Donald Trump may well be remembered as the president who cried “fake news.”

It started after the inauguration, when he used it to discredit stories about the size of the crowd at his inauguration. He hasn’t let up since, labeling any criticism and negative coverage as “fake.” Just in time for awards season, he rolled out his “Fake News Awards” and, in true Trumpian fashion, it appears he is convinced that he invented the term.

He didn’t. As a rhetorical strategy for eroding trust in the media, the term dates back to the end of the 19th century.

Then – as now – the term became shorthand for stories that would emerge from what we would now call the mainstream media. The only difference is that righteous muckrakers were usually the ones deploying the term. They had good reason: They sought to challenge the growing numbers of powerful newspapers that were concocting fake stories to either sell papers or advance the interests of their corporate benefactors.

Fakers look to earn a quick buck

After digging into the history of the term, I found that journalists used “fake” in the 19th century to warn American consumers about products proffered by patent medicine pushers, con artists and hucksters.

But I also found that just prior to the Spanish-American War in 1898, readers started getting warned about “fake news.” At the time, the newspapers of media magnate William Randolph Hearst started publishing made-up interviews and stories about invented battles.

These sensational clips were often picked up – or copied – by news gathering agencies and sold wholesale to newspapers. They cascaded throughout the media system because, at each point, publishers realized they could make money by reprinting the stories.

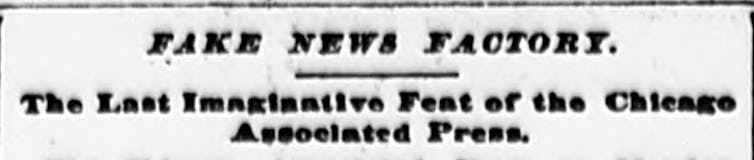

As the lucrative practice spread, critics started sounding the alarm. When the Associated Press manufactured and distributed a story about insurgents capturing Havana, The New York Sun took a whack at the AP, running the headline “FAKE NEWS FACTORY.”

In 1897, an article in The Minneapolis Journal also warned of “a fake news factory” near Duluth selling stories with a Midwest flavor for national wire service distribution. The article argued that each time a “fake news publisher” recirculated fakes, it became harder to tell what was true. At a certain point, “People cannot tell whether what they read has any foundation,” it said.

‘You’re the faker! No, you’re the faker!’

The effect of misinformation also drew the ire of the radical press, a growing number of periodicals that railed against the economic status quo. To these outlets, fake news was the pernicious effect of the profit motive on American journalism.

The radical press soon began using “fake news” as an epithet against established news outlets. The Milwaukee Social Democratic Herald, for example, decried syndicated fake news stories as “deliberate attempts to discredit the administration” of Milwaukee’s democratically elected Socialist mayor, Emil Seidel.

Populist William Jennings Bryan cried fake news when misleading stories went out over the AP wire claiming that Bryan was supporting Teddy Roosevelt for a third term. In The Commoner, the journal Bryan owned and edited, he wrote that “There seems to be an epidemic of fake news from the city of Lincoln, and it all comes from Mr. Bryan’s ‘friends’ – names not given.”

But just as crying fake news emerged as a technique to sow public doubt about the veracity of mainstream newspapers, establishment politicians used the ready-made defense to deflect the muckraking of the radical press. Long before Trump, plutocratic politicians were dismissing bad press by crying “fake news.”

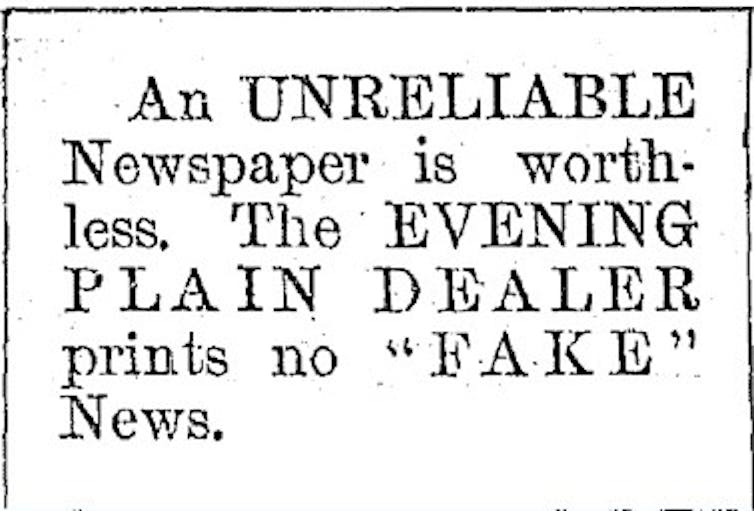

After The Evening Plain Dealer published an unflattering interview with Ohio Senator and GOP kingmaker Mark Hanna in 1897, he claimed it had been “faked.”

The Evening Plain Dealer defended “the absolute truth of every word of the interview, the utmost care is exercised in ascertaining facts, and no fake interviews or fake news are tolerated.” Just because someone called news “fake,” the editors warned, did not make it so:

“It is a common practice among public men to deny the accuracy of interviews which have proved to be boomerangs. They seem to think it an easy and justifiable method of getting out of an embarrassing situation, and are utterly regardless of the injury they may do reputable newspaper men.”

Hearst’s shameless New York Journal tried to muddy the waters more, championing the cause of unveiling fake stories to deflect criticism of its own made-up stories. Running a fake news bunco-steerer scheme to entrap rival Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World in 1898, it printed a fake dispatch about an artillery officer named Reflipe W. Thenuz – a rearranged version of “We pilfer the news.” The bait worked. For weeks, the Journal drove circulation by denouncing dozens of newspapers – not just The World – who fell for the con and had copied or reprinted the Journal’s fake news.

The power of corporate media

No matter how often radical periodicals denounced fake news published by their competitors, they found it difficult to suppress false information spread by powerful newswire companies like Hearst’s International News Service, the United Press Associations and the Associated Press.

These outlets fed articles to local papers, which reprinted them, fake or otherwise. Because people trusted their local newspapers, the veracity of the articles went unchallenged. It’s similar to what happens today on social media: People tend to reflexively believe what their friends post and share.

According to muckraker Upton Sinclair, syndicated “news” banked on this and knowingly spread fake news on behalf of the powerful interests that bought ads in their periodicals. Fake news was not only a sin of commission, but also one of omission: For-profit wire services would refuse to cover social issues, from labor protests to tainted meat, in ways that would depict their powerful patrons in a negative light.

Fake news was also used to manufacture public opinion.

“A certain state of public mind is often necessary,” journalist Max Sherover wrote in his 1914 book “Fakes in America Journalism,” for “the economic masters of this country to flimflam the people.”

Sherover explained how, if the Beef Trust wanted to raise their prices, their “publicity bureaus” would write up fake stories. They would then use their leverage to:

“… broadcast these stories throughout the land. The people that read the news get accustomed to the idea of the scarcity of beef. And when a few days later they are informed by the butcher that the price of beef has gone up they take it as a matter of course.”

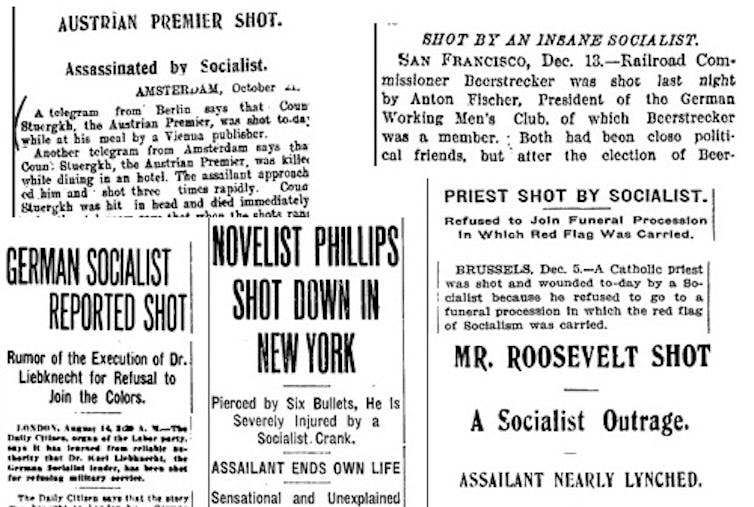

Meanwhile, groups critical of big business, especially socialists, were often targets of fake news. Whenever sensational crimes were committed, for-profit media would tie those crimes to socialists, adding phrases like “shot by socialist” before anything was known about the perpetrators.

Poisoning the well of truth

By the end of Gilded Age, the work of muckraking journalists who had exposed the sordid abuses of workers helped fuel recurring labor strikes. Yet just as frequently, news of these strikes were skillfully spun or suppressed in the mainstream media.

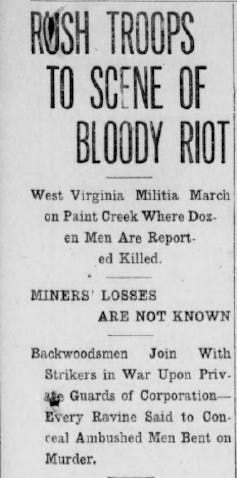

In 1912, coal miners in Colorado and West Virginia went on strike. Living in tent-colonies with their families, they were beaten and shot at by strike breakers and lawmen. For months, the AP was silent. The stories they eventually ran were anti-labor, including one fake claiming that miners had ambushed company guards, which justified sending in the troops to suppress them.

Sinclair would later prove that such stories had been fabricated by Baldwin-Felts strikebreakers or Rockefeller agents on the AP payroll. But by then, the damage had been done. Public opinion was formed – or, at the very least, muddied. Once again, the plutocracy got the fake news it paid for.

According to Max Eastman, the editor of the socialist magazine The Masses, the strike proved how dangerous the AP was, not only because it determined what was printed in a majority of the nation’s newspapers, but also because it feigned objectivity so fervently.

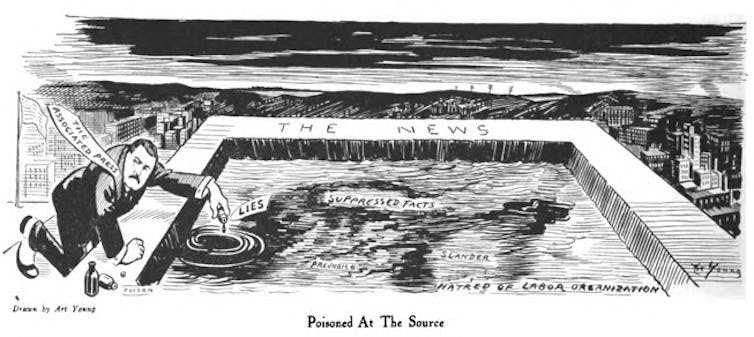

This “Truth Trust,” railed Eastman, held “the substance of current history in cold storage,” making it impossible for even the “free and intelligent to take the side of justice.” In the pages of The Masses, cartoonist Art Young depicted how the AP poisoned the well of truth with a potent mixture of “lies,” “suppressed facts” and “slander.”

To deflect these charges, the AP flexed its monopoly power. They could shut off service to newspapers that ran anti-AP news, so the views of Eastman and his sympathizers were silenced. AP lawyers actually pushed for and secured Eastman’s indictment for criminal libel – a feat, according to Sinclair, designed to smear reformers to the AP’s 30 million readers. When muckrakers reported on the scope of the AP’s fake news operation during the strikes in Colorado and West Virginia, the AP simply cried fake news and flooded the wires with sanctimonious defenses of their journalistic professionalism.

“If there is a clean thing in the US,” read one story distributed to millions of American readers, “it is the Associated Press.”

The Great War tips the scales

As World War I tore through the European continent, fake news flooded America’s media ecosystem. Newspapers ran sensationalist fakes targeting anti-war critics and fanning anti-German sentiment. Some of it was even furnished by German newswire services, reprinted unthinkingly for its sensational circulation value.

Just when an evidence-based debate about American war involvement was most needed, fake news poisoned the well.

After the U.S. entered the war, newspapers and journals that cried fake news about pro-war propaganda were censored by the state and pilloried by media syndicates that profited from war coverage; the decimated radical press lost ground.

Upton Sinclair saw the radical press’ collapse as a war casualty, one that foretold a crisis for democracy.

“The greatest peril in America today,” he wrote his own journal in 1918, “is a knavish press … pouring out the floods of falsehoods, like poisoned gas which blinds us and makes it impossible for us to see straight or to think straight.”

Without dissenting journalists pointing out fake news, he warned, “there is no way to get the truth to the people.” Short-lived cooperative news services struggled to compete with for-profit wire services. They had little chance in a media system that incentivized fake news.

Use of the term “fake news” has ebbed and flowed over the past. But it’s production has amplified over the past few years, as social media became the dominant means for news distribution. Once again fake news producers chased profit. Where there once there were fake news factories in Duluth, now we find them in Macedonia.

Trump may not have invented the term, but he’s deploying an all-too familiar tactic. Like the muckrakers, he cries fake news to erode confidence in the mainstream media; like Progressive Era politicians, he cries fake news when he gets bad press.

But these groups are different, because both fundamentally believed a vibrant press was crucial for America.

In his self-serving excess, Trump is more like Hearst, the don of news fakers, who knew that creating or condemning fake news drove news cycles and profits – damn the consequences.