On 7 April 2014, Rwanda commemorates the 20th anniversary of the genocide against the Tutsi. The events of 1994 continue to cast a long shadow over both Rwanda and the international community. As the world remembers along with Rwanda, it is important to reflect not only on the lessons and legacies of the genocide itself, but also the role of Western donors in supporting Rwanda’s transition to a peaceful and more prosperous future.

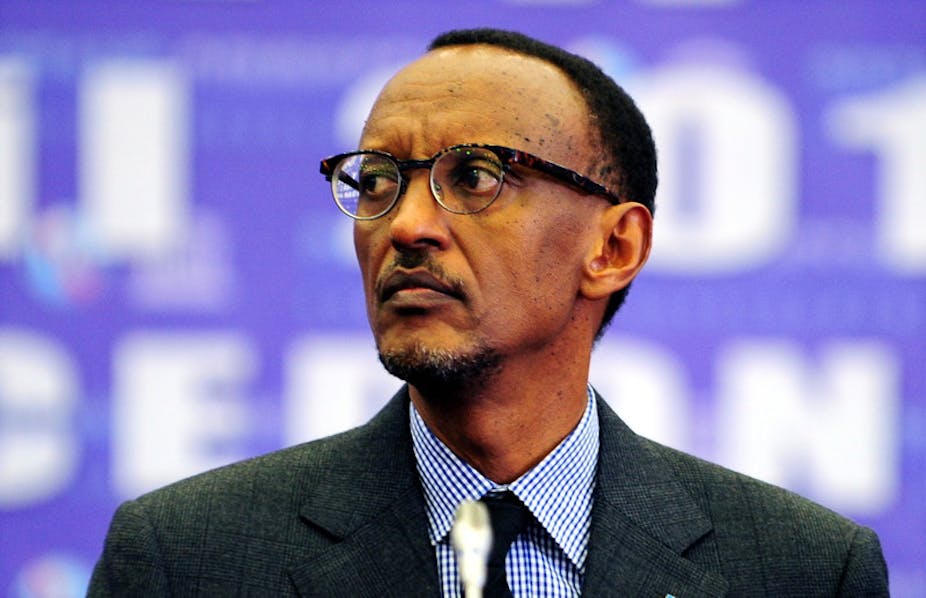

Spring 1994 saw more than 800,000 Rwandans, mostly from the ethnic Tutsi minority, killed in a genocide planned by a Hutu-led Government and carried out by armed forces, Hutu militia and ordinary Rwandan Hutus. The genocide was ended by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group made up primarily of Tutsi refugees and led by Paul Kagame. It left Rwandans divided and shattered, with more than 100,000 people in overcrowded prisons, and created a refugee crisis. Although most refugees have since returned home, its legacy remains in the form of anti-Tutsi militia in DR Congo.

At the international level, the genocide demanded better responses to state violence against civilians, and catalysed programmes to build African forces to manage crises on the continent. Guilt over their inaction led Western donors to fund Rwanda’s development, with some impressive results. It also left them reluctant to criticise problematic aspects of Rwanda’s domestic and foreign policies. Two decades on, there are signs that Rwanda’s “genocide credit” is beginning to wane.

Onward and upward?

Given its post-genocide challenges, Rwanda’s overall progress has been remarkable. Many of its policies, however, remain deeply problematic. The genocide’s domestic and international impact has continued to shape Rwanda’s politics, development and foreign policy; it also still influences the ways the international community engage with Rwanda, and how it responds to conflict and crisis on the African continent at large.

The memory of 1994’s atrocities still resonates in calls for international help wherever states target their own people. The cry of “no more Rwandas” is often heard in relation to the current crisis in the Central African Republic) (CAR).

With Western states willing to help manage African conflicts by providing funds and equipment but rarely troops, “African Solutions to African Problems”, however underdeveloped, must fill the gap – and Rwanda has been at the forefront of these efforts.

It is currently the sixth-largest contributor of troops to UN peacekeeping missions, including in Darfur, South Sudan and CAR. The genocide made Rwanda’s government deeply wary of relying on external actors to protect civilians in Africa, and the country has been at the centre of debates on the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), its experience of genocide lending it substantial moral weight. Its seat on the UN Security Council in 2013-14 provided opportunities to promote this agenda.

However, its activities in Congo have caused some to accuse Rwanda of failing to live up to R2P itself. The post-genocide refugee crisis led Rwanda to intervene in Congo twice, forcing Hutu refugees to return and tackling militias threatening to “finish the genocide”. These groups persist, but are much diminished. A leaked UN report in 2010 accused Rwandan forces and groups working with them of committing war crimes against Hutu civilians during these operations – claims Rwanda denies.

In 2012 allegations around one such group, the M23, led Rwanda’s main donors to cut or suspend aid. This was the first concerted effort by donors to influence RPF policy in Congo and, with the M23 “defeated” in 2013, it seemed to have the desired effect.

Around half of Rwanda’s budget has come from aid donors in recent years, and it expects them to donate 40% of it in 2013-14. The country is seen as a good performer, able to demonstrate tangible results from foreign investment. It has made significant progress against the Millennium Development Goals, its growth averages over 6% per annum, and poverty and inequality have fallen.

The devastation of the 1994 genocide makes these advances all the more impressive, and there is little doubt that the lives and life chances of most ordinary Rwandans have improved under the RPF. But Rwanda’s achievements have occurred within a tightly controlled political space – and the dissent generated in response may threaten future stability.

One-party state

The RPF has dominated politics since the 1994 genocide, and places a strong emphasis on national unity. The government has sought to build a new Rwandan national identity which has no connection to ethnicity, outlawing ethnic discrimination and making the discussion of such identities taboo.

Instead, the rhetoric revolves around on consensus and popular participation; elections are held regularly, but there is little real alternative to the RPF. Kagame garnered over 90% of the vote in 2010, with his second and last Presidential term set to end in 2017.

High-profile opposition figures are essentially prevented from campaigning or standing; they are often accused of links to groups involved in genocide, or of the more nebulous crime of “genocide ideology”. This constricted political sphere has created an opposition in exile, and Rwanda’s methods of dealing with opponents have damaged its relationships with the other states hosting them, such as South Africa.

Following attacks on Rwandan opposition leaders there, culminating in the January 2014 murder of Patrick Karegeya, South Africa accused Rwanda of direct involvement, and expelled Rwandan diplomats. Kagame and other Rwandan officials have not taken responsibility for the attacks, but they also refuse to condemn them.

Rwanda’s activities in Congo, and the responses from its leaders to allegations that it targets dissidents overseas, greatly worry its donors. The 2012 aid cuts seemed to successfully change Kigali’s relationship with rebels in DR Congo. The same donors may now be more willing to use their leverage to influence Rwanda’s political development, not just its foreign policy. Recent reports that the US is considering further cuts in security assistance suggest genocide guilt and peacekeeping contributions no longer afford Rwanda’s leaders the same level of diplomatic insulation.

As the 20 year anniversary rolls around, Rwanda’s leaders will need to decide if the balance of limited space for opposition but progress in development can be maintained without aid – or whether, as Christian Aid suggested on the tenth anniversary a full decade ago, “It’s time to open up.”