in these recent Bayley trials. The jurors were made aware of the notorious accused’s history and were told to limit their deliberations to the evidence in the case at hand. But surely the principle of open justice moots against the continuation of a suppression order on the linking of an accused with his notorious past once the jury has been told to ignore it.

At least there has been a positive outcome of this experience. The episode makes an engaging case study for my media law students as they learn about suppression orders and the need for reform.