In 1818, the young, wealthy, and fashionable British parliamentarian Richard William Meyler suffered a stroke while fox hunting. Meyler died intestate, and as a result, his extensive family estates in England and Jamaica were inherited by his closest male relative: his second cousin once removed, Richard Bright.

The ensuing legal battle between Richard Bright and branches of the Meyler family in Wales and Cheshire spanned five lawsuits and eleven years. The vast amount of documents outlining the familial and commercial relationship between the two families became known as the Bright Family Papers.

In 1918, almost exactly a century later, Richard Bright’s granddaughter Caroline died, leaving the family papers to her nephew Alfred Bright. Alfred was then living at Shipway Lodge in Sorrento, Victoria. His father Charles had emigrated to Australia in 1852 during the Victorian gold rush to establish a branch house of Gibbs, Bright & Co., a prominent colonial shipping agent and merchant.

In 1980, the Bright family donated the first of several batches of papers to the University of Melbourne Archives. The papers, with a full digital listing now available online, comprise more than 10,000 items. They include correspondence, accounts, inventories, maps, wills, and indentures, documenting 300 years of the Bright family’s public and private life. The earliest record, a will, was created in 1511. More recent material includes correspondence and family photos from the first half of the 20th century.

Many records were created in the Caribbean, where the Brights were sugar traders from the 1730s until the mid-19th century, when the emancipation of slaves led to a drastic drop in the profitability of their plantations.

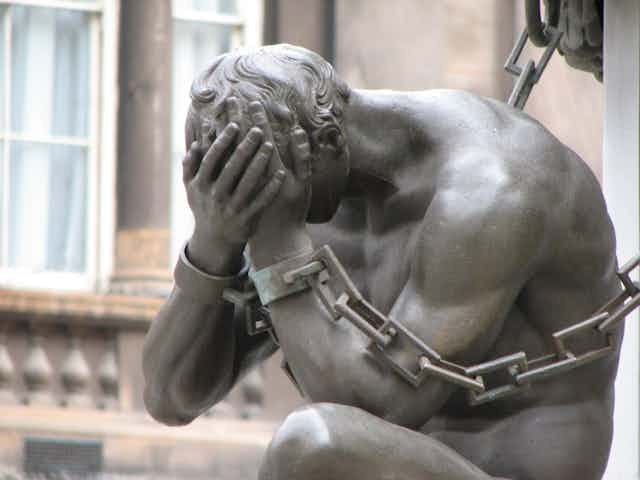

The insight the collection provides into slavery and the sugar trade is a disturbing reminder of the atrocious violations of basic human rights that funded colonial expansion. Inventories list slaves and their value alongside that of livestock and household goods.

The Brights purchased and managed sugar plantations and livestock pens, shipped cargo between Jamaica and Bristol, bought and shipped slaves, and established and ran stores trading in imported goods and sugar from local plantations.

The need to maintain constant contact with their commercial concerns meant a huge quantity of news, advice, inventories, and accounts was created and sent over this period. Many of the letters in this collection had already survived at least one transatlantic passage before finding their way to Australia.

The perils of sea

Perilous sea travel meant many letters were sent in duplicate or triplicate across successive packets, or were copied in at the end of the next letter.

The letters were written on both sides of large sheets of paper, folded into small rectangles, and sealed with red or black wax. The “envelope” was simply the outermost sheet of paper. Several of the letters sent in the 1840s still have their original Penny Black and Penny Brown stamps affixed.

The content of these letters is even more fascinating. They provide an immediate and disturbing insight into contemporary attitudes and realities of life in Jamaica.

One letter discusses Tacky’s Rebellion, a slave uprising involving Coromantee rebels near Savanna-la-Mar in 1760. Jeremiah Meyler, stationed in Savanna-la-Mar, writes to his business partner Henry Bright back home in Bristol:

On Whitsunday Captain Forrest’s Negroes rebell’d & killd Mr. Smith, his attorney, with others on the estate & in less time than 48 hours they were joined by Woodcock, George William’s, John Jones’s, part of Thomas Williams’s & Colin Campbells which made in number about 1,000. One hundred of them were armed. This you must concieve alarm’d the country, especially this part of it, in that every man in this parish were under arms for many nights & days, before any thing could be done to suppress these rebells.

I shall not pretend to give you a detail of circumstances, referring you to those that were on the spot, only to observe that the worst is now over & hope in a few weeks the tranquillity of the parish will again be restored, as there is not more than 300 Negroes now out, & few with arms.

Another letter from 1779 describes the Capture of St. Lucia, a West Indian battle in the Anglo-French War, reflecting that it had had no effect on the sugar price. A year later, in 1780, a hurricane hit Jamaica.

The devastation this caused to British settlements – and consequently finances – drew emphatic and emotive language from this anonymous writer, far more so than the wellbeing of slaves generally merited. The impact of weather and current events on crop prices was consistently the highest priority.

It is not just in transit that these documents faced danger. Storing paper and parchments for a long period of time requires vigilant attention to environmental conditions to prevent damage from damp and insects. In 1965, a fire destroyed Shipway Lodge in Sorrento, burning valuable paintings, including a Rembrandt.

Luckily, most of the documents in this collection were stored in metal deed boxes, shielding them from fire and water.

The earliest material consists of a will from 1511 and two arbitration disputes from 1532 and 1592. There are also numerous indentures from the mid to late seventeenth and early eighteenth century. The verso of one of these indentures, dated 9 January 1666, is illustrated with a perpetual calendar for the years 1699-1726.

Modern migrations

In 2016, nearly another century after making its way to Australia, the collection faces a further migration. This might be a figurative rather than a literal journey, but nevertheless the shift from print to digital is arguably even more consequential to the collection’s geographic reach.

After listing the entire collection and entering these into our archives database, we are now able to start digitising material, and making it available online.

Digital technology enables us to provide access to material like the Bright Family Papers to researchers around the world, but the collection’s provenance also offers a cautionary reminder for future generations of researchers and archivists.

The fixity and stability of print material enabled this collection to be formed over a number of centuries, from correspondence and legal and financial records that simply happened to be kept.

Pirates might not be scuttling the ships carrying digitised letters to our international researchers, but contemporary piracy and hackers pose a threat to the security of digital materials, particularly in online environments.

Fires and hurricanes don’t destroy digital information, but they can destroy storage hardware. Computer viruses replace the mould and silverfish which threatened collections in the past.